Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

The divine feminine has long been central to artistic expression, embodying creation, wisdom, compassion, and destruction. From ancient fertility goddesses to warrior figures, representations of feminine divinity have evolved, reflecting shifts in cultural, spiritual, and societal values. The British Museum’s 2022 exhibition, Feminine Power: The Divine to the Demonic, explored these themes across civilisations, showcasing figures of goddesses, saints, and spiritual beings. Among them was an exquisite Figure of Guanyin with 18 Arms, dated back to the Qing dynasty, crafted from Blanc de Chine porcelain—an embodiment of how religious iconography adapts over time, particularly in relation to gender and the interplay of artistic craftsmanship with devotion.

Across cultures, divine feminine figures have played pivotal roles in mythology, religion, and artistic traditions. The Paleolithic Venus of Willendorf (c. 25,000 BCE) exemplifies early fertility symbolism, while the Minoan Snake Goddess (c. 1600 BCE) represents regeneration and female authority. In Hinduism, goddesses like Kali and Durga personify both nurturing and destructive forces, encapsulating a complex vision of feminine power.

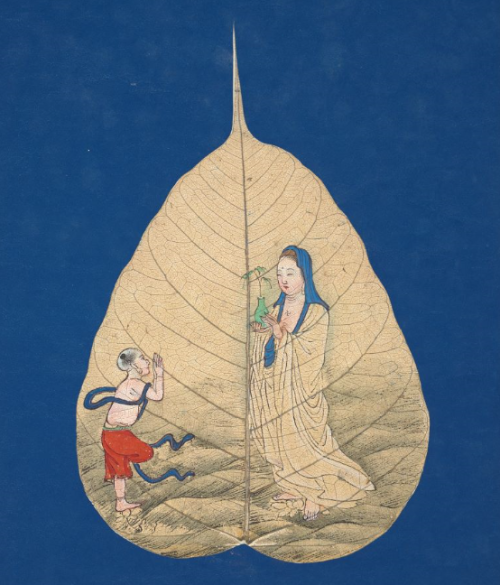

Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion in Chinese Buddhism, has undergone notable transformations. Originally Avalokiteshvara, a male bodhisattva in Indian Buddhism, Guanyin’s image gradually shifted in China, influenced by Daoist goddess traditions and evolving associations with maternal compassion. By the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), Guanyin was increasingly depicted in feminine form, a transition that became dominant by the Ming and Qing dynasties. However, some traditions, particularly in Tibet and early Japan, maintained an androgynous or male representation, highlighting the fluidity of Guanyin’s iconography.

The Figure of Guanyin with 18 Arms, exhibited in the 2022 British Museum show, exemplifies the refined craftsmanship of Blanc de Chine porcelain, a prized ceramic tradition from Dehua, Fujian province. Renowned for its unglazed, luminous white surface, this material allows for intricate detailing, enhancing the sculpture’s ethereal presence.

Seated in serene authority, Guanyin’s downcast eyes convey deep meditation. The multiple arms radiate outward, each meticulously sculpted to hold symbolic objects or form mudras (sacred hand gestures), signifying the bodhisattva’s boundless ability to aid devotees. Traditional attributes include the lotus (purity), the willow branch (healing), and the water vessel (compassion). The flowing drapery of the robes showcases the technical mastery of Dehua artisans, aligning with Ming and Qing representations of Guanyin as a figure of grace and divine serenity. The likely lotus-pedestal throne reinforces Buddhist iconography, symbolising enlightenment and transcendence.

Guanyin’s evolving iconography has also sparked discussions about gender fluidity in Buddhist traditions. The Lotus Sutra, a foundational Mahayana text, describes Avalokiteshvara’s ability to assume any form necessary to aid sentient beings, reinforcing a transcendence of fixed gender identities. Scholars such as Paul R. Katz argue that this fluidity aligns with modern discourses on gender and spirituality.

In contemporary practice, perceptions of Guanyin’s gender vary. Some Buddhist communities depict Guanyin as explicitly female, while others emphasize an androgynous or genderless form. In Taiwan, certain temples highlight this non-binary aspect, presenting Guanyin primarily as a bodhisattva beyond human distinctions. The 18-armed depiction further reflects adaptability—both in divine manifestation and in artistic expression.

While many worshippers focus on Guanyin’s compassion, current interpretations increasingly explore gender inclusivity. Within LGBTQ+ Buddhist discourse, Guanyin’s fluid representations serve as a symbol of transformation and acceptance. Beyond religious contexts, Guanyin appears in literature, film, and contemporary art. Taiwanese artist Li Chen, for example, creates abstract Guanyin sculptures that move beyond traditional iconography, emphasising a universal spiritual presence. In popular culture, Guanyin is often portrayed as a guiding force in narratives of redemption.

Ultimately, the Figure of Guanyin with 18 Arms represents the intersection of religious devotion, artistic tradition, and cultural adaptation. Its craftsmanship reflects the refinement of Dehua artisans, while its iconography embodies Buddhist principles of compassion and adaptability. Rather than offering a singular definition of gender or divinity, Guanyin’s representations shift across time and place, illuminating how divine figures are continuously reinterpreted.

Today, when discussions of gender identity, inclusivity, and representation are more prominent than ever, Guanyin’s fluidity offers a vital framework for understanding the intersection of spirituality and identity.