Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

I have been a fan of Alice Neel’s work for some time now. Her stark and unsettling figurative portraits – especially the uncompromising and provocative female nudes – have always excited me. Making feminist female erotica myself, it is not difficult to understand why this would be the case but seeing Neel’s portraits in the flesh at the Pompidou retrospective on a cold morning in early December, a complex set of emotions surfaced. I will acknowledge I had a limited understanding of her work prior to this show, which was staggering and so well-curated (despite the clumsy English translations), that covered so much of her artistic practice and life story that was riddled with so much trauma before she rose to some critical acclaim much later in her career, and more prominently after her death in 1984. Despite being long ignored during her lifetime, her artistic legacy is much celebrated today: she figures among the most striking painters of the 20th century of American art and feminist discourse.

It was her earlier works from the 1930s that surprised me. She was much more political than I anticipated, highlighting the injustices and inequality of American society by exploring death, sickness, poverty, violence, racial segregation and (homo)sexual discrimination. Her black-and-white ink drawings from this time were particularly potent, with her subjects ranging from young Puerto Rican boys with tuberculosis to poverty-stricken mothers with their children from Spanish Harlem. Her interest in exploring the darker underbelly of society heightens the social and political issues of the Great Depression and symbolises the bleak reality for those left behind.

At first, when confronted with these works, I was curious about her positionality. Being a white and seemingly wealthy woman, for she was linked to the Rothschilds and travelled often, I felt uncomfortable with the voyeuristic tone of a privileged perspective. However, these works were undeniably empathetic and formative in constructing her style of portraiture that is much more honest and real. The challenges underlying the work of this ‘independent woman’ was a significant focus of the Pompidou show. Experiencing the death of her daughter, followed by her second daughter being kidnapped and taken to Cuba by her father, she had a nervous breakdown and attempted suicide. Another lover cut up 300 of the artworks, and another lover left her after the birth of their son, Richard. It is troubling to learn of her struggle with unworthy and abusive partners – and perhaps makes her legacy all the more impressive when considering the hardship she faced.

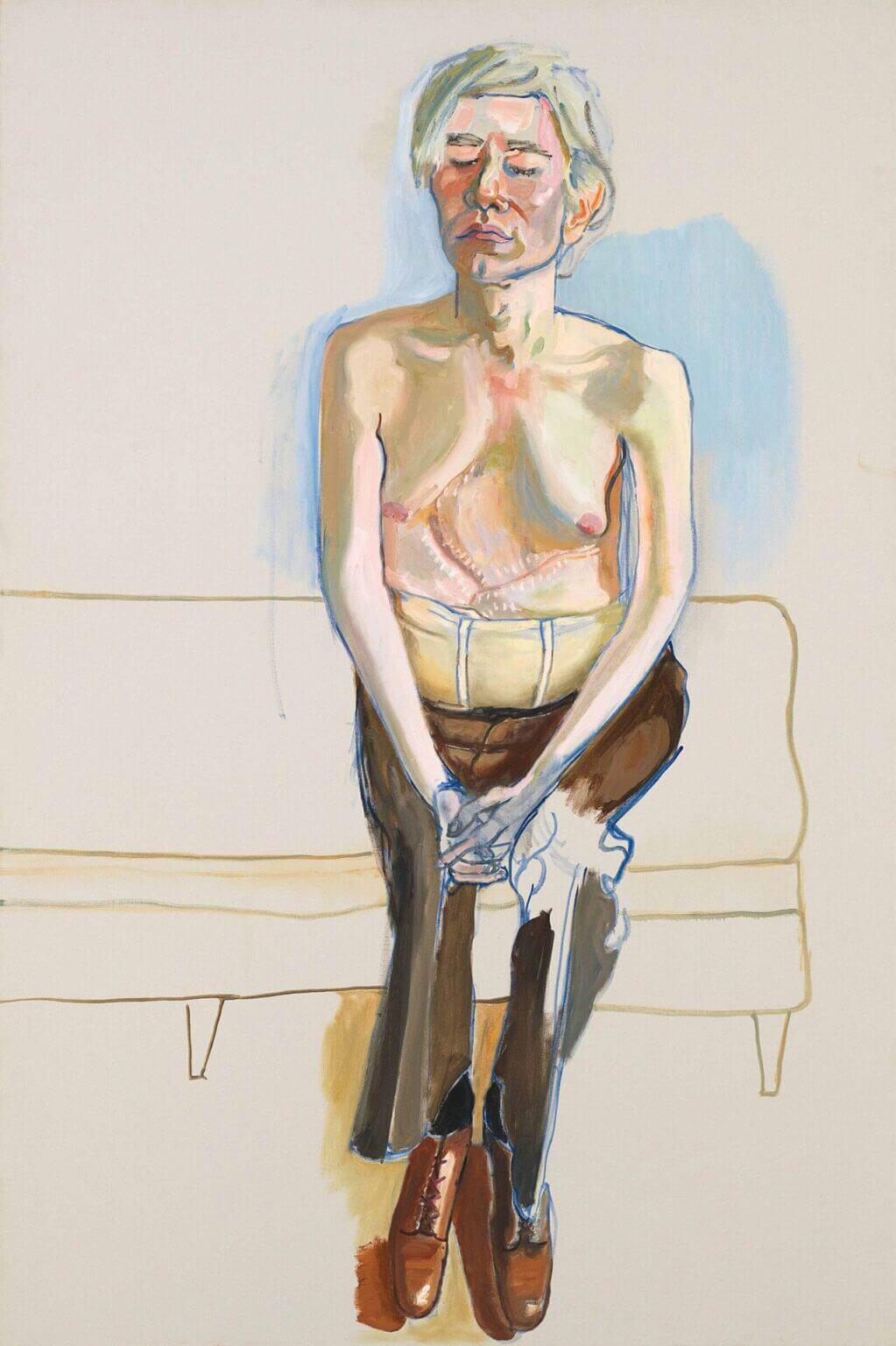

Neel’s work from the 1970s is the most emotive to me. Perhaps because of the influential sitters, such as the renowned artist Andy Warhol (1970), an enigma who was infamously known for his flamboyant attire and variety of guises in public, always adopted wigs, makeup, and above all, his sunglasses. In this portrait, not only is Warhol’s eyes closed and shirt removed, exposing his pale and scarred torse from when he was shot by Valerie Solanas (author of seminal S.C.U.M. Manifesto) a couple of years before sitting for this portrait. Neel’s use of colour is always so compelling, yet here, she uses a limited palette of cool hues to highlight Warhol’s fragility and vulnerability. The withdrawn figure is set against a plain untouched canvas with only the outline of a couch. This is a stark comparison between the notoriously avant-garde set-up of his studio, otherwise known as ‘The Factory.’ Neel reveals a more wounded and humane depiction of the always controversial Pop artist.

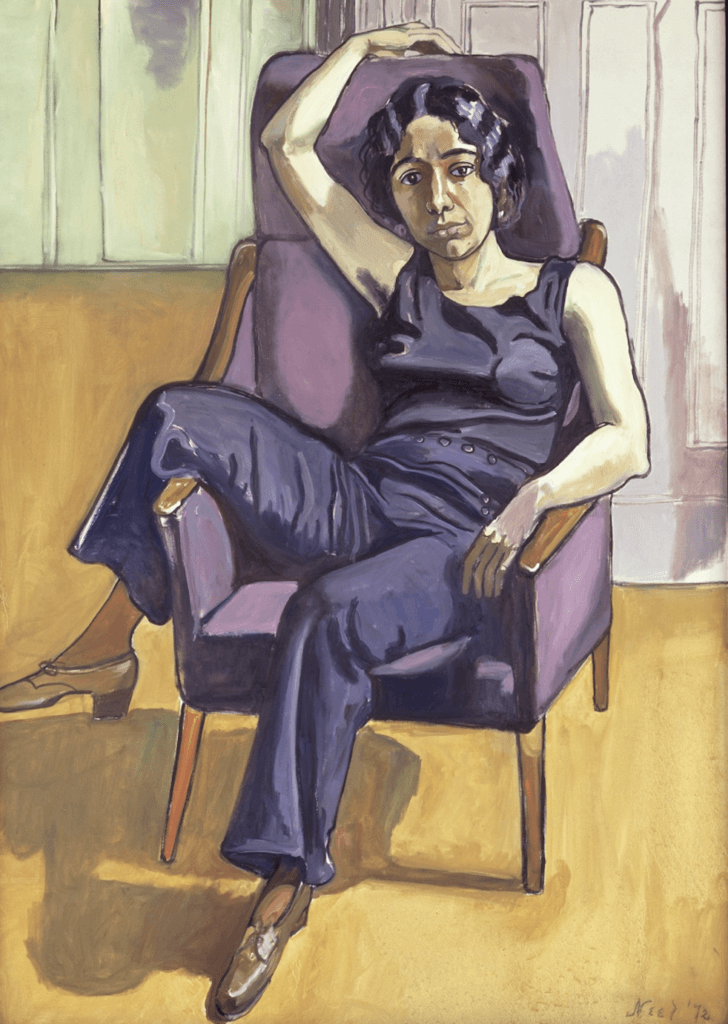

Another highlight was Neel’s Marxist Girl, Irene Peslikas (1972) – a portrait of another American artist who is one of the founders of Women and Art Quarterly and a member of the radical feminist group ‘Redstockings.’ Here, we see Peslikas dressed in purple, languidly reclining in an armchair (that is also purple) with one of her legs resting on the arm, quite suggestively but casually open in her body language. One of her arms is positioned overhead, revealing her armpit hair. With a confrontational but tender stance, Neel perfectly captures her radical spirit and I found myself immediately drawn to her nonchalance. Like Neel, she was a feminist and a communist who was famous for her socialist activism in feminism and the arts.

Marxist Girl was placed amongst portraits of other pioneering radical feminist thinkers, including Mary D. Garrard (1977), Linda Nochlin (1973) and Annie Sprinkle (1982). This was particularly interesting to see, for not only is Sprinkle a hero of mine but because Sprinkle rose to significant fame in the 1990s, showing Neel’s ability to discover an exciting talent for her subject matter. Such radical and progressive sitters confirm Neels’ status as an icon of feminist art – for her portraits at this time also included gay men and transgender artists, making her a precursor of intersectionalism in her art.

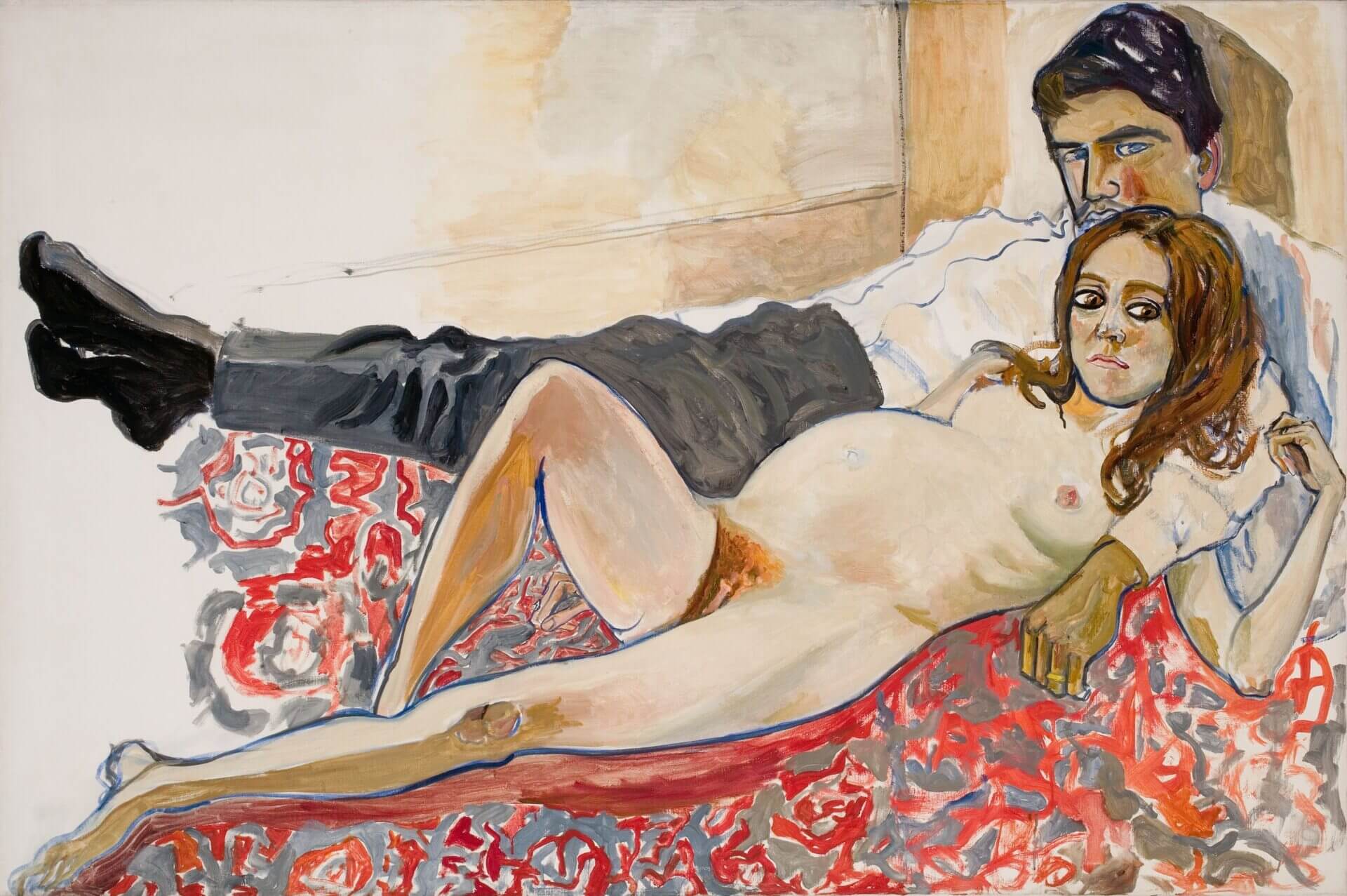

It is Neel’s female nudes which are always so captivating to me. Her stylistic approach rejects traditional models of portraiture shaped by male artists by freeing the conventional representation of the female nude from the objectifying male gaze. By embracing the curves and contours of the female form – whilst adopting an exaggerated fleshy colour palette – she remains committed to a more humanised representation of the female sitter that respects and celebrates her individuality. When female nudes have typically been passive, vulnerable, anonymous objects of the male gaze, this sets Neel apart from her male correlative for her bold and compelling portrayals of the feminine experience. In addition to the struggles Neel endured in her personal life, whilst exploring themes of gender, racial and class struggle in her art, this makes Neel’s oeuvre so impressive and why she is a pioneering figure in feminist art.