Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

As one of the most radical and influential American artists of the 20th century, Diane Arbus (1923-1971) was known for her intimate and unconventional portraits. While she was still championed in her time – in 1963, she was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship – and was something of a legend in photography circles, her work was only included in a small number of group shows. A year after her death, the Venice Biennale included ten huge photographs by her which, according to the New York Times, were “the overwhelming sensation of the Pavilion”. Soon afterwards, a large retrospective of her work opened at at the Museum of Modern Art in New-York City, which attracted 250,000 visitors.

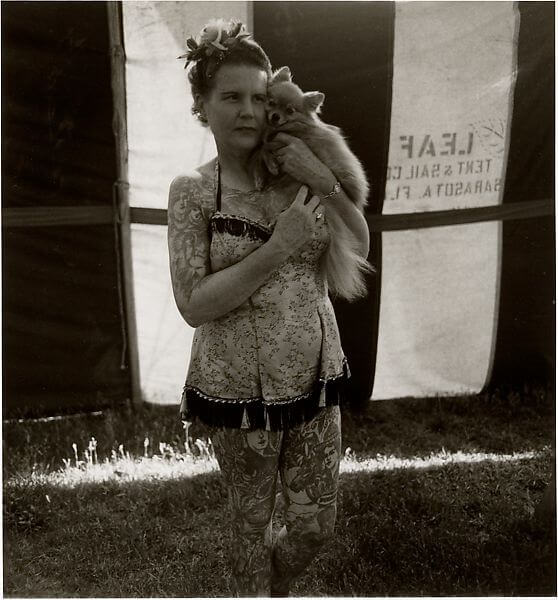

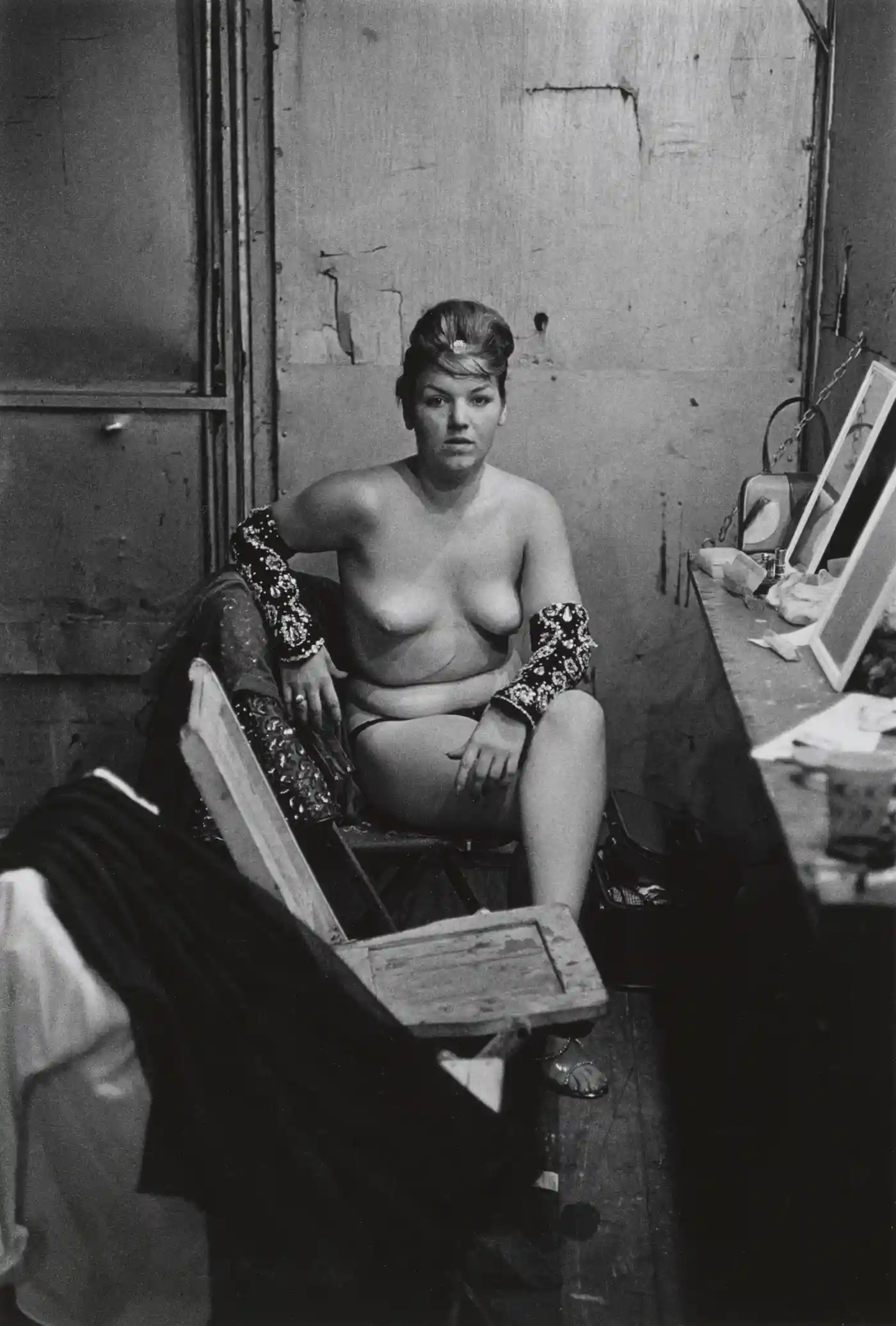

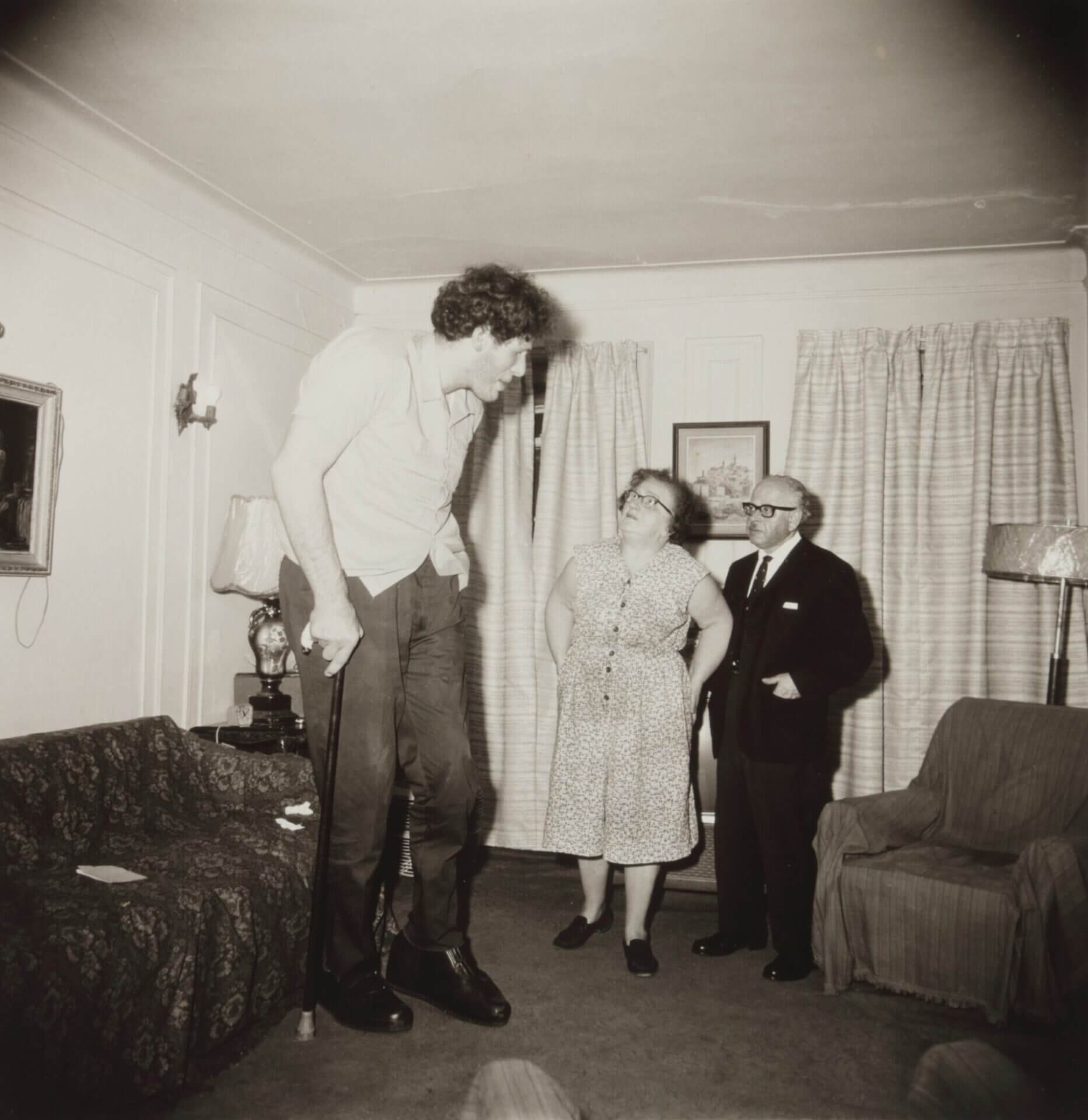

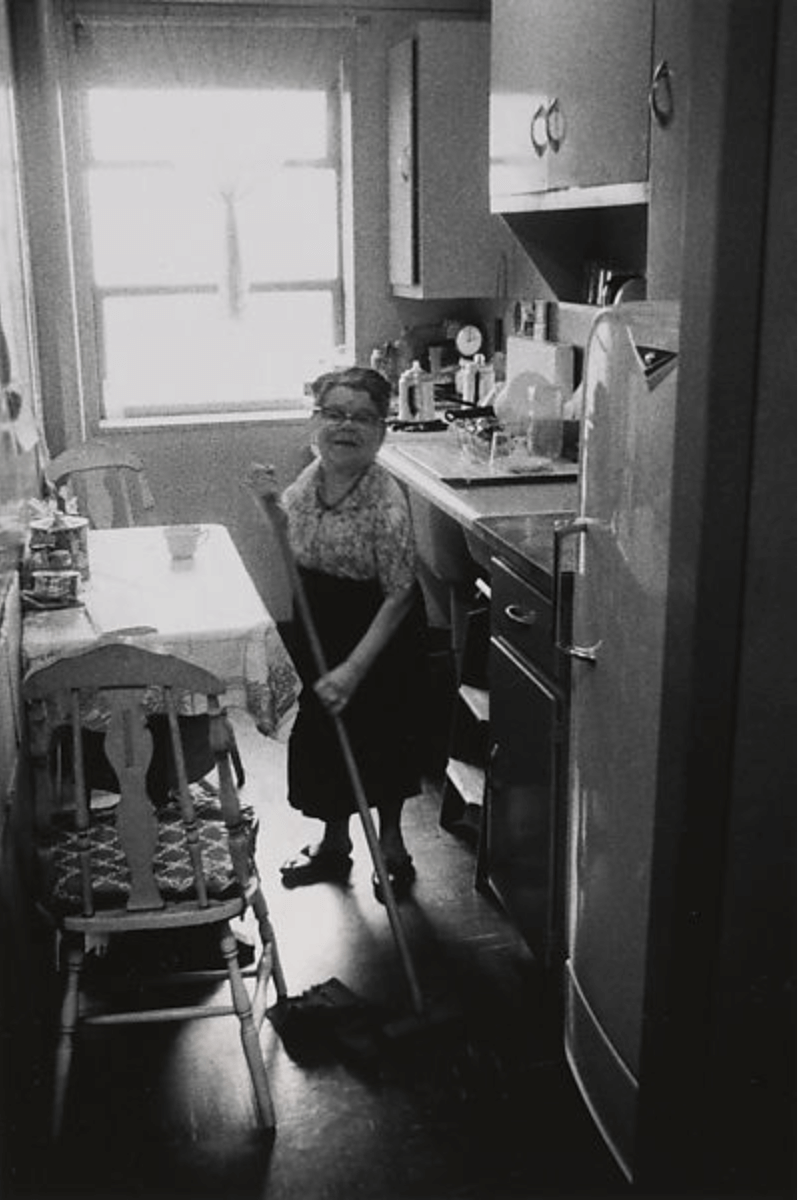

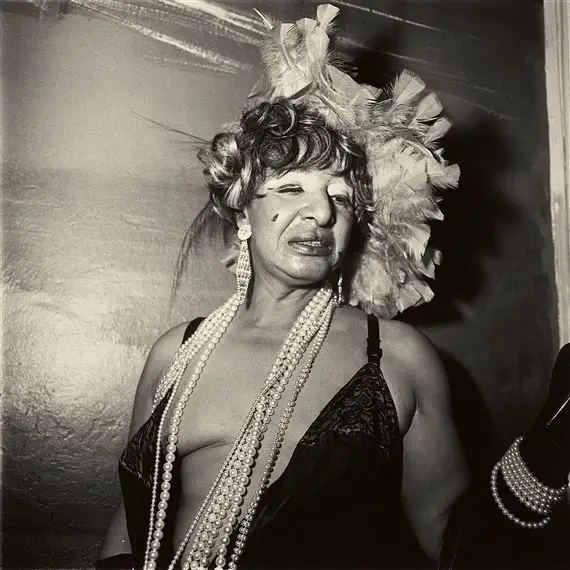

A 2003 effort in reassessing her work, ‘Revelations’ (Random House) – spanning her entire career – has shown Arbus to be not only a pioneer of portraiture but also an advocate of the ‘other’, by representing the most marginalised groups such as people with dwarfism, transvestites, giants, strippers, carnival performers, nudists, elderly couples, and middle-class families. Her work was marked by constant questioning of identity, gender, bodies, and ageing: she was determined to reveal what others had been taught to turn their backs on. Her excited appreciation of whoever struck her as extraordinary allowed her to gain entry to a female impersonator’s boudoir, a dwarf ’s hotel room and countless other places that would have been closed to a less persistent, less appealing photographer. Once she obtained permission to take pictures, she might spend hours, even days shooting her subjects again and again and again. Her subjects often became collaborators in the process of creation, sometimes over many years. For example, the Mexican dwarf she photographed in a hotel room in 1960 was still appearing in her photographs ten years later. And she first photographed Eddie Carmel, whom she called the Jewish giant, with his parents in 1960, ten years before she at last captured the portrait she had been seeking.

However, her work was not always appreciated – being a champion of anything “too frightening”, or “too ugly” for anyone else to look on, many accused her of being condescending towards her subjects and also of voyeurism. American philosopher and political activist Susan Sontag for example, called her portraits of “assorted monsters and border-line cases. . . . anti-humanist.” Arbus’ work, Sontag continued, “shows people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive, but it does not arouse any compassionate feelings.” Another critic of her work, Jed Perl wrote in The New Republic, “Arbus is one of those devious bohemians, who celebrate other people’s eccentricities and are all the while aggrandising their own narcissistically pessimistic view of the world.”

In the 1960s & 70s, people hadn’t seen an unambiguous picture of a man in curlers with long fingernails smoking a cigarette, and at the time it seemed confrontational. Looking at her photographs from a 21st century perspective, they seem more elegiac and empathetic than threatening.

A reader of Freud, Nietzsche and James Frazer’s treatise on religion and mythology, Arbus saw the subjects she photographed both as fascinating real-life personages and as mythic figures. Through them she found a way to photograph people and places that were far removed from her own background. “I have learned to get past the door, from the outside to the inside,” she wrote in a 1965 fellowship application. “One milieu leads to another. I want to be able to follow.”. Today, there is new appreciation for her work as she continues to inspire urban street culture as well as popular culture.“I have never been moved by any other artist as I have been by Arbus,” said Jeff Rosenheim, specialist in American photography at MOMA. “Her pictures have this power that is the exact correlation of the intimate relation she must have had with her subjects. They forever affect the way you look at the world. Whether Arbus is photographing a tattooed man, a drag queen or a wailing baby, the more we look at her pictures, the more we feel they are looking back at us”. Sandra S. Phillips, American writer, and curator of Photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art said, “She was a great humanist photographer who was at the forefront of what has become recognized as a new kind of photographic art.”

‘Untitled (I)’ (c.1970)

‘Untitled (I)’ (c.1970)Between 1954 and her suicide in 1971, Diane Arbus took more than 150,000 photographs, producing a body of work whose style and content have secured her a place as one of the most significant artists of the 20th century.