Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

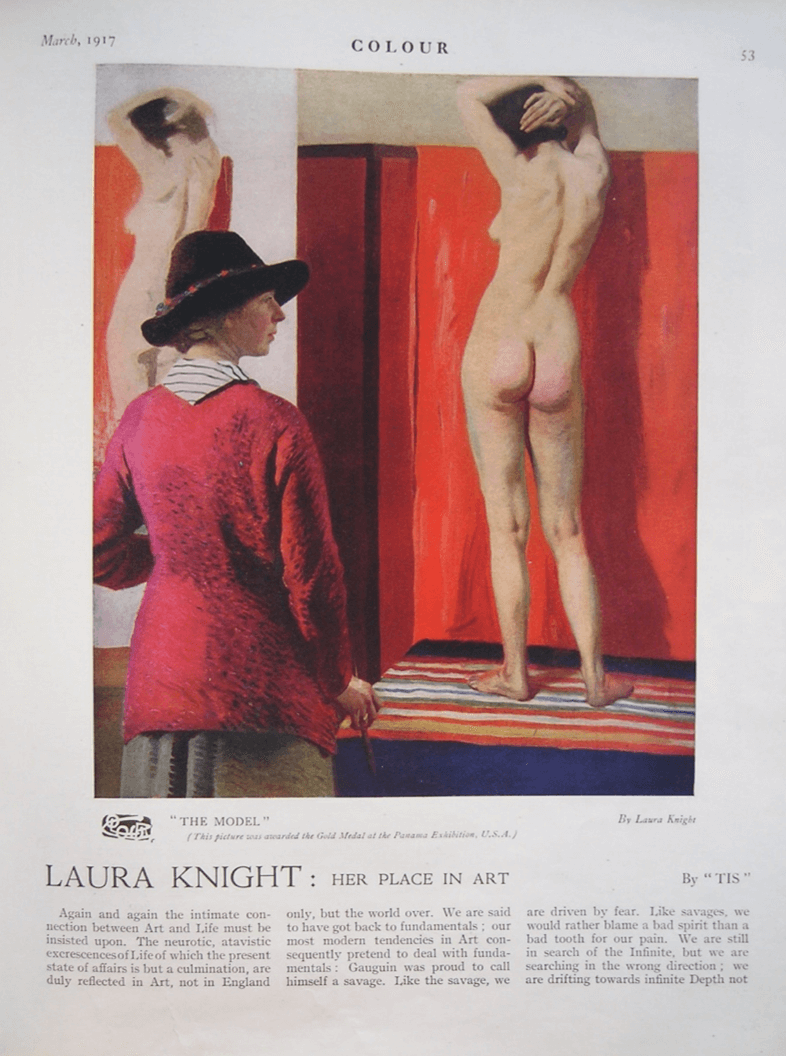

We have been seeing a lot of Laura Knight in recent months. Exhibitions in Penzance in 2021, in Nottingham in 2022, and, above all, the huge showing at the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, last winter, have brought her many new admirers. Despite being the artist of one of the best-known and most often discussed paintings in feminist art-history, Self-portrait with model (which she self-deprecatingly first exhibited in 1914 with the simple title of The model), Knight’s status as a true pioneer and standard bearer for women painters, in her own generation, and in ours, has been slow to gain universal approval. Her fame as the first woman to be elected to the rank of Royal Academician in the 200-year history of the institution (Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser, as founder members, were not elected), has been a two-edged sword: rather than ground-breaking, the position seemed to confirm her in the eyes of the progressives as middle-of-the road, tame and somehow compromised by association with a body struggling to reconcile itself to modernity.

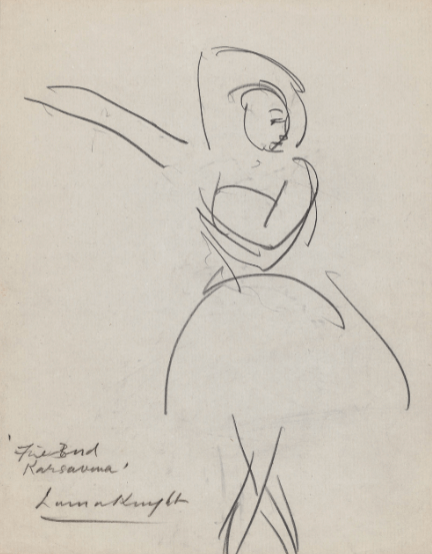

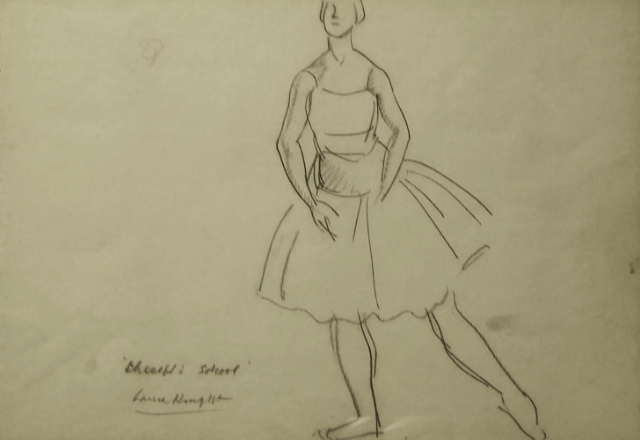

I first began looking seriously at Laura Knight fifteen years ago, while researching an exhibition of the ballet and theatre pictures. I was dazzled by Laura Knight’s colour, her ability to capture movement and her evocation of the sheer excitement which accompanied the London seasons of the Ballets

Russes before and after the First World War. But it was her pictures behind the scenes which were even more intriguing. In contrast to the work of Degas or Toulouse-Lautrec (to whom Knight did acknowledge her debt), where the presence of men in the wings can appear predatory, or voyeuristic, Knight was a woman among women, and an artist among artists. She exalted these female spaces with the pride that comes from the recognition of a shared love of craft. Drawing from a stage-side box, she set out to capture split- second poses with a few strokes of the pencil. In order to understand better what she was seeing, she also attended the morning classes, supervised by the aged ballet master Cecchetti. He was so impressed by Knight’s ability to capture the line of an arm or a leg, that he would tell the dancers to refer to her drawings to see where they deviated from his ideal. When she titled her second volume of autobiography The Magic of a Line, she was talking not only about her own medium, but the shapes drawn in space by a dancer, or for that matter, the somersault of the high-wire artist in the circus.

At the end of October, I shall be giving a three-week series of lectures at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, which will also be streamed on-line: Laura Knight: Woman and Artist. I shall be exploring aspects of her personal as well as her professional life, and showing a lot of contextual material from magazines and newspapers of the period. It is not widely recognised that Virginia Woolf read Knight’s 1936 autobiography, Oil Paint and Grease Paint, and wrote approvingly about her account of the prejudice met by a woman artist. In order to see Knight in the round, it is also important to gauge how she measured up to some of her prominent male contemporaries, such as William Orpen and Augustus John. Far from respecting the Victorian adage of ‘separate spheres’, Knight seems deliberately to have courted comparison with them, emboldened, perhaps, by the suffragists who were campaigning for equal rights during the very same years. But Knight’s approach was always collaborative, rather than confrontational.

We see this in the welcome she received in numerous marginalised communities throughout her career, from the fisherfolk of Northumberland to the circus and, finally, in the magnificent character studies of Romany gypsies she made in the late 1930s, undeterred by any escalating international tensions. Laura Knight died in 1970 at the age of 92, having been a professional artist for eight decades. After a long period of relative neglect, I think the time is right to rediscover more of the remarkable achievements of this determined and versatile painter.