Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

“I decided that for the images to have magic qualities I had to work directly with nature. I had to go to the source of life, to mother earth”. – Ana Mendieta

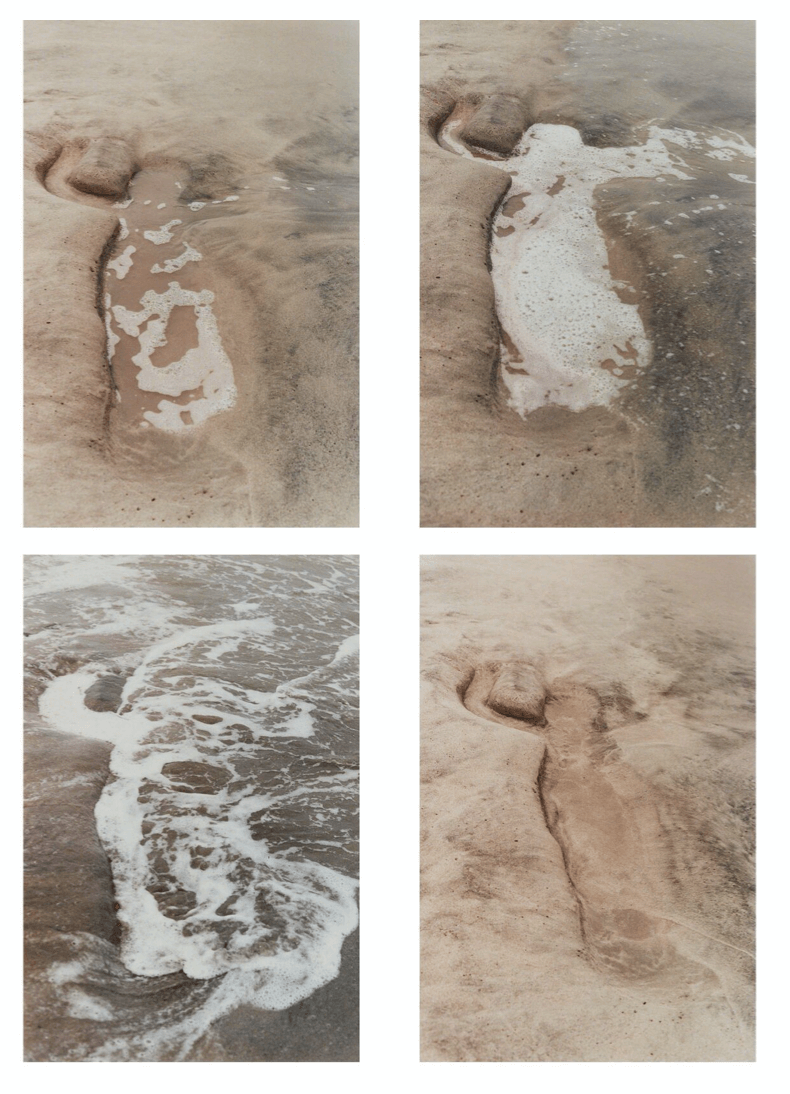

Ana Mendieta (born in Cuba, 1948) is perhaps best known for her Earthworks, a popular movement where art is created in nature by making site-specific forms in the land itself. A movement relatively dominated and defined by male sculptors – most notably Michael Heizer, Richard Long and Robert Smithson – is why Mendieta’s unique and spiritual. temporality to mark-making set her apart from her male counterparts at that time. For example, Heizer would leave his impression by adopting heavy, earth-moving machinery that would effectively carve up the earth to leave long-lasting alterations to the landscape. Mendieta, on the other hand, would temporally create her imprint in the ground using her body. She would then fill this cavity with a variety of natural materials, including herbs, grass, tree moss, mud, clay, hair, blood, gunpowder, and occasionally fire, to become one with the earth. The parallels between Ana Mendieta’s work and her untimely death are significant and remain hard to digest even to this day, almost four decades after that fatal fall on the 8 th of September 1985.

Her Sileutas series (1973-78) prolifically explores the ritualistic relationship between body and nature, where such subtle and temporary interventions to the landscape solely exist. by photographic and film recordings. We see her silhouettes are rooted in Goddess iconography and pay homage to her Cuban heritage, which is explored further with he Esculturas Rupestres series (1981), where she carved these silhouettes into the soft. limestone walls of the caves in Havana. As a young child, Mendieta was sent to the States as an asylum refugee, so these cave drawings and carvings are conceivably her attempts to evoke primitive female spirits to reconnect to her motherland.

The displacement and isolation she experienced in her formative years (feeling like an outsider growing up in the Midwest) indisputably shaped the artist that Mendieta would later become. Whilst a student at the University of Iowa, her earliest performance, Rape Scene (1972) was made in response to male violence by restaging the rape and murder scene of a fellow student. Here, we see Mendieta bent over a table, smeared with animal blood. It is interesting to note here that she used to collect blood from slaughterhouses, which coincidently has uncanny symbolic parallels to Mendieta’s tragic ‘fall.’ The devastating irony was that her mutated body would end up on the roof of a deli when she fell to her death from the window of their 34th-floor apartment in New York City on that fateful night. Considering Mendieta’s artwork had primarily been about the imprint her body left on the earth, the ritualistic and unsettling echoes of life imitating art are significant. The gendered implications are noteworthy too, which brings me to her tumultuous relationship with Carl Andre.

It was during her time in New York City that Mendieta became involved in the feminist performance art scene. She joined A.I.R. Gallery (Artists in Residency Inc) – which coincidentally was the first gallery for women in the States – and it was here that her self-named ‘earth-body’ works found an appropriate home, championing experimental and ephemeral artworks. It was also here that Mendieta met her future husband, Carl Andre in 1979, when the two visual artists were making a name for themselves within the American art scene. Not only for their work, where Mendieta was starting to be recognised in art circles, and Andre, already considered a ‘big deal’ with exhibited works in major galleries and museums since the late 60s – but for their drinking and fighting in public. Close friends observed that they both had strong and uncompromising personalities, and their romance was volatile and often in conflict. Despite this, they dated for several years before tying the knot in Rome in 1985.

Andre’s heavy, masculine sculptures differ greatly from Mendieta’s stylistic approach, where she would repeatedly turn her own body into an art object, making herself both image and medium. A popular feminist avant-garde performance trend in the 1970s, where Mendieta would animate the territorial boundaries between artist and audience, male and female, body and spirit. Andre’s sculptures and artistic personality were informed by his experiences with manual labour jobs, specifically as a railway conductor. It is interesting how both artists made their work inspired by their lived experiences, but the classic dualisms of Western thought have consequently shaped the marginalisation of women (and minorities in society) to the domestic sphere and as the ‘Other.’ This gendered public/private dichotomy enables the transcendence of the male, which generally and historically, has been at the expense of the feminine other. Considering Andre’s first solo-show retrospective at the Guggenheim was whilst he was 35 years old (a privilege rarely afforded to living artists, never mind at such a young age) speaks volumes in this case. With this in mind, the gendered connotations of the artwork both artists created cannot be overlooked, especially in the context of Mendieta’s death.

The night of Mendieta’s fatal fall, the couple were quarrelling about ideal love – after watching Without Love (1945), a depressing love story – Andre’s notoriety, and her lack of. In the early hours of the morning, Andre called 911 to report a suicide. The verbatim transcript reveals that he told the operator: “my wife is an artist, and I am an artist, and we quarrelled about the fact that I was more exposed to the public than she was. She went to the bedroom, and I went after her, and she went out of the window.” His detached and monotone delivery of the death of his wife echoes the coldness of his sculptures. This phone call was. aired in the courtroom to a juryless court where he was later acquitted of all charges – and went on to enjoy a hugely celebrated career amongst the art world elite. Despite the suspicious circumstances, Andre was absolved of all responsibility and why I have alluded to how the gendered implications are consequential. If considering the male/female division that has defined society (and the woman’s role), it is no surprise that Mendieta’s death happened in the domestic sphere, anchored to the feminine ‘Other.’ Much of second-wave feminism has been dedicated to the systemic and quotidian oppression of women in the domestic environment. It was characteristic of feminist artists at this time to work with their body and nature, where the lands offerings are vast and limitless. At this time, in the 1970s, female artists adopting goddess symbolism were looking to reclaim power and purpose in their societies that had Othered them. Mendieta’s fascination with the earth and Cuban cultural traditions created sculptures that were unmistakably human and why her mystical experimentation of Self and deconstruction of identity feel as relevant and ground- breaking as ever. Despite such a short (and dynamic) career, Mendieta’s work was enormously prolific and continues to inspire much feminist and political discourses. The ‘Where is Ana Mendieta?’ movement was primarily organised by the Women’s Action. Coalition back in 1992, marking a series of protests in her honour.

This first demonstration mobilised approximately 500 protesters outside the Guggenheim museum on the opening day of an exhibition where Carl Andre’s works were on display. This provoked outrage, and the protest was in repose to a variety of injustices: not just the exclusion of women from an art museum, but their persistent absence from a wide range of domains of power; not just the marginalisation of people of colour, symbolised by Ana Mendieta, but the seemingly institutional sanction of a judicial verdict that pronounced Andre innocent of having killed her. More recently, protesters gathered outside Tate Modern in 2016 chanting ‘Where is Ana Mendieta?’ proving her absence and legacy remains impactful to this day.