Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

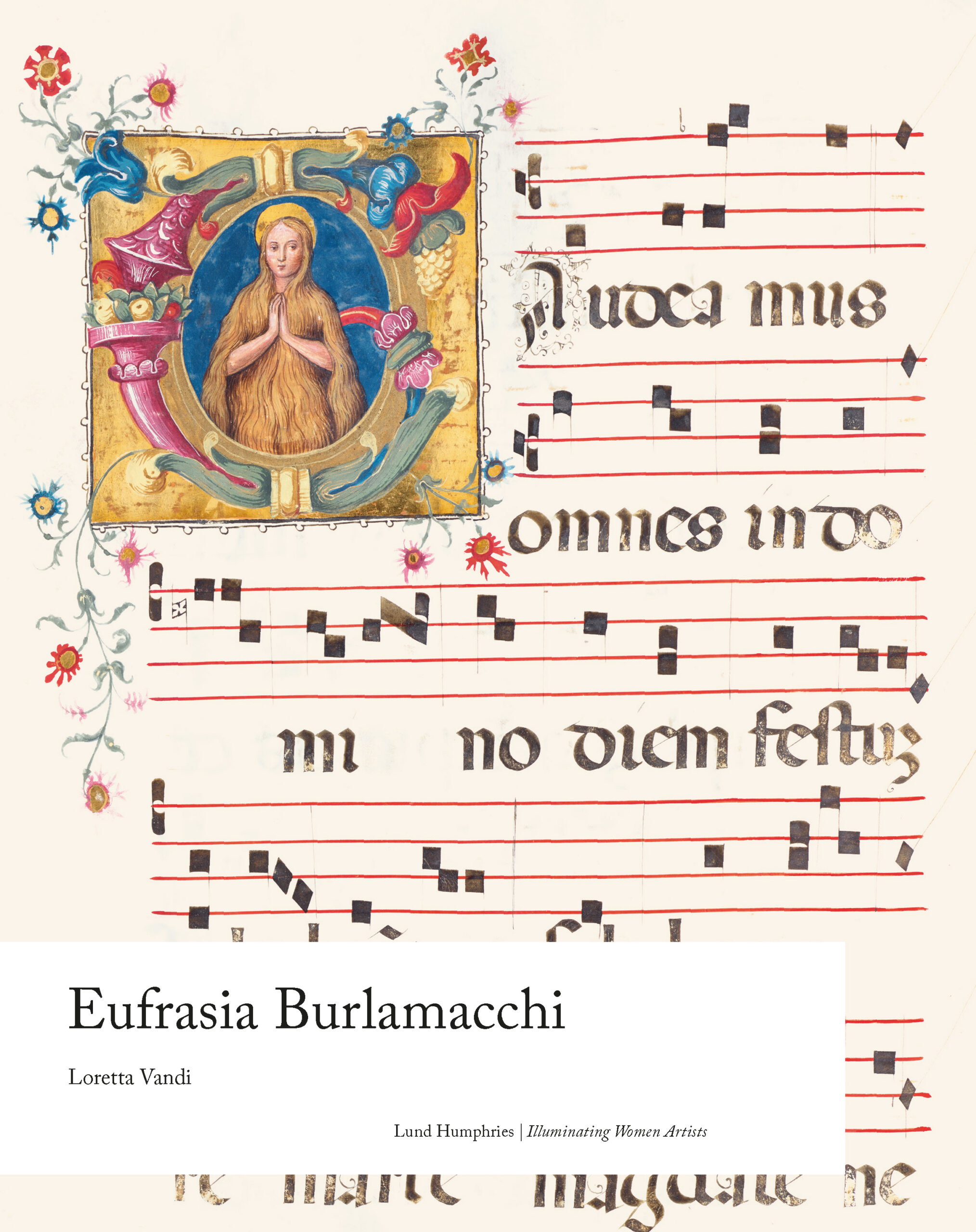

Lund Humphries’ Eufrasia Burlamacchi, penned by Loretta Vandi and set for publication in 2025, arrives at a moment when feminist art history continues its long-overdue reckoning with historical omissions. Part of the Illuminating Women Artists: Renaissance and Baroque series, this monograph presents the first full-length study of a sixteenth-century manuscript illuminator whose artistic labor had already faded from view by the time Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects set the canon in stone.

Vandi’s project is one of retrieval and rehabilitation, positioning Eufrasia not as a footnote in conventual craftsmanship but as a singularly innovative figure whose work, though created within the confines of the cloister, was anything but minor. With sharp analysis and meticulous research, Vandi exposes how the structures of art history have long systemically excluded figures like Eufrasia. Weaving together feminist art history and archival inquiry, she situates her subject at the intersection of gender and conventual creativity. In doing so, Eufrasia Burlamacchi challenges traditional hierarchies of artistic production, interrogating why certain forms of work—particularly those associated with women and religious institutions—have been dismissed as peripheral.

This review considers Vandi’s success in re-contextualizing Eufrasia, examining how she navigated gendered constraints, the paradoxes of conventual life, and the systemic undervaluation of the so-called “minor” arts.

The book begins with chapters depicting Eufrasia’s background – childhood, familial relationships, adolescence years, and womanhood. Born in 1478, Eufrasia Burlamacchi entered the Dominican convent of San Nicolao Novello before co founding the more austere San Domenico in 1502. There, she devoted herself to manuscript illumination, producing exquisite antiphonaries and graduals—texts essential to the liturgical practice of convent life. Rich in intricate ornamentation and luminous color, her work served both devotional and pedagogical functions, embedding artistic excellence within the daily rituals of worship.

Vandi makes a compelling case that Eufrasia’s practice was more than an expression of piety—it was a means of asserting artistic agency in a world that afforded women few opportunities for creative self-expression. The book acutely dismantles the myth of the convent as a passive, cloistered space. Instead, San Domenico emerges as an environment that nurtured artistic ambition and skill— “in the San Domenico convent, the propensity of Eufrasia for art was encouraged, and her responsibility in conveying the correct religious meaning increased with the tasks assigned to her.”

Religious devotion and artistic production are shown to be inseparable, each reinforcing the other. By examining religious traditions and the specific role of art within these spaces, Vandi underscores the importance of assessing artistic production within its social and cultural contexts “to evaluate women artists according to what they produced within their social and cultural environments.”

While Eufrasia Burlamacchi acknowledges the conditions of enclosure that shaped the artist’s life, it does not frame these restrictions as purely limiting. Rather than reinforcing a narrative of artistic suppression, the book takes an exploratory approach, examining the ways in which Eufrasia cultivated a multifaceted artistic practice within the preconditions of the convent. By emphasising how she adapted, innovated, and thrived within the structures of religious life, Vandi reframes the convent not as a site of erasure, but as a space where female agency could manifest in complex and meaningful ways. This perspective resists one-dimensional readings of conventual spaces as inherently oppressive, offering a richer, more nuanced view of women’s artistic production.

Then there is the matter of medium. If painting and sculpture were seen as the highest forms of artistic genius, manuscript illumination was relegated to the realm of the decorative—intricate, ornamental, and, crucially, feminized. Vandi critiques this hierarchy, demonstrating how Eufrasia’s work, with its meticulous detail and innovative use of color, rivaled that of professional illuminators outside the convent walls. She lays bare the gendered biases that have shaped the art historical canon, arguing “If painting alone allows women artists to vie with men, degrading other artistic productions to ‘servility’ to the ‘major arts,’ then no art history could be rewritten.”

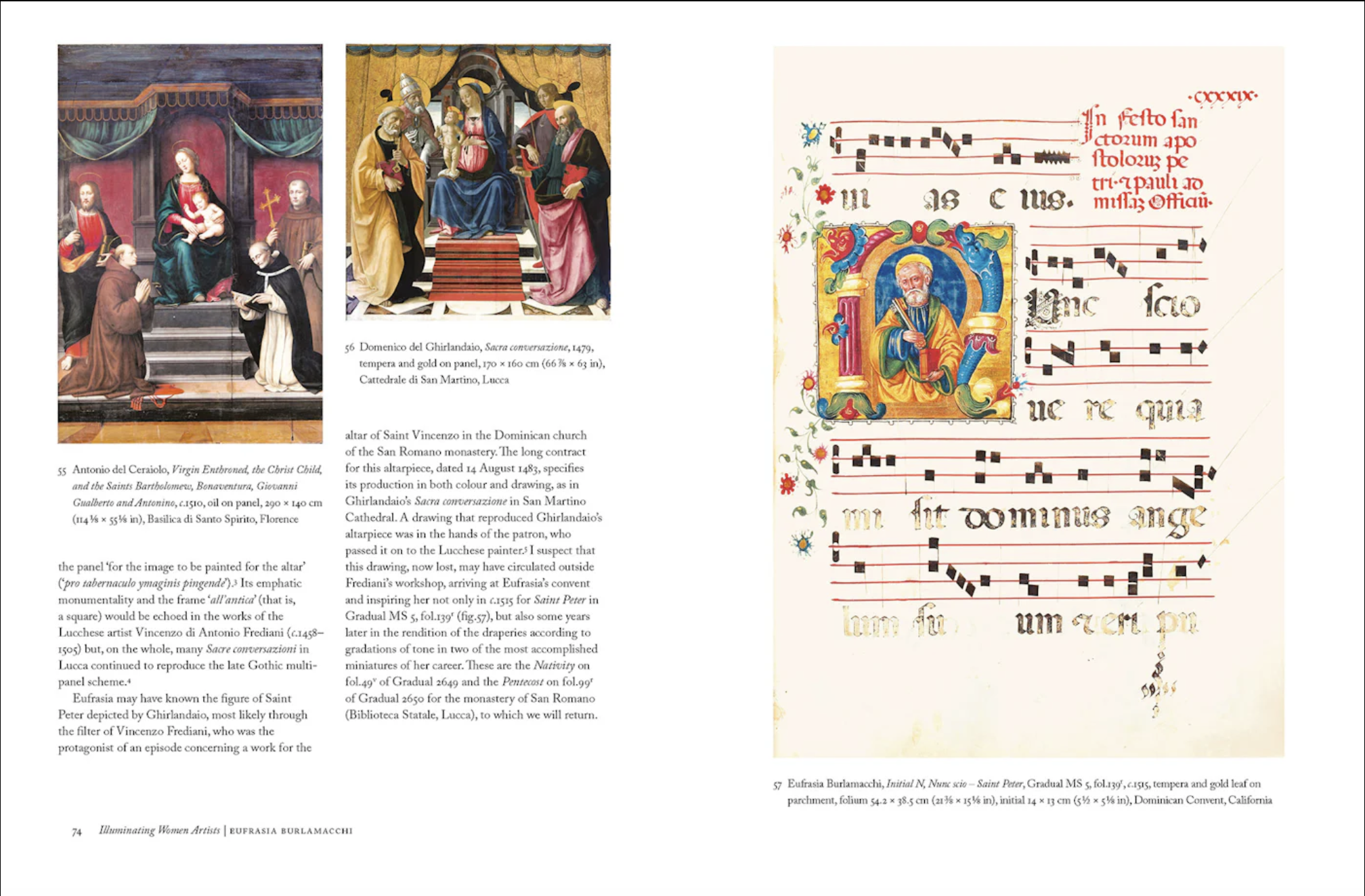

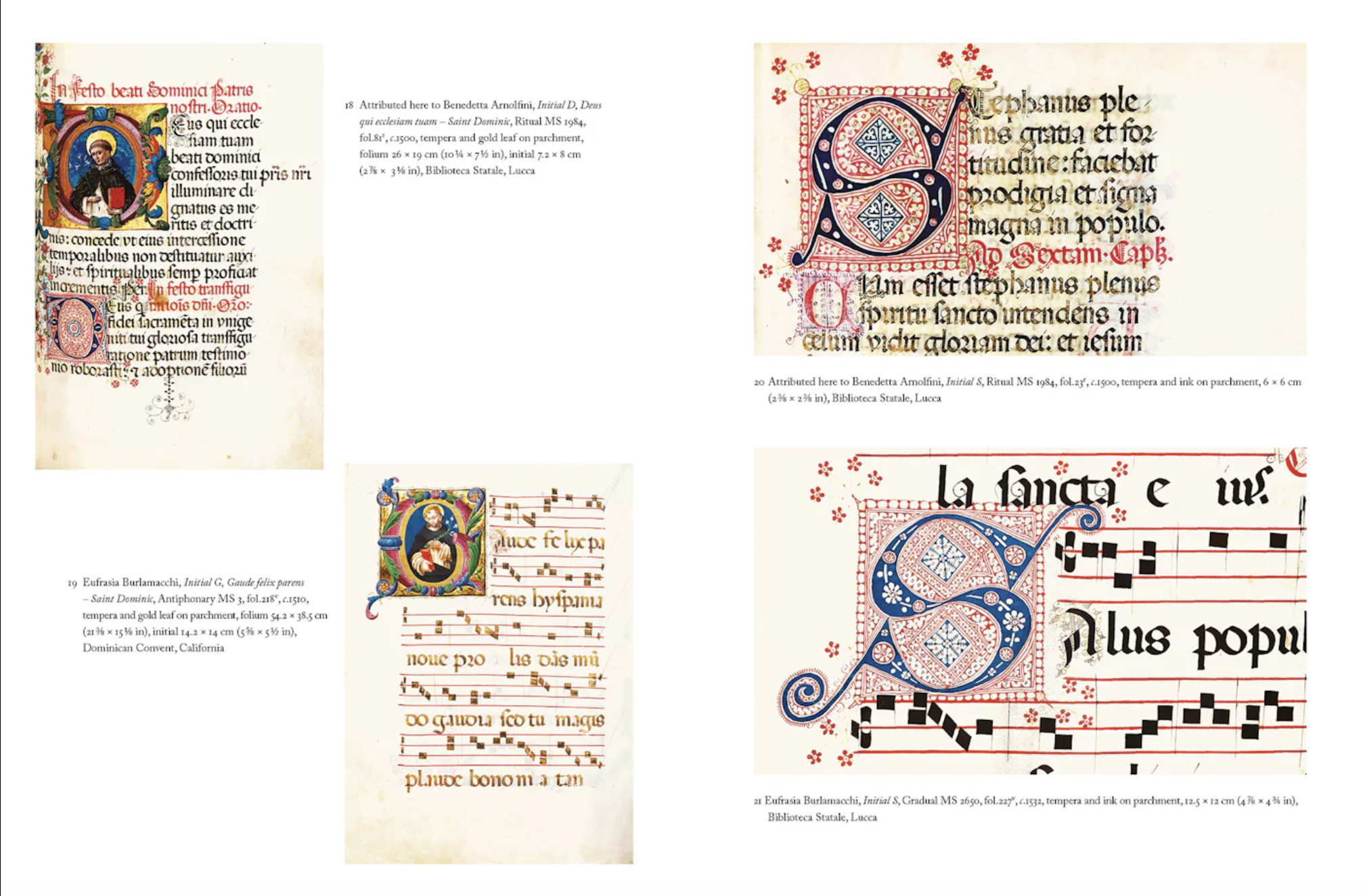

Eufrasia’s miniatures challenge these assumptions. Her illuminations—dense with acanthus leaves, grotesques, and jewel-toned embellishments—showcase a sophisticated understanding of spatial composition and chromatic harmony. Vandi frames her illumination as a nuanced product of both religious function and formal training. As she explains: Illumination was indeed freer from naturalistic constraints, from the direct study of anatomy and natural light, than painting, and especially in ornament one could invent and develop forms and choose colours with no limitation imposed by the subject and composition. In her eclectic works, Eufrasia treated the ‘architectural’ elements of the letters—the vertical, horizontal, oblique and semicircular bars—according to various metamorphoses. The pliability of this ‘architecture’ to the expressive needs of religious meaning is Eufrasia’s most original contribution to Renaissance ornament and, accordingly, to the history of Renaissance illumination.

This call for reassessment underscores a broader feminist intervention: expanding the parameters of artistic value to encompass media long dismissed as ancillary.

Yet for all her artistic prowess, Eufrasia’s work has been largely neglected and forgotten. No Vasari came to record her achievements. No grand commissions ensured her legacy. Her illuminations, embedded within the fabric of convent life, was seen as a mere extension of religious duty rather than a personal artistic statement.

Vandi sharply problematizes how “[n]o artistic biography of Eufrasia Burlamacchi exists, despite her status as a highly talented early modern artist”; that we are only now reassessing her contributions speaks volumes about the biases embedded in the historical record. Yet, as Vandi makes clear, the issue is not merely one of oversight but of systemic undervaluation. Artistic labor performed by women, particularly in convents, was often framed as devotional rather than professional, stripping it of the prestige accorded to male contemporaries. Here, Eufrasia Burlamacchi serves as both a corrective and a provocation, urging scholars to continue dismantling the structures that have long determined artistic significance.

Vandi’s Eufrasia Burlamacchi is a significant addition to feminist art history, not only for its meticulous reconstruction of a nearly lost career but for its broader critique of how art history is written—and who gets written out. The book challenges readers to reconsider the boundaries of artistic achievement, questioning whether we have been looking in the wrong places all along.

Eufrasia Burlamacchi by Loretta Vandi is available for pre-order at https://www.lundhumphries.com/products/eufrasia-burlamacchi