Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

‘SURRÉALISME AU FÉMININ?’ which opens at the Musée de Montmartre, Jardins Renoir, Paris, on 31st March explores women artists’ involvement in the surrealist movement from its inception in 1924 through to the 1990s and highlights the important role they played in shaping Surrealism globally. In an effort to shine the light on women surrealists, some recent survey exhibitions have been curated with a more equal balance in mind: ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today’ at the Design Museum, London, for example, showcased many works by female artists including Claude Cahun (1894-1954) Lee Miller (1907-1977) and Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) alongside their better known male counterparts Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), Max Ernst (1891-1976) and René Magritte (1898-1967). However, the exhibition also showed the lack of international recognition for non-western women surrealists who, aside from Remedios Varo and Frida Kahlo, rarely appear in international shows.

The Montmartre show’s ambition is to establish Surrealism as a global phenomenon. Presenting over 150 works by 50 women artists who formed part of the Belgian, British, American, Norwegian, Mexican and Czech Surrealist groups, the exhibition shows us how women participated in the surrealist movement through drawing, painting, photography, sculpture, poetry, writing and cinema. Both provocative and ambitious, these women artists invested in surrealism for its liberty of expression, translating their fantasies and developing their creativity in ways that often outshine their male counterparts. Long neglected by museums and undervalued by the art market, for artists such as Marion Adnams (1898-1995), Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988), Grace Pailthorpe (1883-1971) and Suzanne Van Damme (1901-1986), this show will be their first inclusion in a French, (and for some an international) survey exhibition. The timing of the exhibition is important, for as we come closer to Surrealism’s centenary celebrations, it provides us with a more truthful and meaningful account of one of the art world’s most celebrated movements.

For this blog, I will focus on four out of the ten + key surrealist works on loan to ‘SURRÉALISME AU FÉMININ?’ from the RAW collection:

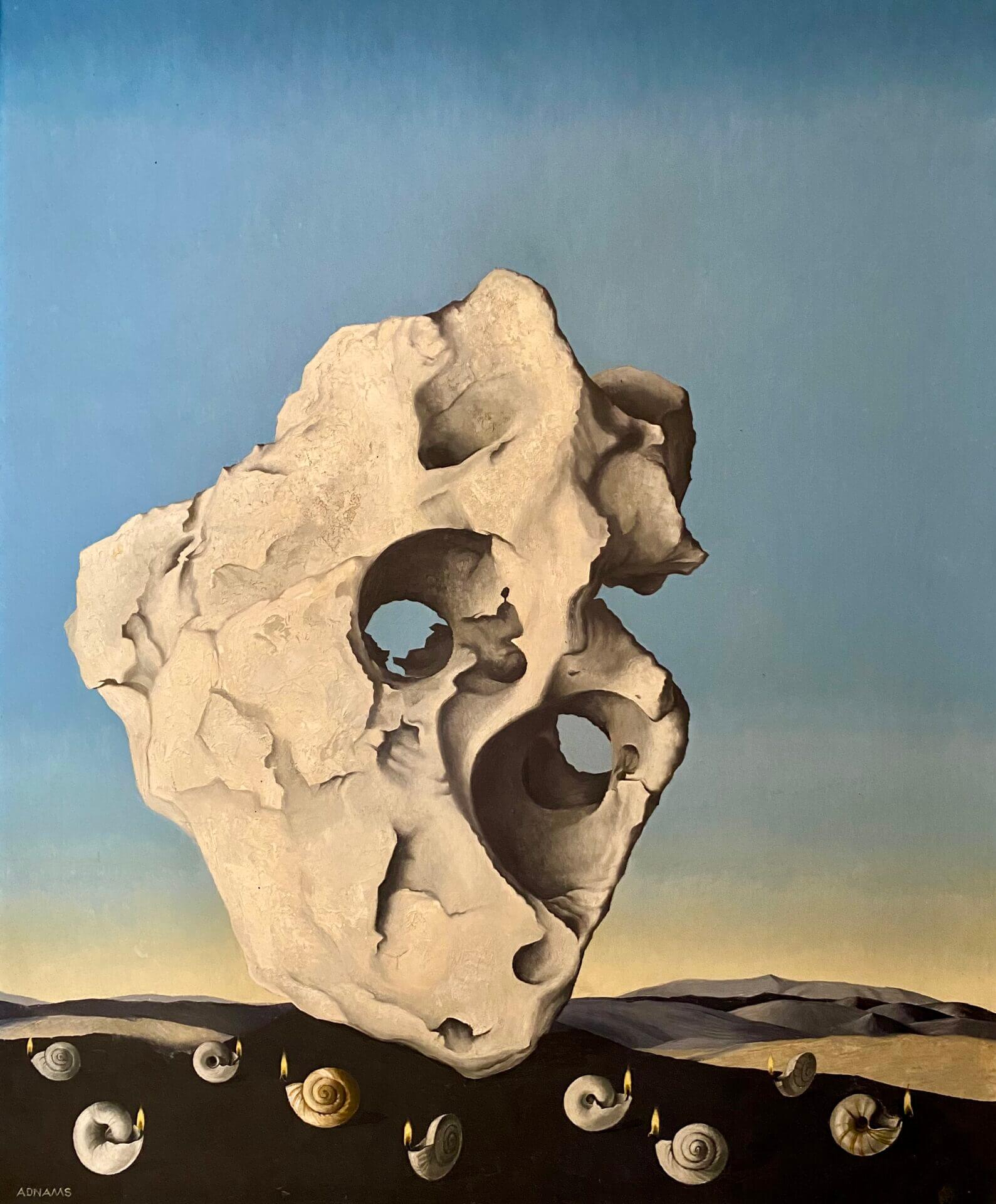

Despite having achieved recognition and commercial success during her own lifetime, Marion Adnams, who lived and worked in Derby, has since become something of a forgotten artist. Her inclusion with 3 paintings in the Montmartre exhibition finally gives us a chance to situate her work alongside international surrealist women artists and to introduce her remarkable vision to a new audience.

Adnams was fascinated by stones, shells and other objects found in the countryside, and she created disturbing juxtapositions to produce meditations on life and death. A Candle of Understanding in Thine Heart relates to a walk she made in 1964 in the Vaucluse, France, when she became captivated by a beautiful stone filled with holes: ‘The big stone had a personality. It stood silhouetted against the sky, silent and inscrutable, its many holes and cavities like un-seeing eyes. It was calm and dignified and yet at the same time there was something faintly disturbing about it’. Describing it as ‘a piece of modern sculpture’, Adnams posited, ‘Nature thought of the idea before Henry Moore!’. In her unpublished autobiography, The Enchanted Country, Adnams described how she set about creating this painting whose title is taken from the extra-canonical works of Estras. Setting the stone against a beautiful sky, ‘intense blue, changing to gold as it neared the horizon…a sunset calm’, she then juxtaposed it with nine snails – symbols of wisdom, persistence, and harmony – with a tiny flame burning in each so that they became little lamps. ‘I cannot explain why I saw the shells as lamps, but I was quite certain about it’, Adnams explained. However, three years later, when she returned to France and visited the little museum at Apt, the reason behind her use of snail-lamps became crystal clear to her: ‘I saw there, for the first time, a collection of Roman votive lamps, made of clay, and found frequently on the hills near here. In shape and size, they resembled exactly my snail-shell lamps’

Jane Graverol’s (1905-1984) surrealist works, which she created prolifically during the 1930s & 1940s alongside the up–and–coming Belgian surrealist group that formed around René Magritte, set her apart from her male counterparts: women, who in the male artists’ pictures are often portrayed as passive, fleeting and incidental, are in Graverol’s paintings given centre stage. Even when in the 1960s and 70s, Graverol moved towards a more figurative style, women remained central to her vision and, far from being seductive or titillating, her female figures can be read as powerful symbols of modernity and female autonomy. In this picture, which dates to 1960, a woman’s breast is unveiled by a dark red cape with a high buttoned collar, while a bird pecks at her nipple. This work was made in homage to ‘The Rite of Spring’ by Igor Stravinsky, a ballet whose theme is the return of spring and whose central narrative revolves around the sacrifice of a virgin obliged to dance herself to death – This ground-breaking work redefined the boundaries of music in the 20th century through its exploration of the unconscious. The parallels between Stravinsky and Graverol’s exploration of the unconscious resonate in this highly charged and deeply disturbing image which is poised so tantalisingly between reality and fantasy.

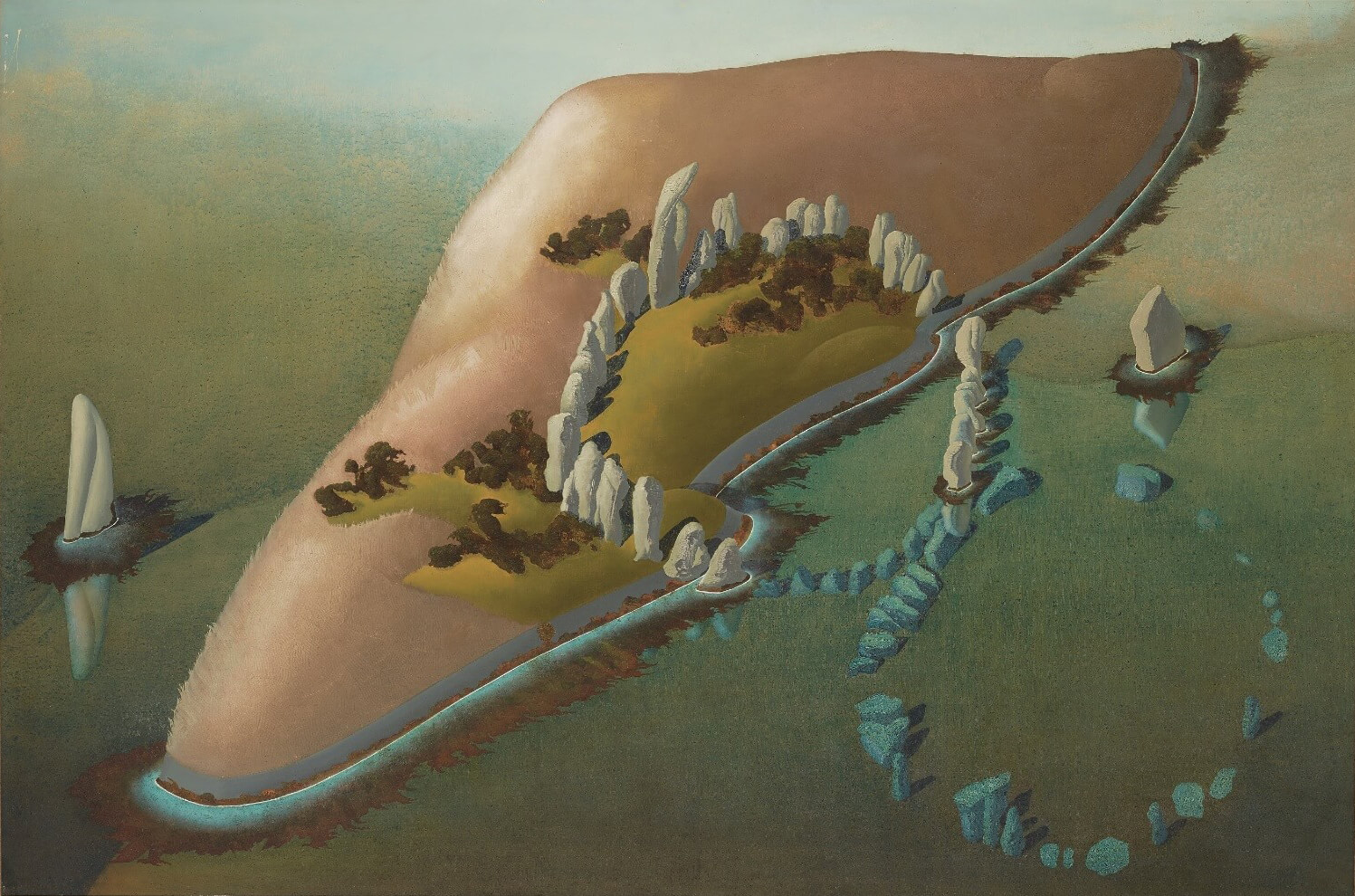

La Cathédrale Engloutie (trans: The Sunken Cathedral) is a 1950 aerial view of partially submerged stone monuments situated on the tiny island of Er Lannic off the south coast of Brittany. Initially, the monuments would have been both on land, but with time and rising sea levels one of the monuments has been partially submerged, only visible at low tide. While today the monuments are semi-circular, Colquhoun renders them in an idealized and pristine form as a cosmic lemniscate or infinity symbol, that which floats above the Magician in tarot decks but here flanked by two single megaliths emerging from the water. The title of the painting refers to the 1910 piano composition of the same name by Claude Debussy, who apparently shared Colquhoun’s animist sensibilities. Debussy was inspired by the Breton legend of the sunken city of Ys, where only the cathedral would still occasionally emerge on clear nights, filled with otherworldly music, only to recess back into the deep. This painting serves partially as a commentary on Colquhoun’s imaginings of ancient spiritual technologies where the true cathedral was forged from the living stones.

La Cathédrale Engloutie reflects several key themes in Colquhoun’s work: her interest in islands, stone monuments and the convergence points of land and water which Colquhoun held to be exceptionally powerful. Colquhoun painted other somewhat fanciful aerial views of antiquities, Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna) 1950 and Rocky Island (1969). Each of these paintings is arranged like a mythic ordinance survey map, reflecting deeper relationships with a fictional and idealized landscape of sacred sites. Colquhoun was also compelled by the mystery of sites which are submerged and re-emerge with tidal flows, a sacred rhythm of concealing and revealing, suggesting the Surrealist convulsive landscape and the breaking through of the subconscious mind to the conscious. Her Linked Islands I and II from 1947 also explore this theme through the story of the Old Man of Gugh standing stone and Santa Warna’s Well in the Isles of Scilly, two antiquities that Colquhoun visualizes as lovers, perpetually separated, and reunited by the motion of the tides. In La Cathédrale Engloutie the submerged nature of the stone cathedral is not to be mourned as a lost temple. Instead, Colquhoun recasts it as a mystery that speaks to elemental balance, a revelation of the convulsive landscape, the play of the seen and unseen, and an eternal meditation of time and tide.

This fantastical composition of mythological and imagined creatures silhouetted against a deep blue background is by a little-known Belgian surrealist called Suzanne Van Damme, who gained recognition after being invited by André Breton and Marcel Duchamp to exhibit in the 1947 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris. Les Lettres Françaises of 1947 drew comparisons between Van Damme’s work and that of Hieronymus Bosch in the way that she ‘casually put everything together without appearing to have a perfectly defined, deliberate aesthetic conception, although it seems on the contrary that everything is fortuitous and springing from it’.

With its strange, poetic vision, the work of Van Damme is also close to the magical imagery and techniques of the Belgian surrealist artists including Jane Graverol and René Magritte. The Belgian poet, Roger Bodart, characterised Van Damme’s art as a combination of reve eveillé (waking dream) and reve surveillé (controlled dream). This painting depicts morphing human forms merged with animal heads and body parts and is clearly inspired by celestial globes and maps, where similar constellation-like lines appear. On the maps, while these lines had a quasi-scientific purpose, for Van Damme they served as a creative device through which she could bind together the elements. “Imaginative is a mild adjective to apply to the extraordinary painting of Suzanne Van Damme!” the Studio Magazine wrote enthusiastically in 1948.