Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

‘Even today, a female artist is considered more or less a freak, and may either be undervalued or overpraised’, wrote Laura Knight (1877-1970) in the 1960s. She had never had a choice of vocation. She went into painting as her trade, taking over her art teacher mother, Charlotte Johnson’s private pupils when she died, leaving Laura unprovided for at the age of 14.

When Laura’s famous near contemporaries, the Stephens girls, Vanessa and Virginia, spent three months every summer in a villa at St Ives, there was no money for holidays or new clothes in the Johnson household. Her scant training had taken place at the Nottingham School of Art where she enrolled as an ‘artisan student’ to save on fees. Here as a female student, she was denied access to the nude models in the life class, and asked, ‘why do you try to draw like a man?’

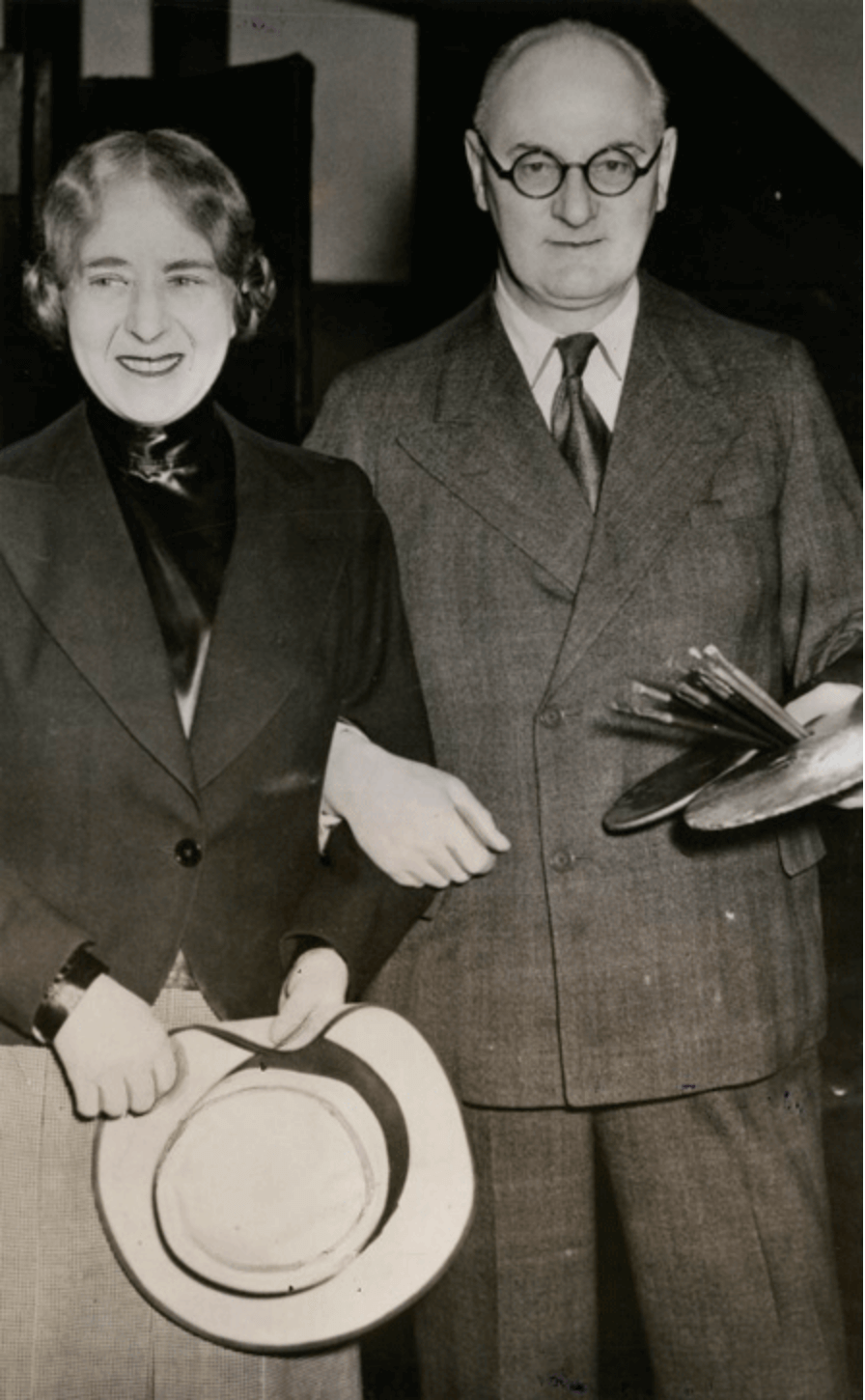

But having no male breadwinner to protect her at this stage may have been emboldening. Laura had apparently always wanted to be a boy. Her choice of a husband seems pragmatic: Harold Knight, a fellow artist whose rather withholding character was the inverse of her own, shared her commitment to painting. Laura was left relatively free from housekeeping, and without children they could live how and where they pleased. ‘Michelangelo had no baby’s bottle or teapot hanging round his neck,’ she later wrote. She also set down that it was she who had held her husband back in his career, without ever explaining how. Within the compass of her more conventional lifestyle, her marriage seems to have been as emancipated as those of the ‘Bloomsberrys.’

Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf had made comparable choices. Their parents’ death freed them from filial obligations and they had married men who sanctioned female emancipation and the creative life. But the Bloomsbury girls were raised in London’s intellectual aristocracy and then contrived for themselves the hot-house communities of Fitzroy Square and Charleston, feeding upon poetry, philosophy, literature and the imagination. By contrast, Laura Knight was self-avowedly literal-minded. Like those Victorian genre painters David Wilkie and William Mulready, she was also obliged to be single-mindedly commercial. She and her husband joined established artists communities and painted their established picturesque subjects. In Newlyn she painted huge Tuke-like pictures of bathing urchins in the harbour and appealing subjects such as Flying a Kite.

Roger Fry’s art history and the impact of the Post Impressionist exhibition of 1910 had confirmed Laura Knight as a traditionalist, just as she was becoming famous and successful. Friends wondered why she did not capitalise on her successes, but her move in 1913 to the more self-contained artist’s community in Lamorna when she was in her 30s represented a kind of epiphany of creativity and discovery for her, when (she said) she finally ‘found something all my own.’ The paintings of female friends and models naked or part-clad, out of doors or contemplative, in intimate settings, that she made now were more exploratory, while maintaining a marketable allure. Meeting the already established painter Alfred Munnings in this febrile state of mind she took him as a guru, embodying bohemian freedom, and her decisions to make paintings of tramps and gypsies and circus and theatre performers can be traced back to her admiration for his take on life.

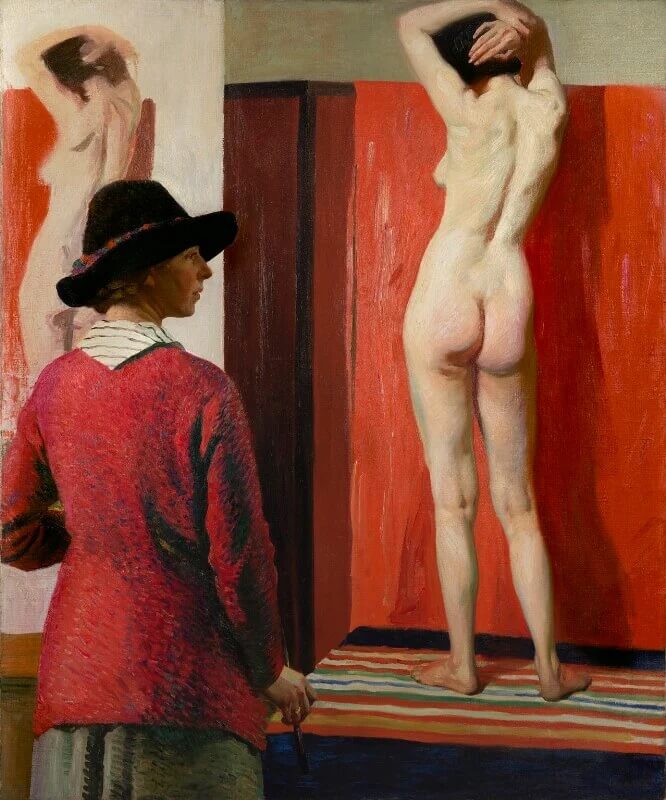

Her Self Portrait with a Model of 1913 was a determined assertion of equality, aimed at the Royal Academy and the wider art establishment. The scepticism with which it was received may have taught her not to step so far beyond bounds again, for her portrait was labelled as ‘vulgar’ in the Daily Telegraph when it was shown in London (the identical term resorted to by the Daily Mail’s critic Quentin Letts to sum up Tracey Emin’s White Cube show almost exactly a century later, in 2014). Tellingly, Knight’s Self Portrait would remain in her studio and was only acquired by the NPG after her death.

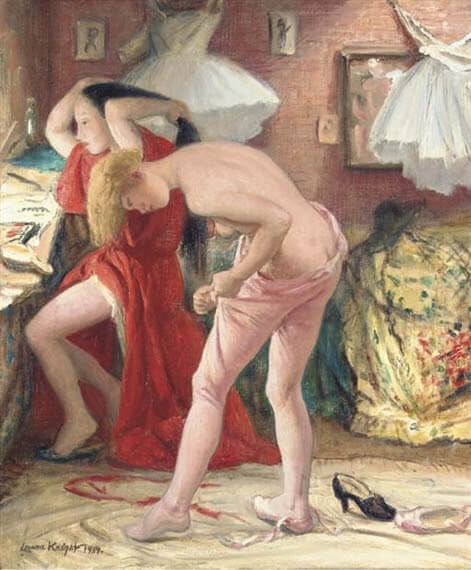

When the war and Harold’s miserable experience labouring on local farms as a conscientious objector sent them back to London, she hit upon the Russian ballet that was all the rage, creating a furore there. She described the girls in whose dressing rooms she painted as fellow ‘workers,’ herself as another working artist rather than a woman artist. Her depictions of women brought her to contemporary notice, as being at the forefront of women’s advancement. But by the time she was elected ARA in 1927 and then RA in 1936, more progressive artists had rejected the institution. Knight had elected to adopt a vision that was journalistic, but with privileged female access, capturing ‘types,’ physical movement and historical events; her backstage pictures showed a knowledge of Degas and Lautrec but had nothing outré or louche about them. Later there were propaganda images of Britons at war on the Home Front and outstanding British war workers that led to her being sent to document the Nuremburg trials. But summing up her own experience in old age, she reckoned it the female lot to be cut off from the ‘thunderbolts of the imagination’ that were available to men.

Laura Knight wrote two volumes of autobiography ensuring that she was the recording angel of her own life, emphasising early struggle and difficulties vanquished, her ‘self-made’ virtues and lack of privilege. In her time the freedoms and recognition that she achieved were large ones, and her subjects – ballet dancers, circus performers, tramps, factory girls and gypsies – were enacting a ritual of ‘freedom,’ too. But since then, posterity has been less kind. Decades after the President of the Royal Academy included Knight as ‘one of us,’ women are still often defined by their flaws. The assertiveness and prodigious output summed up by Kenneth Clark as having ‘the courage of its own commonplaceness,’ have not served to make Laura Knight an obviously appealing woman (the terms ‘commonplace’ and ‘vulgar’ are synonymous, both can also imply the meaning ‘plebeian’). Perhaps Knight seems both too competent and too invulnerable for contemporary tastes, a poster girl for feminist art history with none of the outsider-pathos of that most timely new arrival for female canonisation, Marlow Moss.

‘Now that womankind is no longer born to hold a needle in one hand and a scrubbing brush in the other, what great things may not happen?’ she wrote in 1965. Dozens more women artists were earning their competence as teachers or commercial artists during the same century – compare the careers of Barbara Jones and Peggy Angus with that of their contemporary Eric Ravilious – but none were as famous. With them comes Gwen John, followed by Barbara Hepworth and then, at long last, Tracey Emin. But for women artists, the list of household names remains much too short.