Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Since the Renaissance – and before – Western art has been dominated by the male gaze. This has determined how women have been represented and seen – which means that more often than not, they are sexualised and beautified. Since the 19th century, with more and more women finding the opportunity to become artists, an alternative view to the male gaze has emerged. At times this has resulted in a reversal of roles – with the woman artist unapologetically sexualising their male subjects – but, more often, it has resulted in a much richer visual imagery in which multifaceted and different approaches to womanhood and sexuality have been explored. By depicting their own bodies, the bodies of other women and other sections of society that have been classified as outside norms, including non-binary and trans women, women artists have shown us what it truly means to be a woman. One artist who has explored all these trends is Amsterdam-based, South African artist Marlene Dumas, currently the subject of an extraordinarily beautiful monographic exhibition – titled “Open Ended” – at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice.

Spread over 2-floors, the exhibition is organised thematically, with the first floor – “Myths and Mortals”– taking its cue from the works inspired by Shakespeare’s poem Venus and Adonis, shown at David Zwirner in 2018, and the second floor – “Double Takes”, informed by Charles Baudelaire’s poem the Speen on Paris. Among the 100-plus pictures on show are many which explore one of Dumas’ favourite themes, the history of femininity. Calling into question the outmoded Western ideals of feminine beauty (bland, sentimental, saccharine and glossy), these pictures, overflowing, sometimes sordid, often joyous, but always realistically expressed, provide us with an alternative way of seeing. Based on her own first-hand experience, Dumas puts the focus on the physical and emotional reality of being a woman. Desperate for affection, consumed by sexual desire or violence, or marked by social and racial injustice, these intimate female subjects – based on media imagery, Dumas’ own photographs or her imagination – are emotionally charged, confrontational, unsettling and ambiguous and evoke all at once extraordinary strength and deep vulnerability.

Below, we shine the spotlight on a few of these pictures:

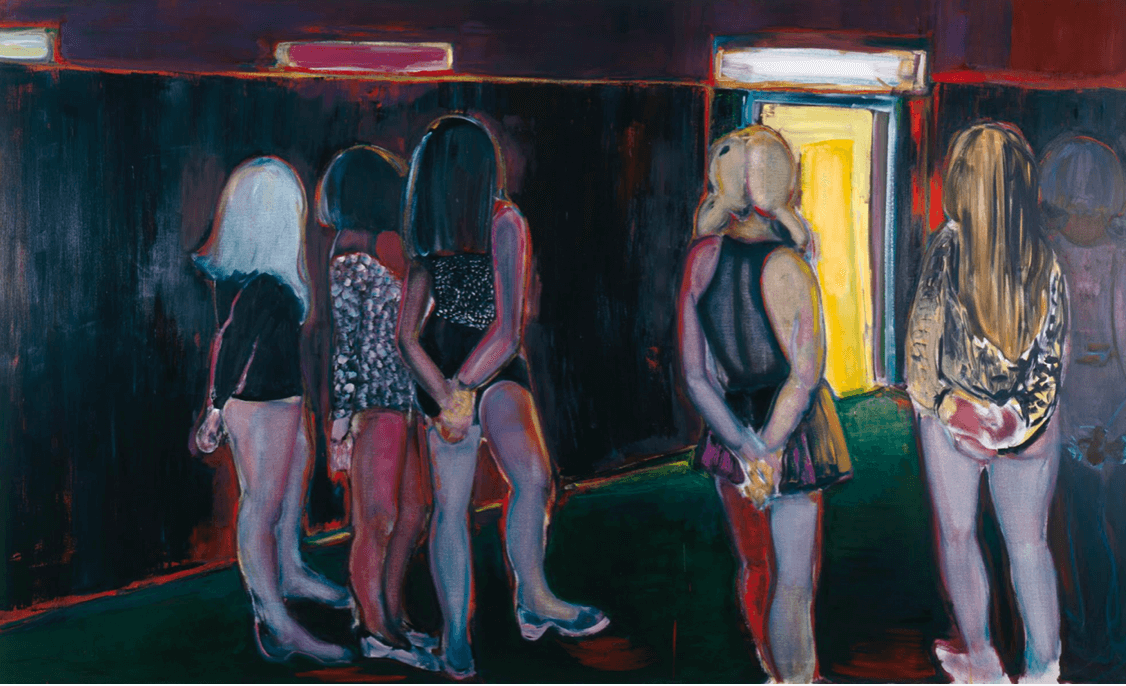

This composition offers a subtle reversal of the established tradition of paintings that situate the viewer (usually male) as voyeur, as exemplified, for example, by Manet’s Olympia (1863) or Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). In these paintings the women, presented frontal and naked, to be consumed by the male gaze. By contrast, in The Visitor, the women are presented from behind and we the spectator join them in expectation of their client who will arrive through the illuminated doorway.

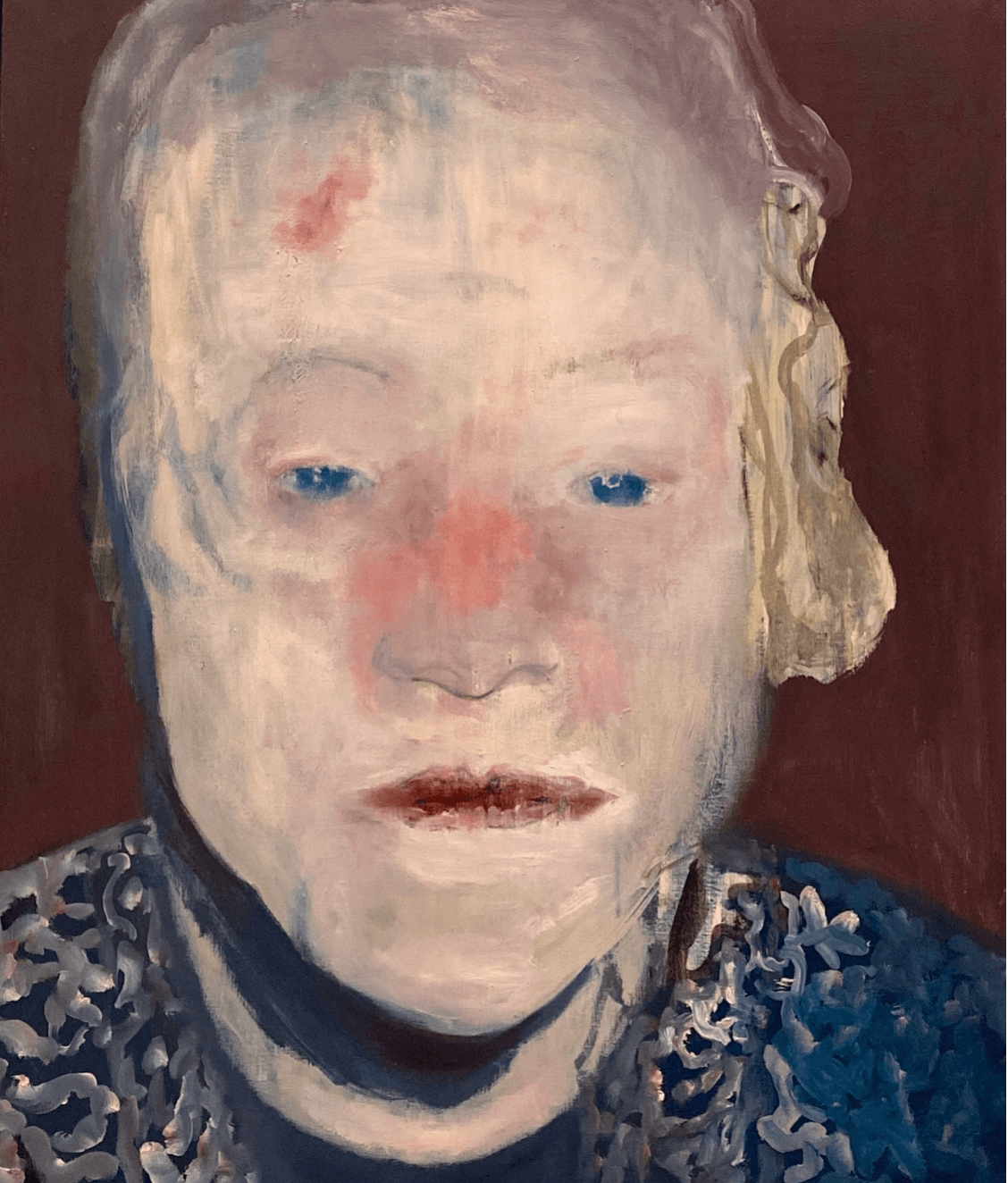

“Racism is still present-tense history worldwide. White people share a collective guilt that will not be forgiven in our lifetime”. (Marlene dumas, 1997).

This painting is based on a photograph taken by a friend of Dumas who worked at a dermatological clinic. The metaphorical title – The White Disease – likens the belief in white supremacy to a fatal disease of the spirit – racism – that has engendered centuries of violence.

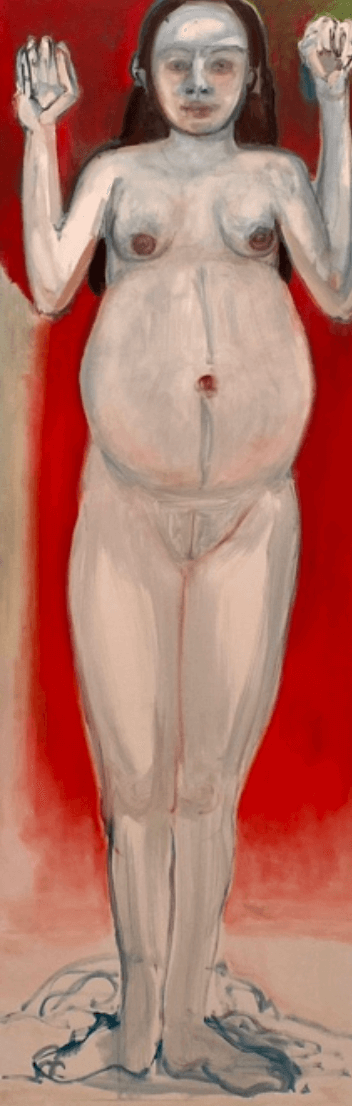

This larger-than-life image of a naked, pregnant woman was born out of Dumas’ endeavour to create a different and more honest type of Venus than those produced by male artists, such as the Birth of Venus by Botticelli. Dumas based this image on Inanna, also known as Ishtar, the Sumerian predecessor of Aphrodite and Venus, a powerful goddess of love, sex and fertility.

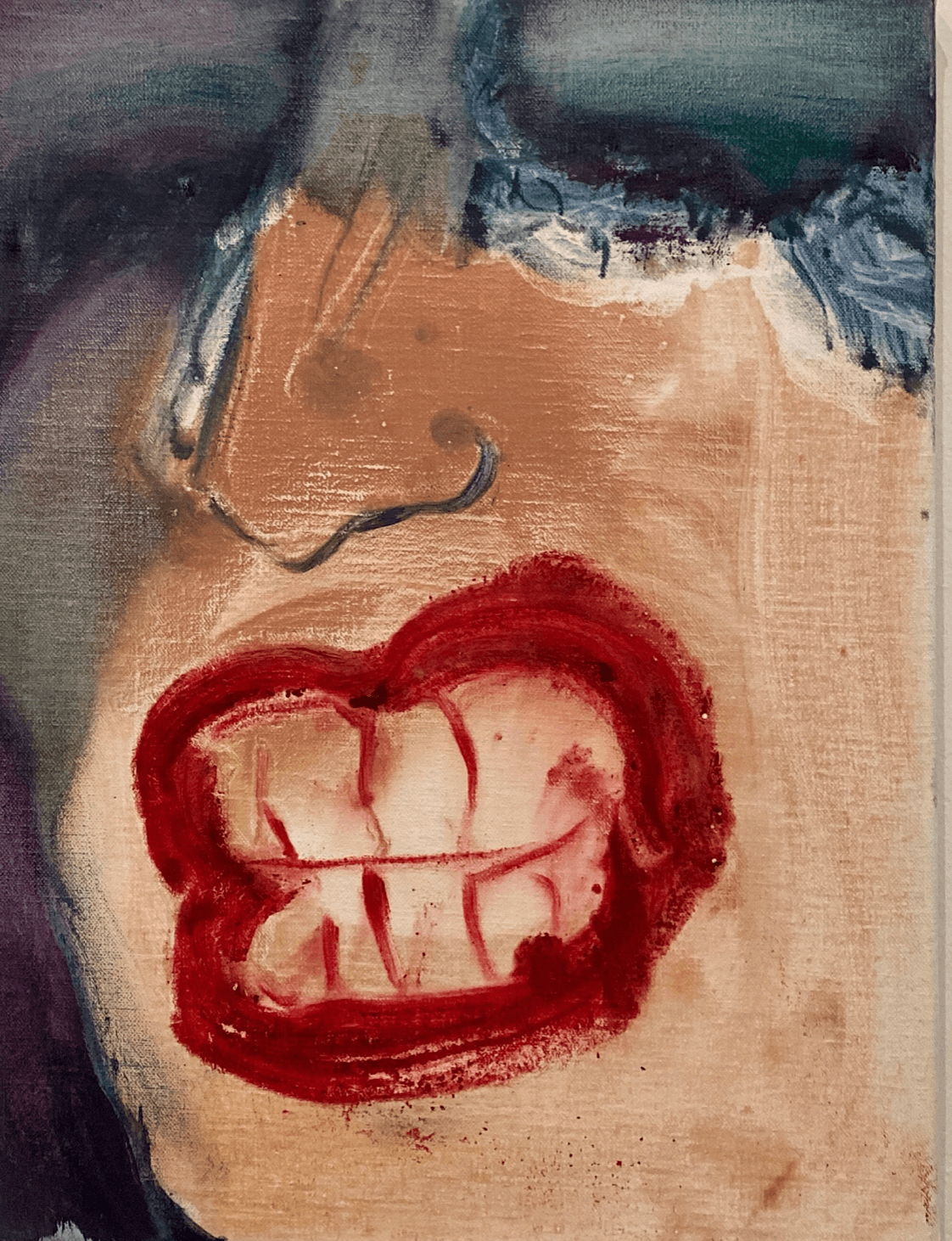

Dumas’ painting Teeth is a striking contrast to the soft, moist and inviting lips that we are accustomed to seeing in popular images and advertising. Far from pouting seductively, this mouth with clenched white teeth, is insulting and cursing – even threatening. Dumas has said that the image is based on a small black-and-white photograph of Maria Callas.

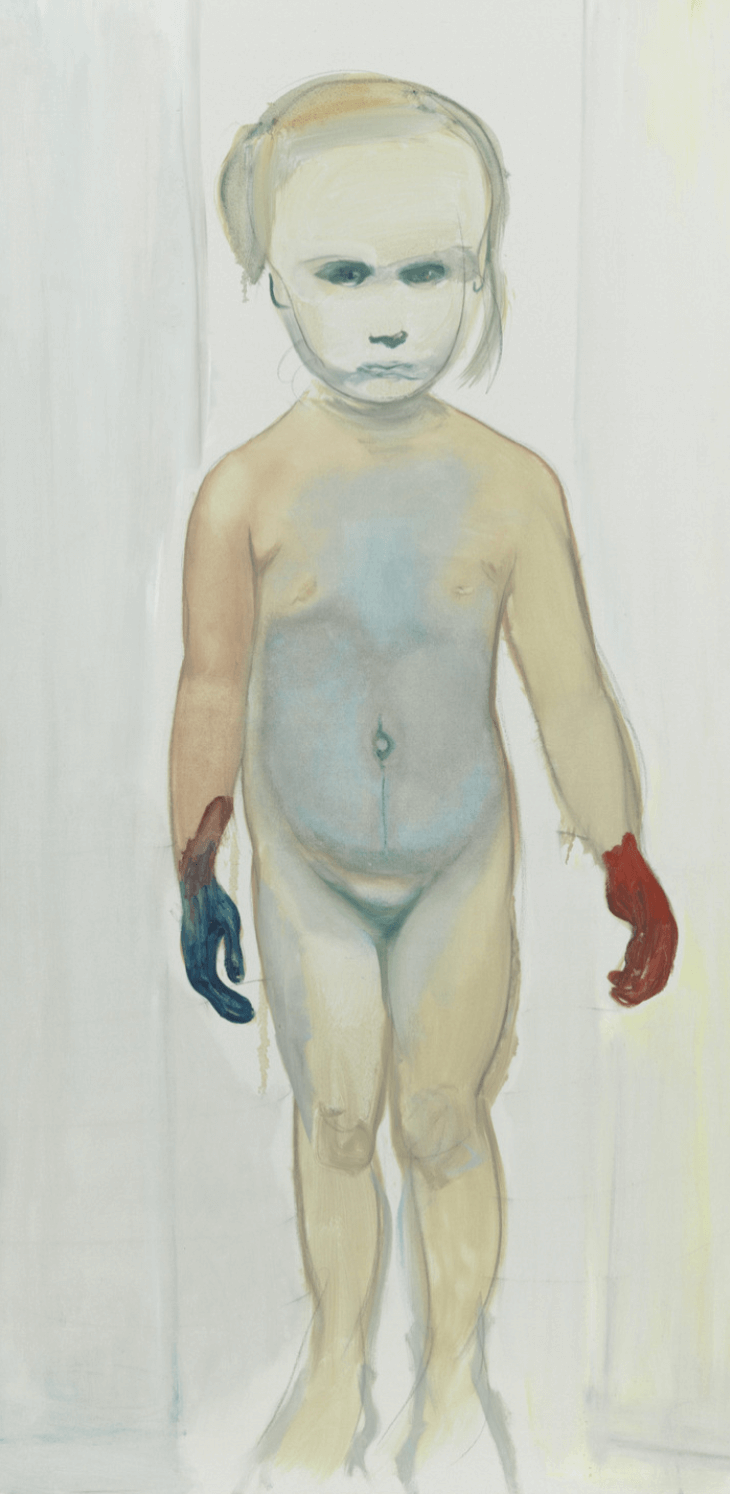

The intriguing title of this painting challenges conventional ideas about painters. In place of an adult male artist, the painter is a larger-than-life girl, who engages the viewer with a menacing stare, her hands covered in red and blue paint. Based on a photo of Dumas’ daughter as a child, the painting is deeply autobiographical.

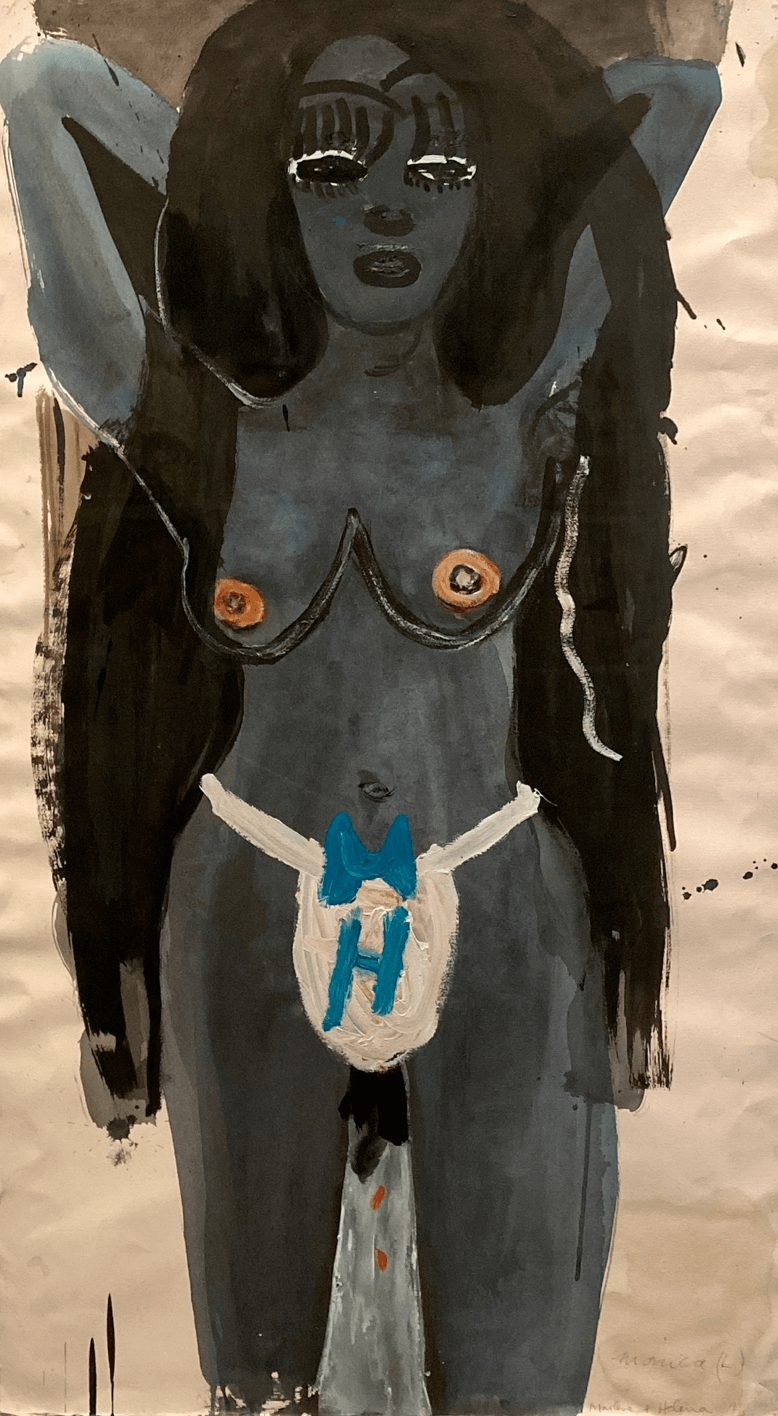

Monica( L), a collaboration between Helena, the artist’s daughter, and Dumas, shows a naked black woman with long black hair, confidently posed with her arms raised behind her head, staring directly out at the viewer. The composition is full of brooding symbolism and challenges the conventional gratification that paintings of naked women usually offer to a male audience: the breasts are accentuated as is the woman’s G-string, with its blue bow, but blood drips from between her legs.