Your currently viewing RAW Modern | Switch to RAW Contemporary

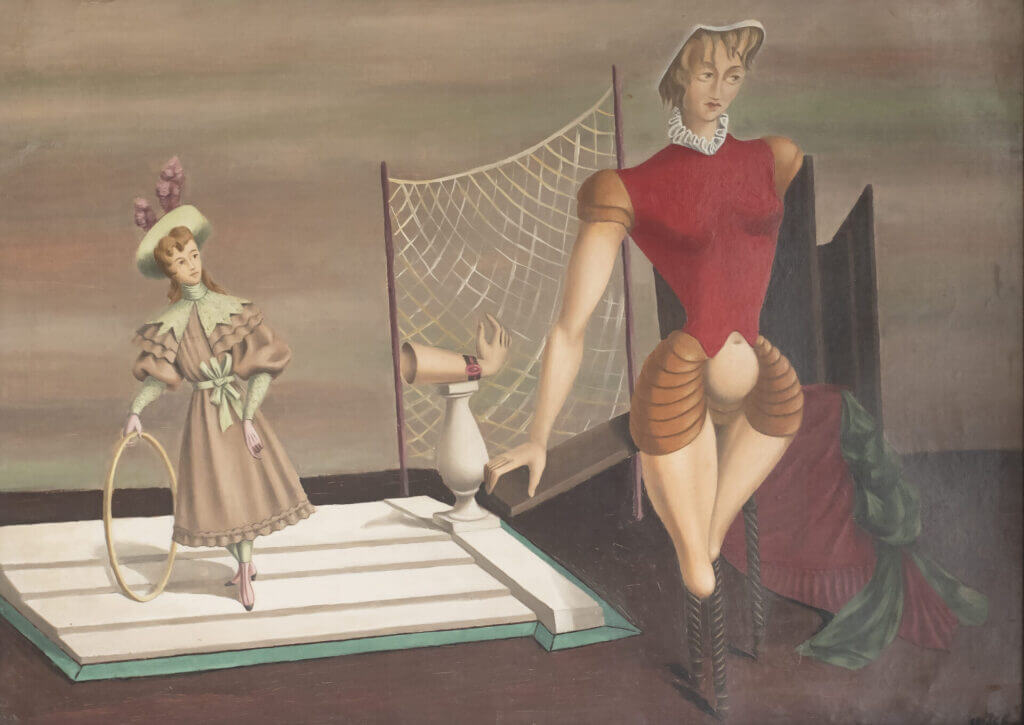

Le fil de la vierge, 1941

Catalogue essay by Blanche Llewellyn

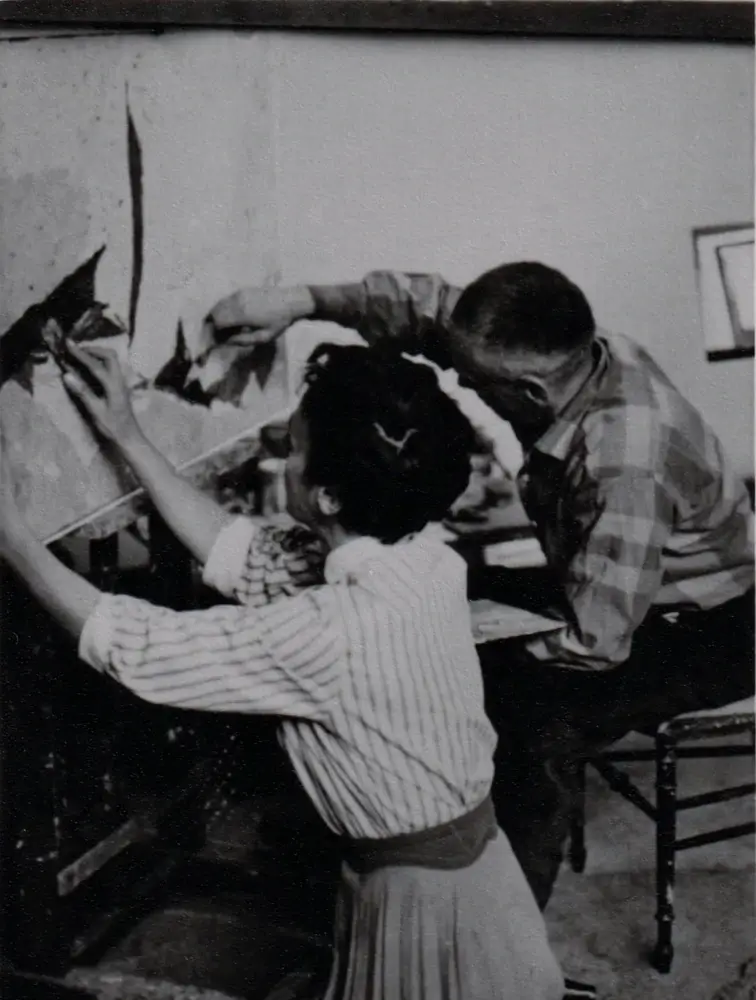

Seigle is the pseudonym of two artists, Henri Julien and Marie Nô Pin who worked side-by-side on their canvases. Seigle represented a new way of making art: the merging of two creative souls dreaming of freedom. Their surrealist phase extended from 1940 to 1952, and was highlighted by significant moments such as their invitation to exhibit at the Third International Surrealist Exhibition at the Galerie Charpentierin in 1964.

The couple left a lasting impression on the surrealist movement, especially on its leader, André Breton, who wrote about their work:

“To seize it in flight, I tell myself, doubtless requires more than the hand of a painter, a hand the likes of which has not yet been seen, a man’s hand indistinct from that of a woman, or better still, woman’s hand and man’s hand in one by virtue of a harmony that, taken once and for all so far as to entail a sole intention, requires a common expression. It seems to me that one could not insist enough on this exceptional warrant in human value for the art of Seigle: we have the chance to not only perceive the reactions of an individual sensibility, as rich as it may be before the “spectacle” of nature and its otherwise important symbolic implications, but also those of the couple who, by virtue of the fact that its elements have always lived side by side, sharing the same childhood impressions and shaped intellectually by the same education, has best approached a fusion of the senses.”

The title “Le fil de la vierge” refers to a French phrase “le fil de soi”: a spider’s web – of which the symbolism was so rich that surrealists often incorporated it into their artworks (Man Ray, Spider Woman (1948), Dora Maar, The Years Lie in Wait for you (1935) and later, famously, the motif of the spider and its web was extensively used by Louise Bourgeois).

In this landscape, the two figures seem caught up in a web of violence from which they can’t escape. The ambiance evokes the aftermath of World War I, delineating a clear before and after. On the left, a young girl seemingly portrays Marie Nô Pin herself, untouched by the ravages of war, resembling a Victorian paper doll. To her right, an androgynous figure exhibits both robust feminine and masculine traits. The figure, which has an exaggerated codpiece (a symbol of rampant masculinity) and a feminine torso, bears missing limbs —a poignant allusion to the wounded veterans of the Great War. The figure’s missing arm is delicately adorned with a bracelet, resting upon a Greek urn (heralding the end of classical civilization as we know it).

This image serves as a powerful anti-war statement, depicting a vision of hell characterized by a dualism between contrasting realities.