Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

This quote by Zanele Muholi (they/them) opens and succinctly frames their current show at the Tate Modern. The major exhibition presents the full breadth of the acclaimed photographer’s career to date, showcasing over 260 photographs that beautifully document, celebrate, and archive the lives of South Africa’s Black lesbian, gay, trans, queer and intersex communities. As a self-identified visual activist, Muholi raises awareness of social injustices, sharing personal experiences and stories from South Africa’s apartheid regime; they also make work responding to the discrimination based on race, gender, and sexuality that communities continue to face today. Through photography, they create positive visual histories and representations of under and misrepresented communities.

(See RAW’s 2023 article on Muholi’s show in the Maison Européenne de la Photographie,

Paris: https://r-a-w.net/blog/zanele-muholi-somnyama-ngonyama/)

Based on the artist’s 2020-21 show at Tate Modern, this exhibition additionally features new photographic and sculptural works, accompanied by musician Toya Delazy’s Zulu sound baths, which explore the possibilities of sound as a form of healing. The interplay of artistic forms scattered across the show creates an immersive space for viewers, inviting affective responses to the love, joy, pain, and healing depicted in Muholi’s photographs.

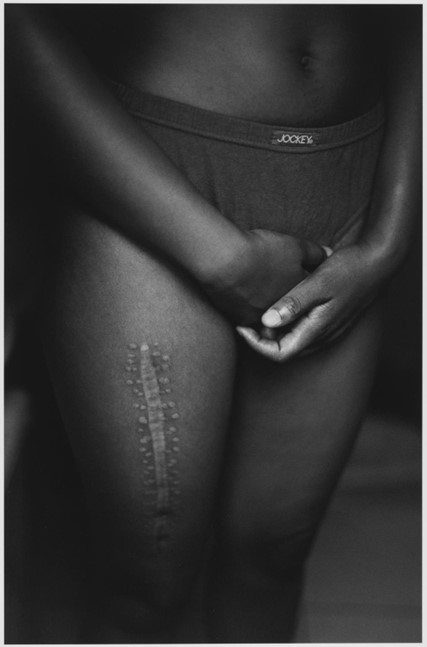

The first section, Only Half the Picture, is Muholi’s first series of photographs created between 2002 and 2006, as part of their work with the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, which they co-founded in 2002. Archival material – magazine articles, documents, and photographs – is displayed alongside Muholi’s work, speaking to their extensive activist involvement. This project “documents survivors of hate crimes living across South Africa and its townships. During apartheid, the government established townships as residential areas for those they had evicted from places designated as ‘white only’. Muholi presents the people they photograph – their participants – with compassion, dignity and courage in the face of ongoing discrimination. The series also includes images of intimacy, expanding the narrative beyond victimhood. Muholi reveals the pain, love and defiance that exist within the BlackLGBTQIA+ community in South Africa”. Muholi takes extra care to conceal the identity of its participants, representing them with great sensitivity, care, and dignity. The various close-up shots of participants in black-and-white – displaying their thighs, legs, chest, genitals – are not reductive renderings of individuals, but rather powerful acknowledgements of their experiences.

The second space features Faces and Phases, an ongoing series of portraits that Muholi started in 2006. With over 600 works in the collection, the project presents a collective portraiture that celebrates, commemorates, and archives the lives of Black lesbians, transgender and gender non-conforming people. “Many of these portraits are the result of long and sustained relationships and collaboration. Muholi often returns to photograph the same person over time. In the title, ‘Faces’ refers to the person being photographed. ‘Phases’ signifies a transition from one stage of sexuality or gender expression and identity to another. It also marks the changes in the participants’ daily lives, including ageing, education, work and marriage. The gaps in the grid indicate individuals that are no longer present in the project or a portrait yet to be taken.” Covering the walls of the exhibition space, Muholi’s portraits solemnly speak to the importance of documenting, showing, and representing Black LGBTQIA+ lives, in both cultural institutions and society at large. The exploration of time is an important element of this project, as Muholi dedicates their craft to the evolution, growth, and change of individuals over 18 years (and counting). In a context where representations of LGBTQIA+ communities often fail to present a futurity for its individuals, as depictions of lives are often characterised by threats of violence, disease, or ostracization; Muholi’s project offers a shelter where time and space are afforded to their participants.

Next, Being, Muholi’s 2006 series, captures ongoing moments of intimacy between LGBTQIA+ couples, as situated in the everyday, shared routines, and the private domestic sphere. The project is specifically grounded in the South African context, as “Muholi addresses the misconception that queer life is unAfrican or non-existent. This falsehood emerged in part from the belief that same-sex orientation was a colonial import to Africa. Same-sex relationships and gender fluidity have always existed in Africa.” Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg (2007) are 4 photographs in this series depicting a gentle, tender, and vulnerable lesbian love, manifested in simple states of bathing, kissing, and togetherness. Muholi explains how “lovers and friends consented to participate in the project, willing to bare and express their love for each other”; Commenting on this series, they say: “My photography is never about lesbian nudity. It is about portraits of lesbians who happen to be in the nude.”

In the same room stands Ncinda (2023), a bronze sculpture by Muholi, that depicts the full anatomy of the clitoris. “Ncinda is an isiZulu word that translates as ‘doing with the hands’; or ‘squeezing’. The sculpture celebrates the full anatomy of the clitoris, expanding on the visualisation of sexual pleasure and freedom that is central to Muholi’s work. Its scale and robust material give the form the appearance of strength and power, repositioning female genitalia after centuries of taboo, shame and violence.” The sculpture’s spatial presence amplifies the celebratory message of lesbian love in Muholi’s photograph series.

Transitioning from private spaces of desire, the fourth section Queering Public Space presents portraits of LGBTQIA+ participants in public spaces. These photographs make significant references to the historical, cultural, and political context of South Africa. In the same room, an archive and timeline of South African histories of activism, as they relate to apartheid and the emergence of queer activism, provide insight into Muholi’s life and work. The local specificity of Muholi’s work is clear. “Several of the locations have important historical meaning in South Africa. Muholi captured some images at Constitution Hill, the seat of the Constitutional Court of South Africa. It is a key place in relation to the country’s progression towards democracy. They photographed other participants on beaches. Segregated during apartheid, beaches are potent symbols of how racial segregation affected every aspect of life. Participants are often shown on Durban Beach, close to Muholi’s birthplace of Umlazi. Choosing to photograph participants in colour is a way for Muholi to bring the work closer to reality and to root them in the present day.” For instance, a photo from Muholi’s series Brave Beauties (2014 – ongoing), Durban Beach shows a group of trans women, gender non-conforming and non-binary people in the notable location, in defiant resistance of its history as a site of segregation during the apartheid period. The sheer scale of the photograph renders the vibrantly photographed beauties larger than life. Muholi’s work effectively “queers” both the public space of the beach as well as the gallery, advocating for LGBTQIA+ access and inclusion.

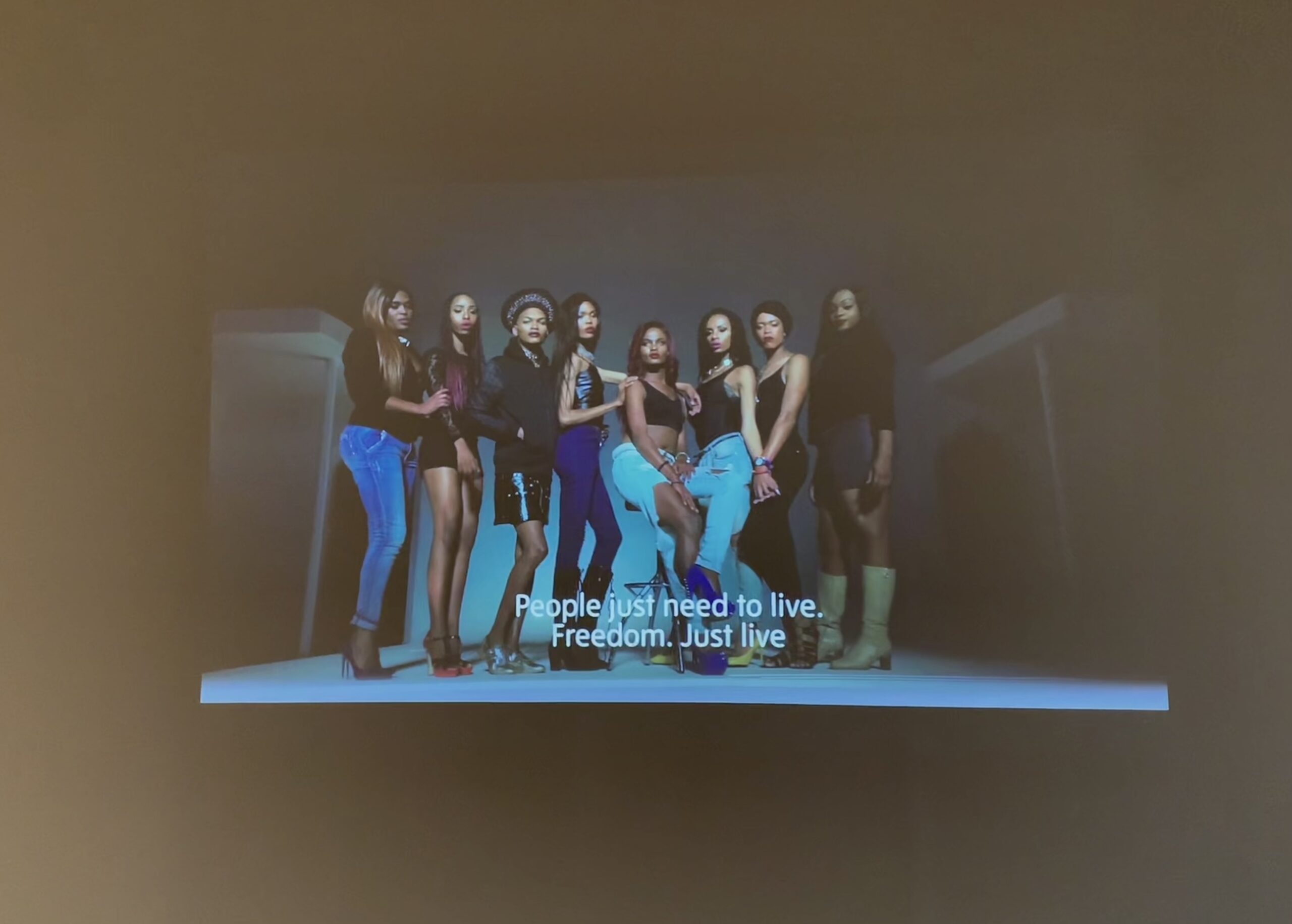

The fifth room delves into Muholi’s Brave Beauties. This series offers a glimpse into the queer beauty pageant scene, “a space of resistance for the Black LGBTOIA+ community in South Africa. They are a place where people can realise and express their beauty outside heteronormative and white supremacist norms. […] These images aim to challenge queerphobic and transphobic stereotypes and stigmas in the fashion industry. Muholi has questioned whether South Africa, as a democratic country would have an image of a trans woman on the cover of a magazine. As with all Muholi’s images, the portraits are created through a collaborative process. Muholi and the participant determine the location, clothing and pose together, focusing on producing images that are empowering for both the participant and the audience.“ Candice Nkosi, Durban (2020) for instance, pictures “Miss Gay RSA 2019/20″, clad in dangling earrings and an embellished crown, posing confidently and imbued with an air of regality. Muholi’s photographs spotlight queer beauty and effectively push back against conventional, heterosexual notions and ideals. Brave Beauties Public Service Announcement (2017, digital video, colour, sound) shows the beauties in motion, declaring: “We’re all born from love and I think that’s the one thing we tend to forget […] People just need to live. Freedom. Just life. Patience shall prevail.”

In “Johannesburg”, an artist segment with Art 21, Muholi expressed, “I work with people who are partaking in a historical project, who are informing many individuals, including me about their lives. So it’s very important for me that I respect the fact that they’ve trusted me enough to be there. I work with participants. There are no subjects in my photography.” Muholi’s dedication to their community and participants is consistent throughout their work – as an activist, their goal is not merely to represent individuals but rather to create spaces in which individuals can speak for themselves. Sharing Stories, the sixth section of the exhibition, showcases first-hand testimonials by Muholi’s participants, sharing their experiences as Black LGBTQIA+ people. “Giving participants a platform to tell their own story, in their own words, has been an enduring goal”. Muholi has said, “each and every person in the photos has a story to tell but many of us come from spaces in which most Black people never had that opportunity. If they had it at all, their voices were told by other people. Nobody can tell our story better than ourselves!”

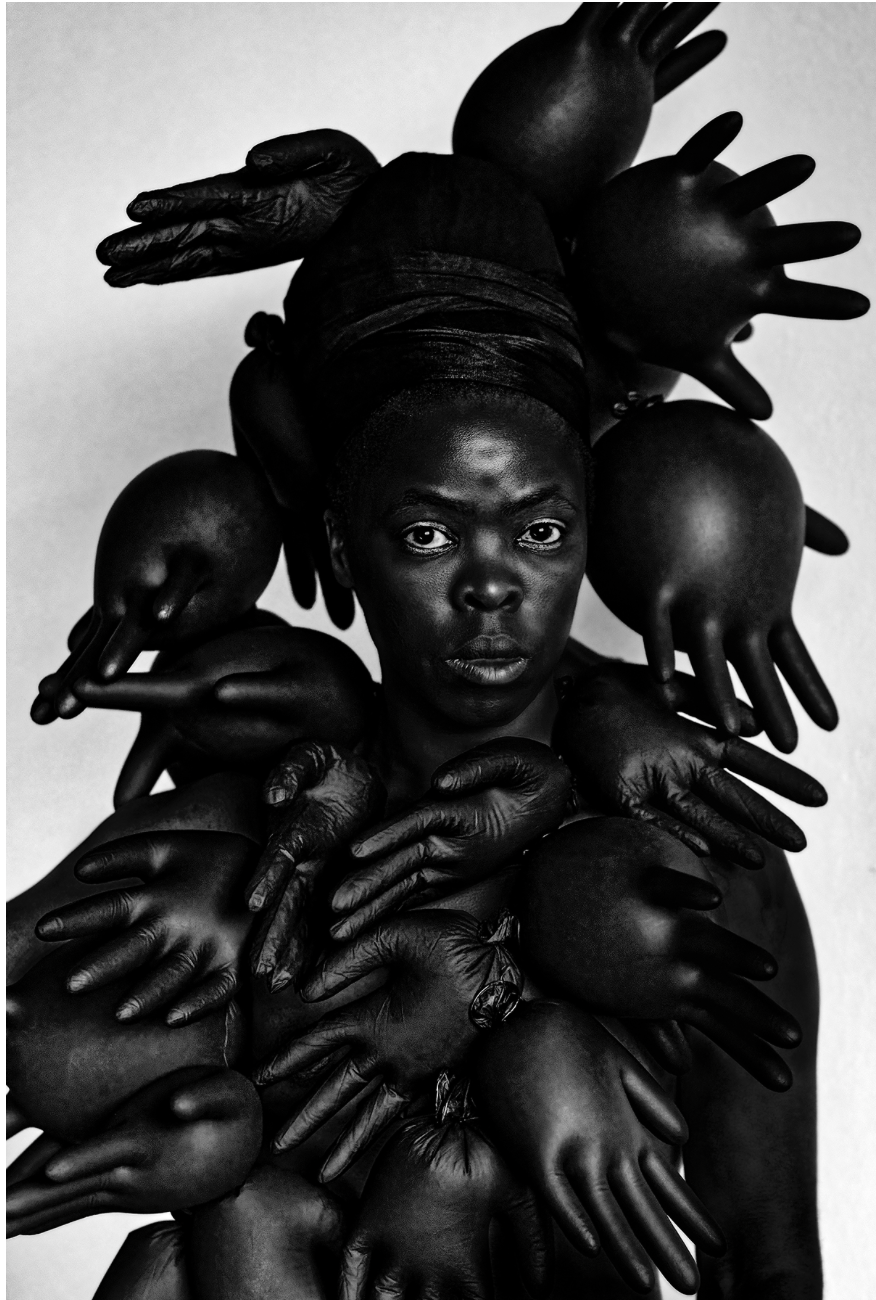

The seventh section features Somnyama Ngonyama (2012 – ongoing), Muholi’s renowned series of self-portraits that explores the politics of race and representation. Informed by both histories of oppression as well as Muholi’s personal stories surrounding family, self-identification, race, and gender, the portraits hold intricate narratives and challenge the silencing and marginalization of Black communities. Through their work, “Muholi considers how the gaze is constructed in their photographs. In some images, they look away. In others, they stare the camera down, asking what it means for a Black person to look back. When exhibited together, the portraits surround the viewer with a network of gazes. Muholi increases the contrast of the images in this series, which has the effect of darkening their skin tone. I’m reclaiming my Blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged others”. In this series, Muholi draws heavily on the symbolism and materiality of carefully chosen props, imbued with cultural, religious, and personal meaning. In Phila I, Parktown (2016), for instance, Muholi uses inflated gloves – alluding to those used in medical practice or crime scenes. “The abundance of inflated gloves surrounding and covering my body also speaks to the question of access – in particular the lack of access to dental damns or other forms of protections against STIs.” The gloves in the image form a physical barrier around Muholi; the black, air-filled vessels become one with Muholi’s body, expanding their form. Protection, in this piece, is imagined through an affordance of space for the photographed subject.

Other notable portraits in the collection include Manzi I, West Coast, Capetown (2022). “In this work, Muholi invokes the healing power of water (amanzi in isiZulu). Partially submerged in a tidal pool on the beach in Cape Town, they gaze at the viewer with defiance and playfulness. While beaches were segregated during apartheid, Muholi now reclaims this space. Immersed in the liquid horizon, the presence of the body manifests solace and repair.” The ocean as a significant symbolic site, is once again invoked – this time by Muholi as both the photographer and the ‘photographed’. Stepping into the waters, they speak of a personal connection to the local context of South Africa, a participation in the reimagination and reclamation of the beach, as well as a proud presentation of their blackness and identity.

Mmotshola Metsi (The Water Bearer), The Brave II (2023) in the same room is a statue, wherein “Muholi depicts themselves as a mythical being carrying a vessel embellished with uteri. They appear to emerge from a body of water, an act associated with spiritual cleansing and rejuvenation. The uterus, a reproductive organ that has often been controlled and subjected to shame and violence, is reinscribed with honor.” The interplay between three-dimensional and two-dimensional portrait-making is compelling and demonstrates Muholi’s ability for storytelling across mediums and forms. Somnyama Ngonyama at large, in its exploration of Muholi across contexts, locations, and physical presentations, can also be understood as “a homage to the plurality and fluidity of the self. For Muholi, their use of the pronouns they/them goes beyond gender identity. It acknowledges their ancestors and the many facets of their identity: “There are those who came before me who make me.”

The last section Collectivity emphasises the principle at the heart of Muholi’s work—it presents documents, archives, and photographs of events “such as Pride marches and protests or private events such as marriages and funerals” made together by Muholi’s network of collaborators, Inkanyiso. “By recording the existence of the Black LGBTQIA+ community, they resist erasure. The images reveal the power of collective voices in protests and social justice movements. They also celebrate the moments of love, care and resistance that are at the centre of Muholi’s community and activist work”. Overall, Muholi’s body of work places black bodies and lives at the centre, responding to social, cultural, and political contexts where they are often marginalised and hidden away. With each photograph, they tell important and redemptive stories of queerness, blackness, and collectivity in the face of societal discrimination, violence, and silencing.