Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

In Near the Church of Santa Chiara. The killer’s game. (Palermo, 1982), a child stands behind a rough stone wall, a toy gun pointed outward with startling resolve. His small frame—clad in an oversized sweater—merges with the gritty textures of a Palermo street. The photograph is an unsettling juxtaposition of innocence and violence, play and reality. Letizia Battaglia captures more than a childhood game here; she reveals the way violence seeps into daily life, embedding itself in the gestures, spaces, and imaginations of the everyday.

This photograph is a microcosm of Life, Love, and Death in Sicily, an exhibition spanning Battaglia’s nearly fifty-year career, showing at the Photographer’s Gallery. While she is often defined by her documentation of Mafia violence—murders, judicial struggles, and funerals—Battaglia was equally attuned to quieter, deeply revealing moments: children at play in war-torn streets, women with silent resilience etched into their faces, and lovers entwined on sunlit beaches.

Curated without strict chronological or thematic chapters, the exhibition reflects the chaotic, deeply human nature of Battaglia’s work. In immersive sections like The Forest, where photographs hang suspended in a labyrinthine arrangement, viewers are invited to navigate Palermo’s stories on their own terms. The disordered layout mirrors Battaglia’s experience: raw, fragmented, and unflinchingly real.

This balance between brutality and beauty is central to Battaglia’s legacy. Her photographs are not merely documents of suffering but profound testaments to life’s persistence in the face of violence. By capturing both the mundane and the monstrous with equal sensitivity, Battaglia transforms photography into a tool of justice, witness, and empathy. It is this duality—despair and dignity—that cements her as one of Italy’s most significant social documentarians.

The Weaponized Frame

In On Photography (1977), Susan Sontag famously wrote that “photographs furnish evidence,” and nowhere is this truer than in Battaglia’s work. Her images do not merely record events—they indict. They challenge viewers to recognize the human cost of systemic corruption, situating her photographs as both historical document and urgent political calls to action.

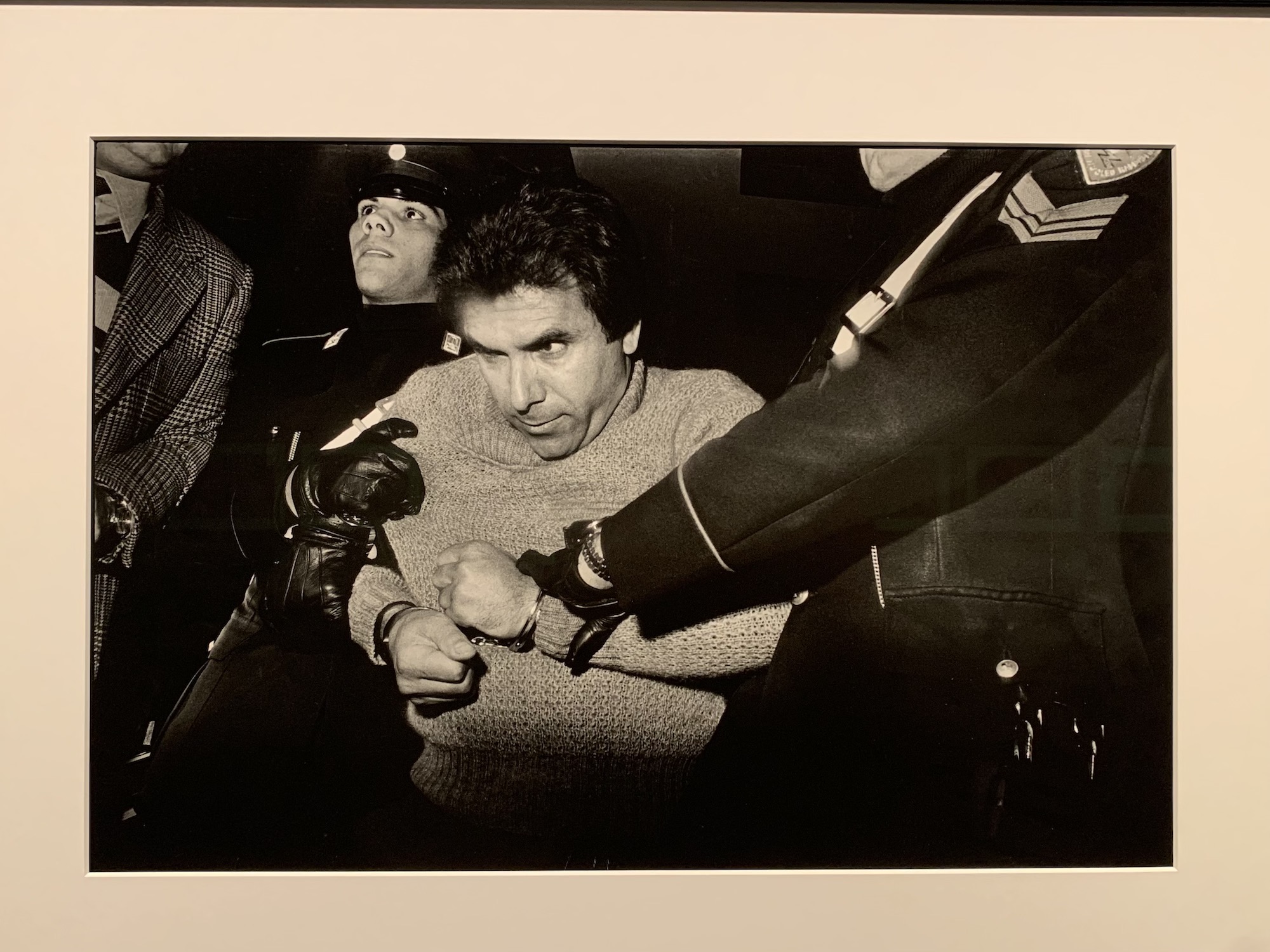

Battaglia’s work cannot be separated from her biography. Born in Palermo, she defied societal expectations to become one of the first female photojournalists in Italy in the crucible of Palermo’s violence during the 1970s and 80s. As Photo Editor at L’Ora, the city’s left-leaning newspaper, she documented Mafia murders, the aftermath of infighting between rival clans, and attacks on civil society. Her photographs served as vital evidence, disproving the myth that the Mafia’s violence was contained within its own ranks. Battaglia connected these crimes to corrupt politicians and exposed the broader impact of organized crime on everyday lives.

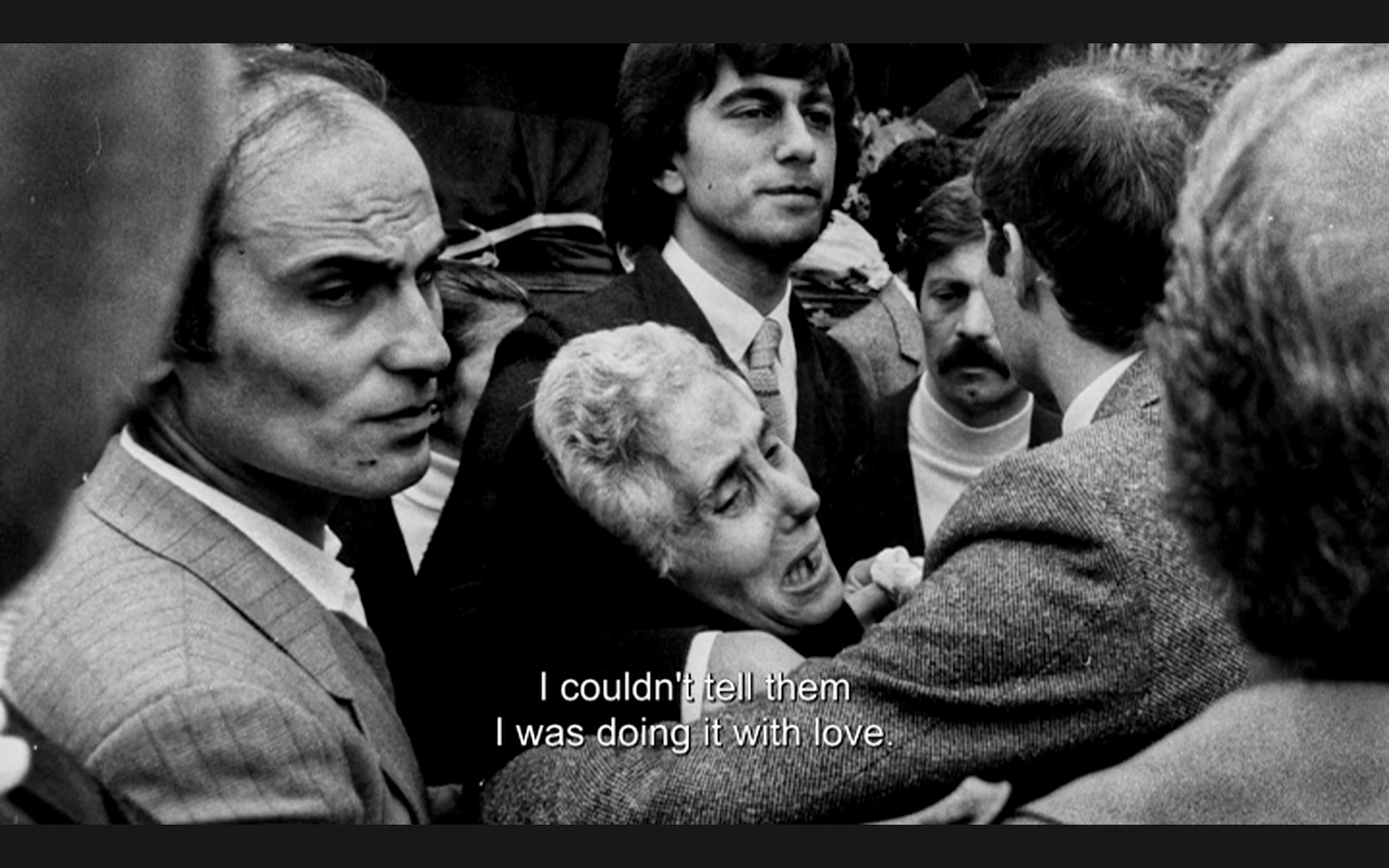

While Sontag’s concern that photography risks turning suffering into a spectacle is a valid critique, Battaglia’s work transcends a passive voyeurism. In Shooting the Mafia (2019), a documentary directed by Kim Longinotto, Battaglia addresses this complex nature of her work: “Photographing trauma is embarrassing. You love these people, but you have to take photos. I couldn’t tell them I was doing it with love.” There is a deep sense of empathy, care, and closeness in Battaglia’s work, as she fosters a deep empathy with her subjects.

Take, for example, the numerous portraits of widows and mothers mourning their dead. Rather than reducing grief to a tableau of despair, these photographs honor the dignity and strength of their subjects, framing them as central figures in the fight against injustice. For Battaglia, the photograph is not merely a record but an accusation, a direct confrontation with systems of power and silence.

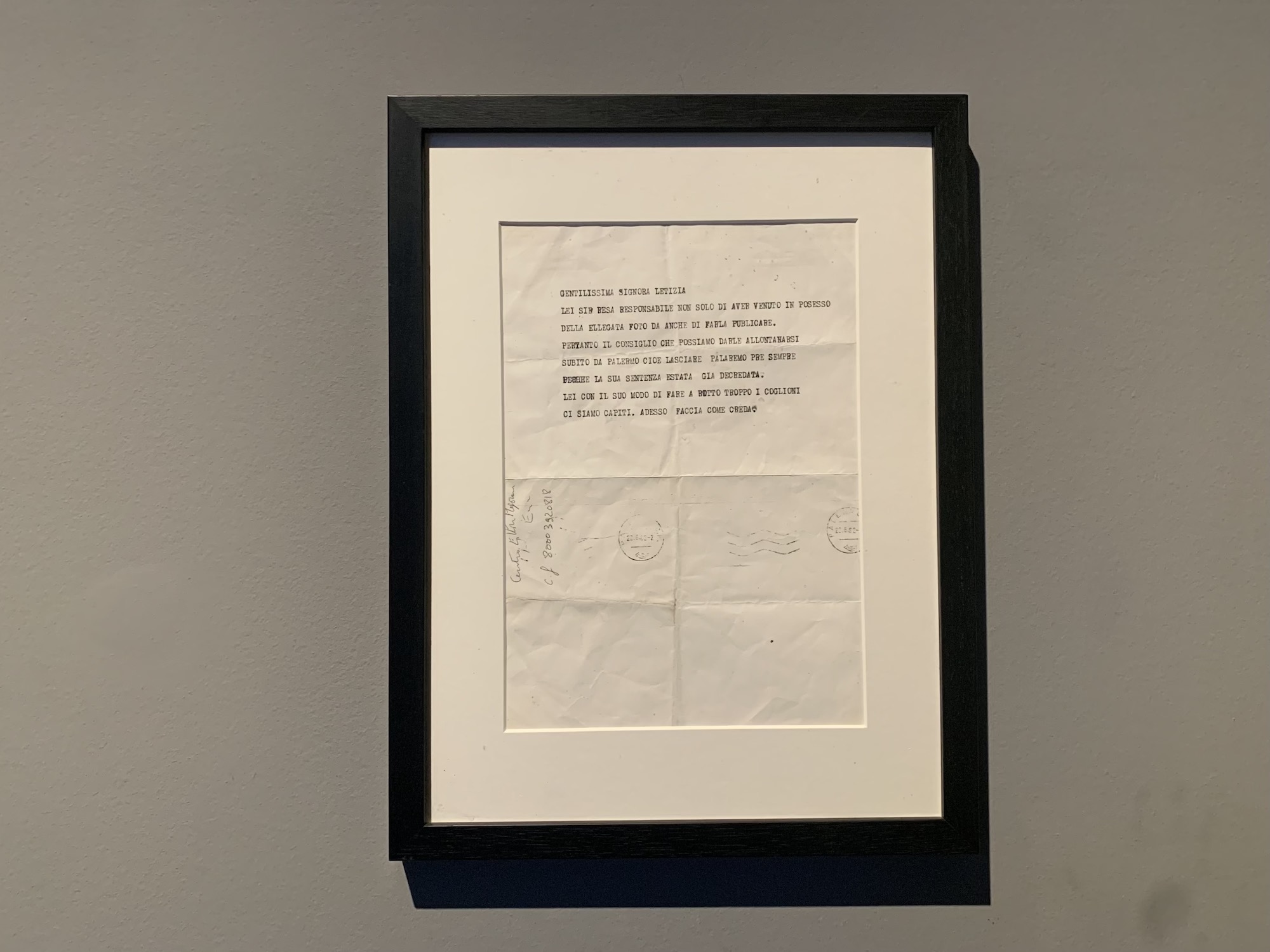

A Mafia threat letter received by Letizia Battaglia in Palermo (c. 1982-1983) is on display in the exhibition. The translated letter reads: Dear Mrs. Letizia, You are not responsible not only for having come into possession of the attached photo, but also for having it published. The advice we can give you is to leave Palermo immediately – your sentence has been decreed. With your way of doing things, you have broken our balls too much. Understood? Now do as you think best.

This chilling letter—both crude and chillingly casual—serves as evidence of the stakes she took on as a photographer: not merely recording events but actively disrupting a code of silence that had long enabled the Mafia to operate unchecked.

Life Amidst Violence: Battaglia’s Celebration of the Everyday

While Life, Love, and Death in Sicily undeniably confronts the pervasive themes of violence and death, it also revels in moments of tenderness, intimacy, and ordinary beauty. Battaglia’s photographs of two lovers on Mondello beach, and old lady walking with an ice cream cone in hand, Sabina and Pippo entwined in a gentle embrace offer viewers a reprieve from the starkness of her more confrontational images.

These scenes serve a dual purpose. On one level, they provide a counterpoint to the images of grief and brutality, reminding us that even in the darkest times, life continues to bloom in unexpected ways. On another, they underscore the stakes of Battaglia’s activism—what is ultimately being fought for is not just the absence of violence, but the presence of community, joy, and love.

On the Mondello beach. (Palermo, 1982), depicts two lovers at the forefront of the frame, in a kiss and embrace; in the background is the scene of an idyll beach day, with families and young people enjoying their sun-drenched day out.

In Sabina and Pippo in love. (Polizzi Generosa, 1983), the two lovers’ tender closeness feels universal, transcending their specific context while still being deeply rooted in the fabric of Sicilian life.

These moments provide essential tonal shifts, reminding viewers that Palermo’s story is not solely one of suffering but of love, resilience, and vibrancy. The exhibition text underscores this duality: “Although Battaglia is often remembered for her images of the Mafia, she devoted much of her own time to capturing everyday life in her hometown of Palermo.”

A Forest of Images

The exhibition’s curatorial approach mirrors Battaglia’s eclectic and dynamic process. In a section titled The Forest, photographs hang suspended from the ceiling, creating an immersive, maze-like experience. This innovative display recalls her 2015 exhibition Anthology in Palermo, where images were presented without thematic or chronological

constraints.

Walking through The Forest, viewers encounter unexpected juxtapositions: the aftermath of a Mafia murder placed near a candid moment of children playing soccer, or a tender embrace between lovers hung alongside a somber funeral procession. The absence of walls fosters a democratic relationship between image and viewer, allowing for a more personal and exploratory engagement with Battaglia’s work.

This curatorial choice reflects Battaglia’s belief that her photographs were not isolated projects but an interconnected lifetime project, a testament to the chaos and complexity of life in Palermo.

Life, Love, and Death in Sicily is a poignant reminder of photography’s power to confront, reveal, and celebrate. Letizia Battaglia’s images capture both the violence that plagued Palermo and the enduring humanity that thrived despite it. The exhibition’s immersive design invites viewers to engage with her work on a deeply personal level, walking through decades of Sicilian history and bearing witness to its complexities.

Battaglia’s photographs do more than tell stories—they demand action. They remind us of the stakes of justice and the beauty of resilience, urging us to see not just the scars but also the strength of a community that has endured.

Through her lens, Battaglia leaves us with an indelible testament to the enduring power of life, love, and the pursuit of truth.

Letizia Battaglia: Life, Love and Death in Sicily is currently on view at the Photographer’s Gallery until Feb 23, 2025.