Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Lucas’ show at Tate Britain is a walk-through time itself. Her works – unlike the society she has dissected throughout her career- have evolved immensely.

Before you enter, you are met with Lucas’ overarching theme. FUCK DESTINY. Outside the gaping and somewhat intimidating doors, you find a sofa bed. Halfway through its process of being unfolded, it is punctured by a lightbulb. Colliding and changing the path of the sofa’s destination, the light de-rails it from its future, from its fate. Light – usually positive and prosperous – seems, at first, destructive here. But what if destroying a plan could be beautiful if derailment is better than staying the course? We are forced to rethink this sofa’s fate and with it our own.

The idea of destiny has heavily influenced Lucas. The underlying theme of the whole exhibition: disrupt the fate you were meant to fall into and push against what has been decided for you and one can see how she applies this to questions around gender, race, sexuality and class. The one thing all these categories have in common is their power to define your place in society; your role, and your future, which for many are predetermined. The works confront you, moving you to rethink how you move through the world: can we take control and veer off the road that is laid ahead? Can we regain power from those who hold it close?

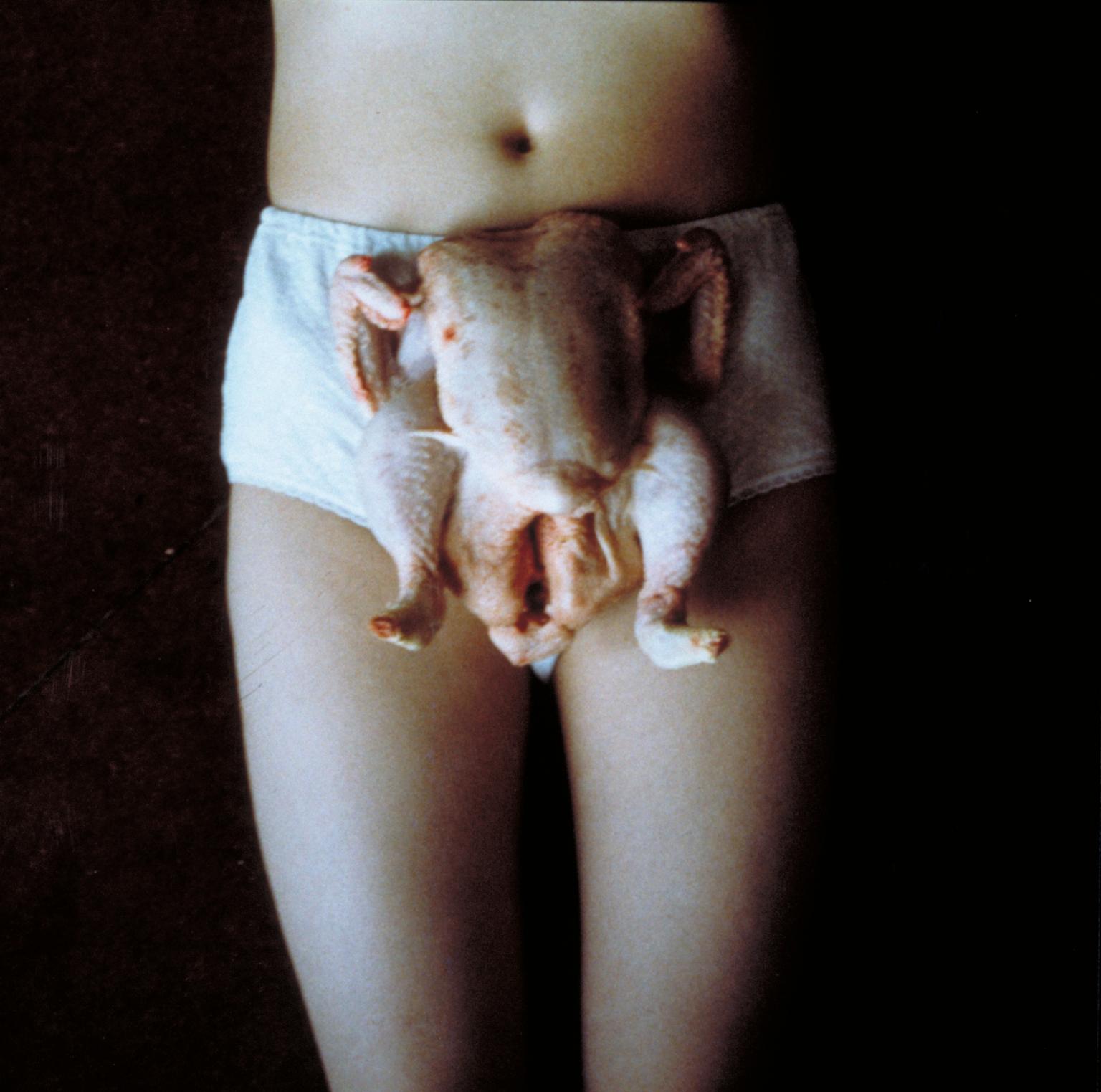

As you walk into the first room, you are faced with this question point blank. Blown up to scale the lofty heights of the somewhat oppressive walls, you are met with an image of Lucas donning a raw chicken, hung around her hips, pulled wide, its cavity emulating a vagina. A rugged reminder, often a vessel for the pleasure of the male gaze, the vagina is something that cannot be owned by the carrier. Something that can be abused nearly beyond the point of recognition, a space where violence can be played out; it is stripped of any autonomy. While certain bodies are put up for interrogation, for control, or dismissed, Lucas pushes back by owning her body throughout this exhibition, be it in the self-portraits covering the walls or the bodies sculpted that fill the space, she shows the ugly truths and beauty of existence. These threads, woven through a career which blossomed in the early 90s, alongside artists like Jenny Saville, take up relevance again today. Both Saville and Lucas found importance in portraying the hard and often heavy reality of what it meant to be policed, to have your body monitored, to have it controlled. This was a conversation that held a certain primacy among many artists of the 90s and finds an equally pressing need to be discussed today. Thirty years have gone by but very little has truly changed for many of us. If anything we are seeing arguably more repression, more censorship and sadly more lives being taken by the decisions of others.

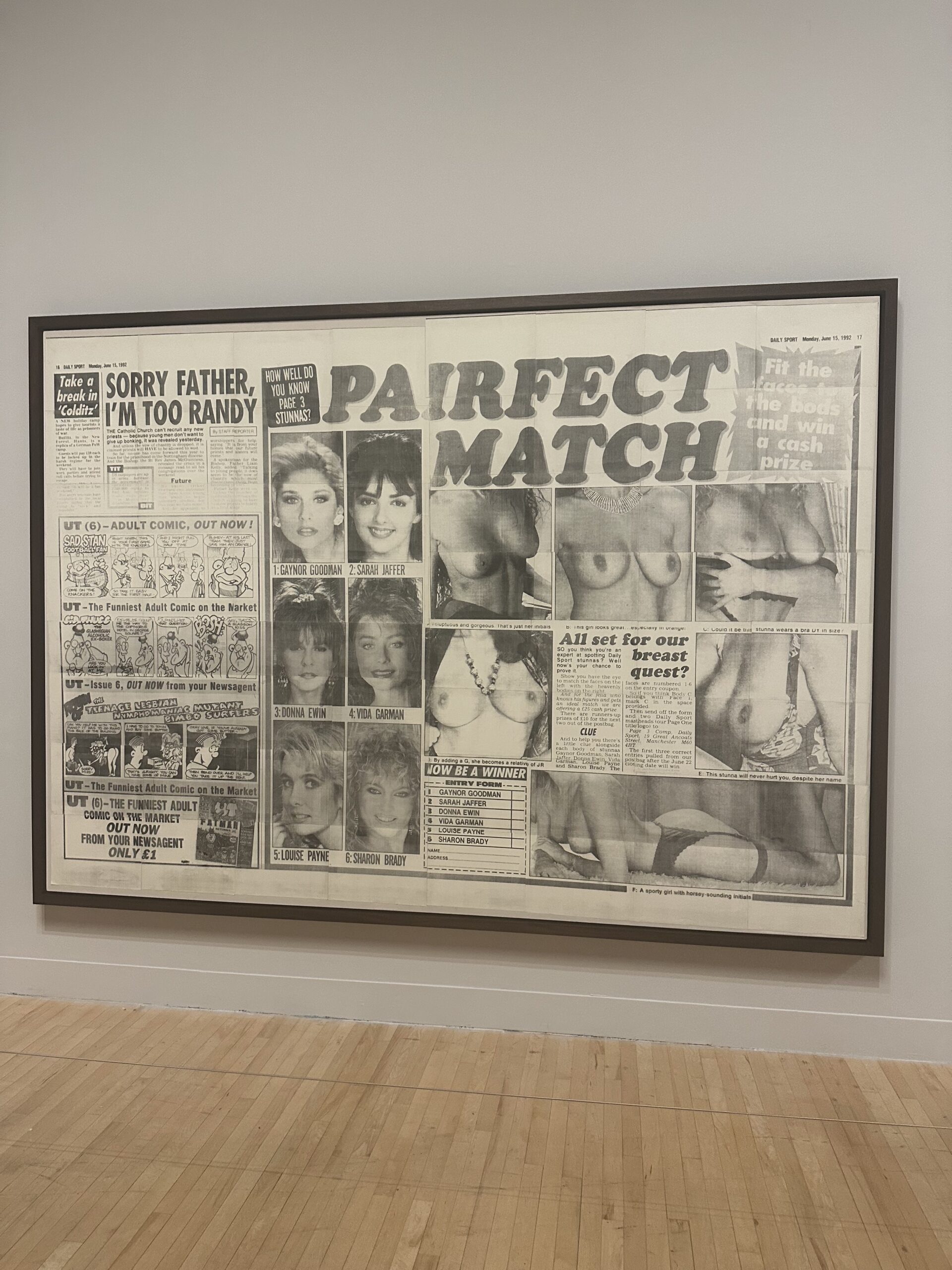

As you turn your head either way, patriarchy and misogyny take their seat once again. Wanker, an empty chair with an animatronic arm jerking off an invisible phallus is positioned to view Sarah’s chicken, as well as newspaper clippings from the early days of her career. Together with Wanker we truly can’t forget that nothing has really changed and why it’s still so important that we still discuss the topics Sarah has been engaging us in for years.

Sexism, misogyny, fat phobia not to mention fetishisation have remained unchanged for decades, enlarged articles from 1990-1992 surmise this all too well. Bunny (1997), a sculpture made of stuffed tights packed with wool, one of Lucas’ earliest and most renowned pieces, sits beneath these clippings, at once cementing the longevity of her work, but also highlighting the stagnation of society and the continued reticence to dismantle the oppressive structures of patriarchy and gendered violence.

Lucas’ sculptural work, at first glance repetitive, has adapted and advanced to fit into the climate it finds itself in. The cold and solid forms made in more recent years, moulded out of concrete and steel, reinvigorate Bunny, willing change yet simultaneously reminding the viewer of our own stagnation, we may all take on new forms, but history is nevertheless doomed to repeat itself. Cherry and Angel (2022) still softly sensual, whilst set in stone, displays the possibilities that everybody can be forged into, appearing hard and strong they maintain the ability to be fluid, to have curves and folds that spring out from the places you may not expect, to change and reshape, to reform even when there is control over them. Lucas’ choice to omit heads, eyes and hands, all features that are typically used to ascribe personal identity emulates the idea of perception perfectly. One doesn’t need an identity if others just see you as a body for their own pleasure – for their own plan. However, Lucas’ ownership of her body is of course a suggestion of ownership of all oppressed bodies. Potent in works such as Peeping Thomasina, a twisted and tangled pair of tights, wrapping around a metal chair, with nipples emulating eyes staring defiantly out at the viewer. To me, this body holds all the power, it heralds the notion that bodies which are often viewed as weaker and therefore lesser, still have autonomy, they have their own plan for life, they seek their own pleasures and they find their own joy.

Works such as Sadie, or even This Jaguar is Going to Heaven echo this idea of choice or freedom. A cigarette carefully inserted into a concrete anus, Sadie sets out the pleasure and the pain of self-determination. These are the vices we take pleasure in, but whether they be sex or smoking, anything can leave you swirling around the toilet bowl, so you might as well enjoy what you can when you can.

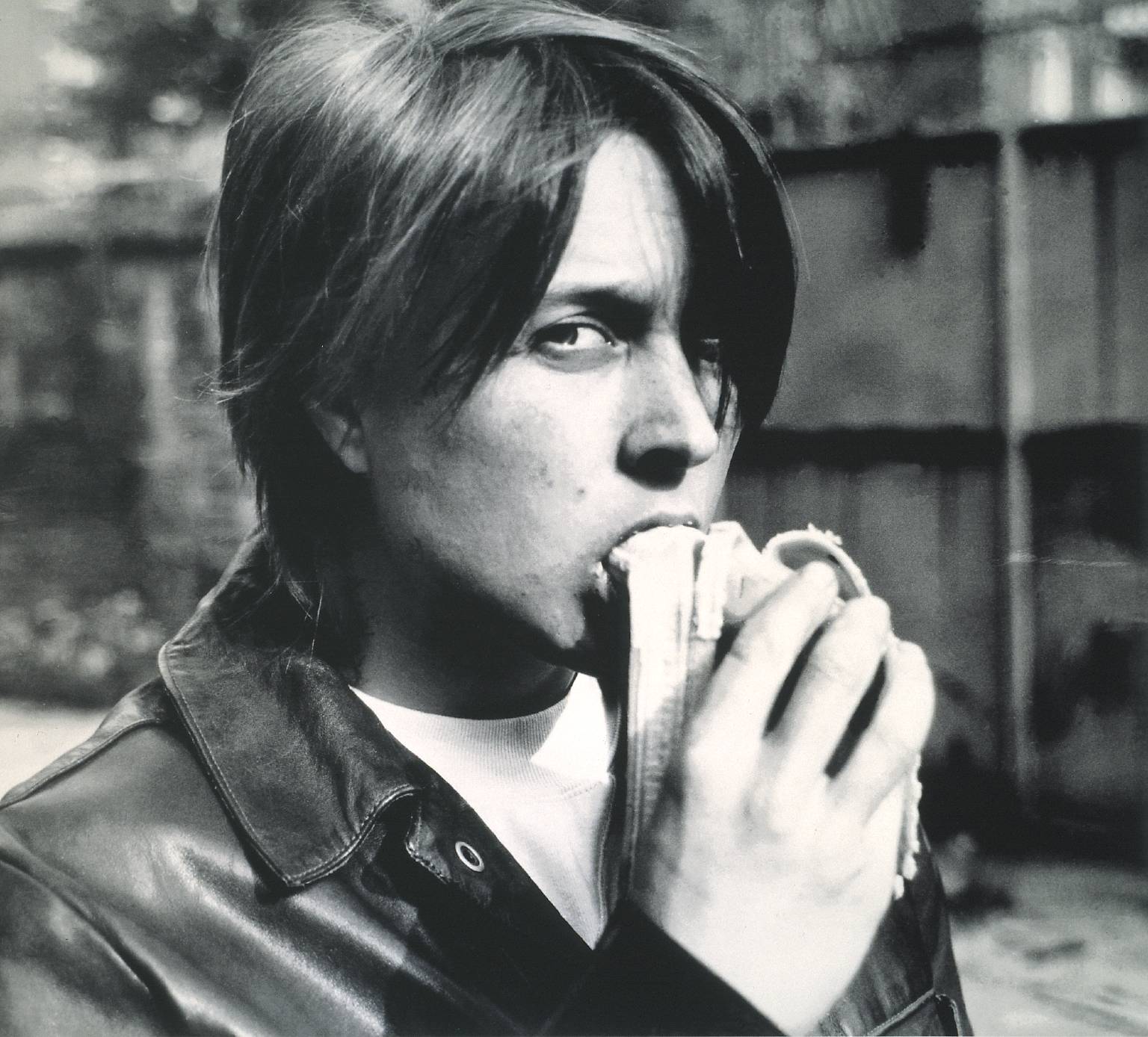

Is Suicide Genetic continues this narrative perfectly: a comfy chair burnt nearly to ashes, plinth to a motorcycle helmet covered in cigarettes. These objects that offer comfort or safety are tenuous at best and in some cases pointless, especially when living in a world that causes so much harm. In this world that seeks to suppress so many bodies and pleasures, is anything really safe? Is life worth living if we take no risks, if we conform, if we stop seeking out pleasures in the everyday? This Jaguars Going to Heaven displays the possible catastrophes we can experience in life. A car stands in for self and security – it is smashed to pieces, its chairs ripped out and strewn across the floor. The viewer is practically attacked by the fragility of life. If the journey is ideal, yet only to end with a crash, will the drive have been worth it? Banana continues this search for pleasure. A series of self-portraits of Sarah enjoying a banana, explicit yet joyful, she takes pleasure in this act, unabashed and unbothered by the observations of others. The omission of a face or even a body here is notable. Cis-gender male power is represented solely by a lone banana, chewed between teeth and the life sucked out of it. Here is the fragility of masculinity writ large (quite literally), and with it the fragility of patriarchy.

Many of the works sit atop cinder blocks. Appearing unbreakable, rigid and unwavering, these bricks seem firmly to hold up a status quo. However, upon closer inspection, their fragility unravels: light and filled with air they can be moved, they can be shifted, in fact, they can even be cracked. Their weakness is merely disguised in cold and abrasive sharp edges. The qualities of such a material are, of course, paramount. Inflexible, they smash, shattering when pressure is applied. The delicate positioning and care these sculptures hold is the only thing allowing these blocks to maintain themselves.

At one point I questioned for a moment if I found the show stagnant, I felt I’d seen it before. I considered whether we were really unpicking the violence of misogyny if artists were all using the same tools. So far unsuccessful in their goals, sexism is as rife now as it was then, I wished to see more of a move to her stone sculptural work or even that of her cigarettes, as this idea of retaking soft fabrics from the home ec classes of the 1900s I feel has been overdone. Then I remember Lucas’ tenure, like Tracy Emin and Jenny Saville, she committed herself and her works to reclaim the notion of femininity, to show the true power in owning oneself. Critical at a time when solo exhibitions by non-male artists were few and far between, her works still find relevance today. She and the other young British artists of her generation have heavily influenced those that followed and rightfully so, I see nods to her work in the paintings of Cristina Quarles or even the sculptures of Giulia Cenci. I recommend going to see this show to see where you sit within it. To see if you can find its references in today’s world. To see where it pushes you to. To see where you want to shift your body to next.