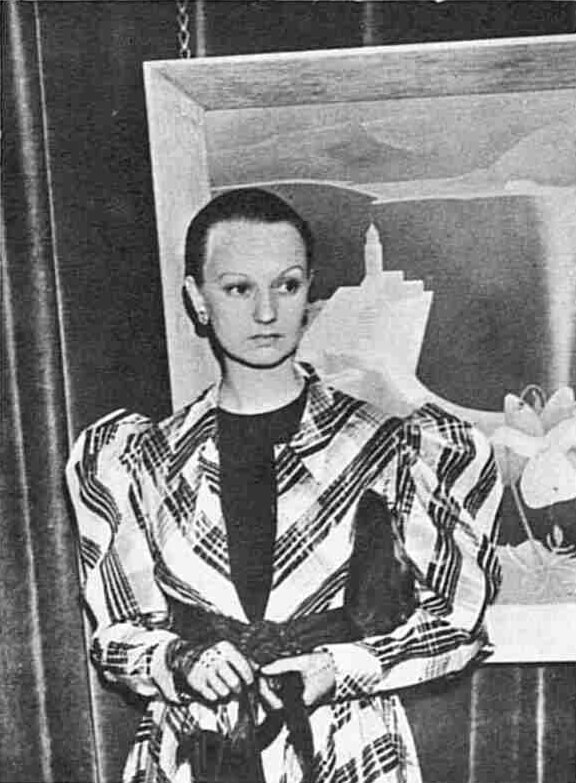

Ithell Colquhoun (1906 - 1988)

Ithell Colquhoun studied at Cheltenham Art School (1925 - 7) and the Slade School of Fine Art (1927 - 31), winning joint first prize in the 1929 Summer Composition Competition. After discovering Surrealism in Paris in 1932, she held her first solo exhibition at Cheltenham Art Gallery in 1936 and in 1939 joined the British Surrealist Group, showing alongside Roland Penrose at the Mayor Gallery that June. She was particularly interested in automatic painting and how it could unlock not just the unconscious mind but also the mystical.

Despite her expulsion from the British Surrealist Group in 1940 due to her increasing preoccupation with the occult, Colquhoun remained active in Surrealist circles; she was married to Toni del Renzio from 1943 - 48. She wrote and illustrated numerous books, including The Living Stones: Cornwall (1957), and exhibited in London at the Leicester Galleries and with the London Group, as well as in Regional galleries and abroad. She took part in several Surrealist retrospectives in the 1970s, including a solo show at the Newlyn Gallery in 1976, and the terms of her will bequeathed her studio (over 3000 works) to the National Trust, which in 2019 was transferred to Tate.