Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Of the 19 poets and artists who appeared in André Breton’s first Surrealist manifesto of 1924, not one was female. In the second manifesto, published a few years later, Breton declared: ‘the problem of women is the most marvellous and disturbing problem in all the world’. Against this backdrop, it is remarkable how many women artists played a major role in Surrealism, and yet they are only now beginning to receive the recognition they deserve. By focusing the RAW collection on women surrealists, we hope to highlight and promote their remarkable and unique contributions to the movement.

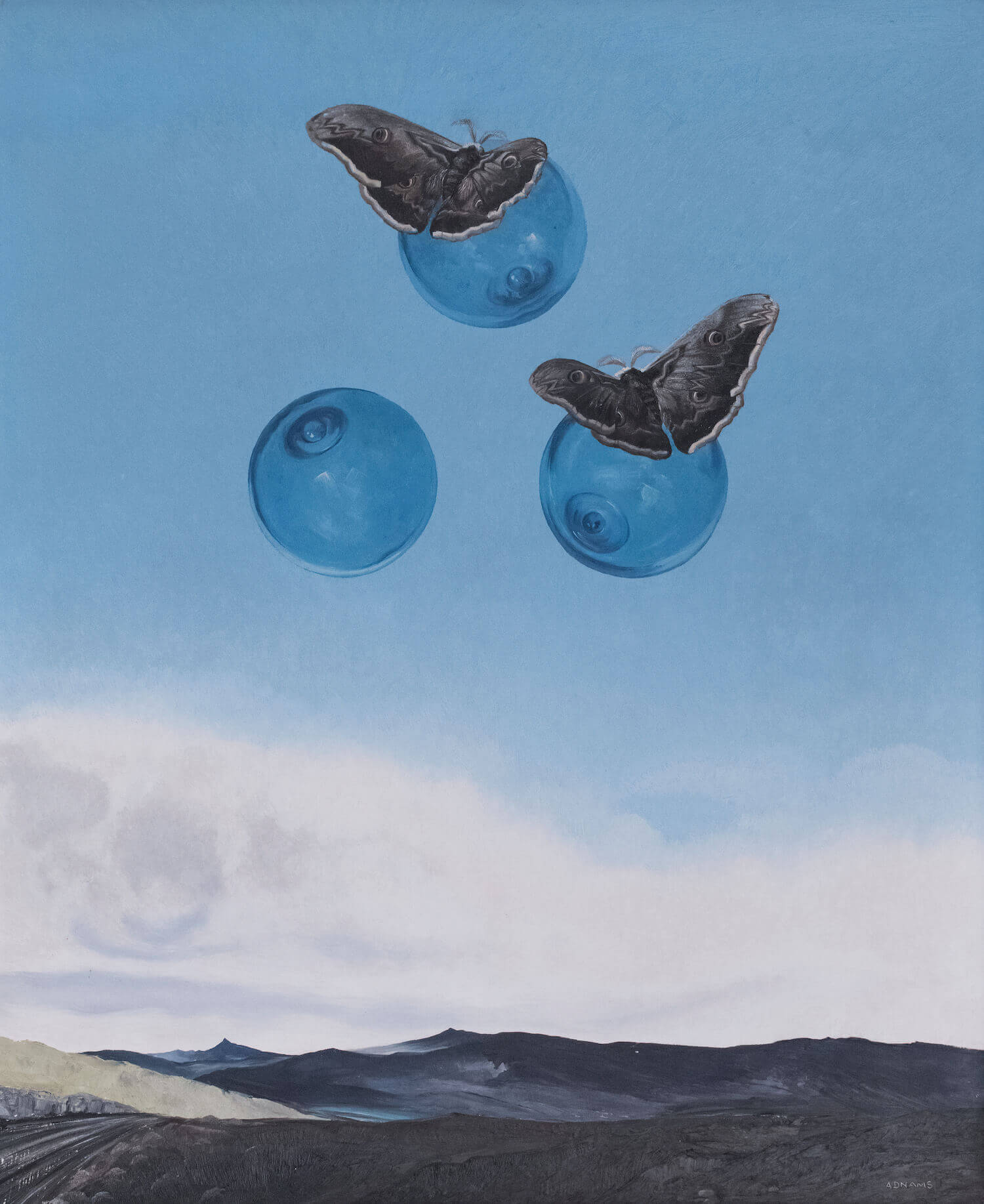

We recently added 2 works by the Belgian surrealist Susanne Van Damme to the collection. She hasn’t appeared in any major surveys of surrealism, including ‘Fantastic Female Surrealists’ at the Schirn Kunsthalle and yet she was a major player in the Surrealist movement, exhibiting at the 1947 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris at André Breton’s invitation. Unfortunately, many of the reproductions of her early surrealist works seem to be only available in monotone and only one public collection – the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique – owns her work.

Yes, things are beginning to move in the right direction. Scholars like Witney Chadwick have been waving the flag for years, and her scholarship has been invaluable to our understanding of women’s contribution to Surrealism. There is an ever-increasing number of monographic and group shows about women surrealists (for example ‘In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States’ (LACMA 2012) and ‘Fantastic Female Surrealists’ at the Schirn Kunsthalle 2020). Women surrealists are also finally fetching important sums at auction, which is an indicator of their ascending stars.

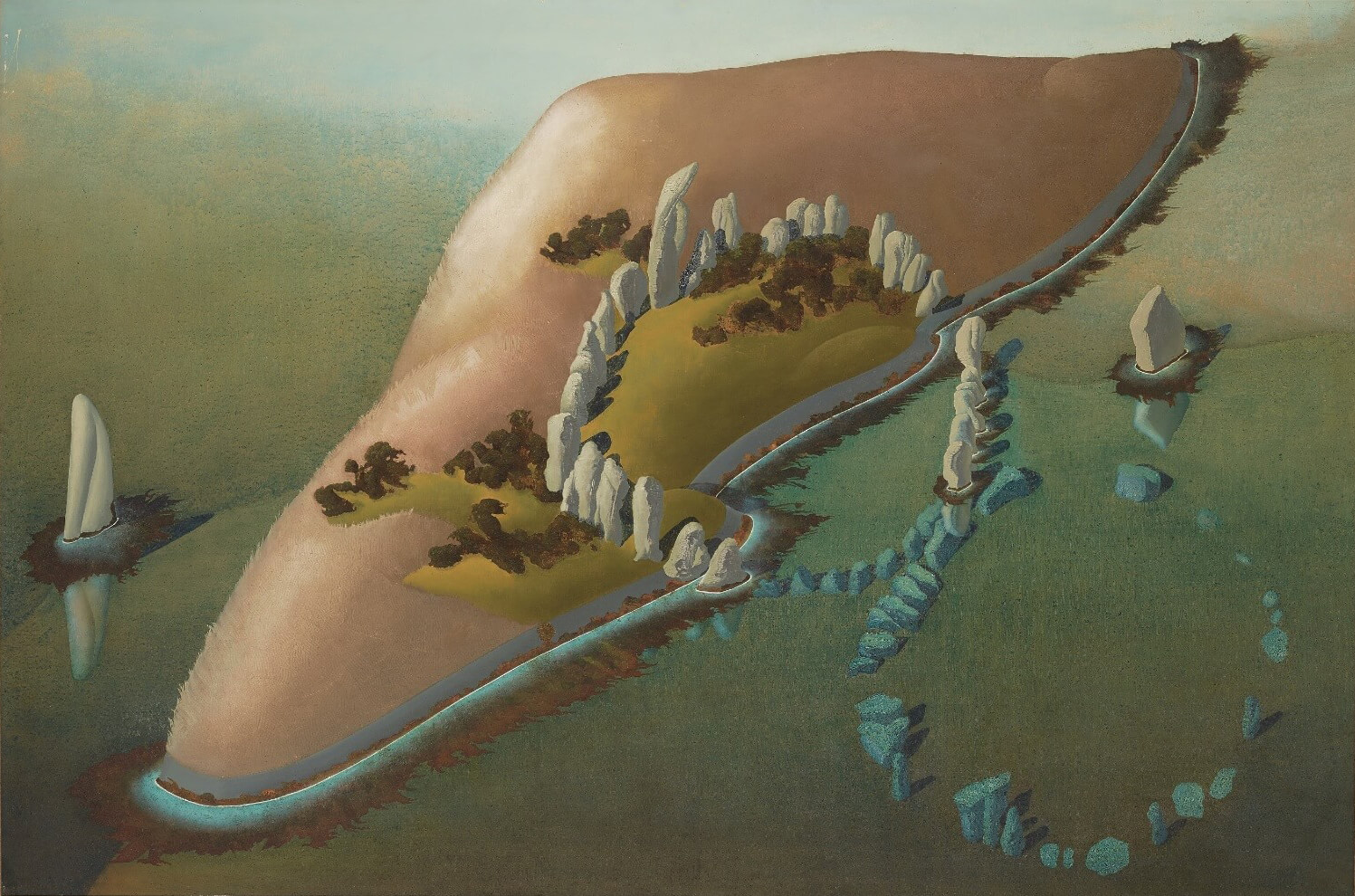

I love them all! But if I had to choose one, I suppose it would be Ithell Colquhoun’s imposing La Cathédrale Engloutie, ca. 1950. The painting was inspired by the stone circles on the islet of Er-Lannic whose ancient monuments are now half-hidden by the waters of the Gulf of Morbihan, Brittany. Colquhoun wrote of ‘the daily immersion of this temple, dedicated to the powers of both sea and earth’, and indeed, it has a powerful, magical aura that is difficult to describe unless you are standing in front of it. There has been a revival of interest in Colquhoun in recent years, thanks to the endeavours of Richard Shillitoe and Amy Hale, and the wonderful news is that Tate are putting on a major retrospective in 2025, and have asked to borrow the RAW works!

It is groundbreaking for its inclusion of over 50 artists, many of whom have rarely been exhibited before. A majority of the works have been sourced from private collections and will therefore be seen by the public for the first time. Also, this is the first exhibition on Women Surrealists EVER in France, which seems very apt as we approach the centenary of Breton’s first Surrealist Manifesto, published in Paris in 1924.

I already wrote a catalogue essay in the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s Surrealism show in 1920 about the British women Surrealists, and I was very happy to be invited to write a text for the Montmartre catalogue placing British women in an international context. These artists, except perhaps for Leonora Carrington, are very little known outside Great Britain and I am excited to see the reaction of the public and the press to the many British works on show.

I can’t recommend the catalogue enough, which is filled with colour reproductions and a host of interesting essays on different themes explored by women surrealists, including, metamorphosis, nature, seduction and femininity, as well as eyes, night, gloves and the journey to abstraction.

That it was a male-dominated movement and that within it women were only ‘femme-enfants’, celestial creatures, muses, sorceresses, erotic objects and femme-fatales. Astonishingly, in The Militant Muse (2017), Whitney Chadwick recalls the prominent British Surrealist Roland Penrose dismissing her plan to write about the women of surrealism: ‘They weren’t artists…of course the women were important, but it was because they were our muses.’. We now know that they were even better artists than their male counterparts (at least I think they were, but then I am biased!). One exciting aspect of Surrealism for me is that it was one of the first movements in which women artists tried to banish the hierarchy between the genders and challenge sexual orientation. Many were lesbians and lovers, others were in relationships with male figures of Surrealism, and many were gender-fluid. But what they all had in common was the inventive ways in which they used their art as a vehicle to eradicate established social paradigms and radically challenge traditional ideas about gender and identity.

I hope, along with our brilliant curator Maudji, to continue building the RAW collection, which will always be available for loans to public collections and museums. On top of that, we hope to continue uplifting and supporting radical contemporary artists through our sponsorship program and the RAW + blog. All of this is tied together by the single goal of giving visibility to censored, marginalised and suppressed voices so that we can play, even a small but vital role, in shaping the way we consider our artistic heritage.