Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

I first started researching Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) way back in the year 2000, while working as a Lecturer at the University of Exeter’s Institute of Cornish Studies. Back then, almost no one knew who she was. At that stage she was a curious footnote of British Surrealism, one of the so-called “lost women Surrealists”. If someone at that stage was familiar with her, perhaps they had seen her landmark piece Scylla held by the Tate, or, more likely, they had read her early psychographic study of Cornwall, The Living Stones, chronicling some of the strange, magical features of mid-century Celtic Cornwall in a way that continues to strike a resonant chord with people who love that stirring, rocky peninsula. Colquhoun’s paintings were not widely known or even available, with the bulk of her visual archives held at the National Trust until 2019, nearly inaccessible to researchers or the general public. When her paintings did, occasionally, come up at auction, they were hardly big-ticket items. Even considered within the history of Cornwall’s famed art communities, Colquhoun was an odd outlier, certainly not a Modernist, and not part of the cadre of Surrealists who had found inspiration there during a visit in 1937. She had a historical presence, yet was more of an unquiet shade, a haunting waiting to be conjured into full rematerialization.

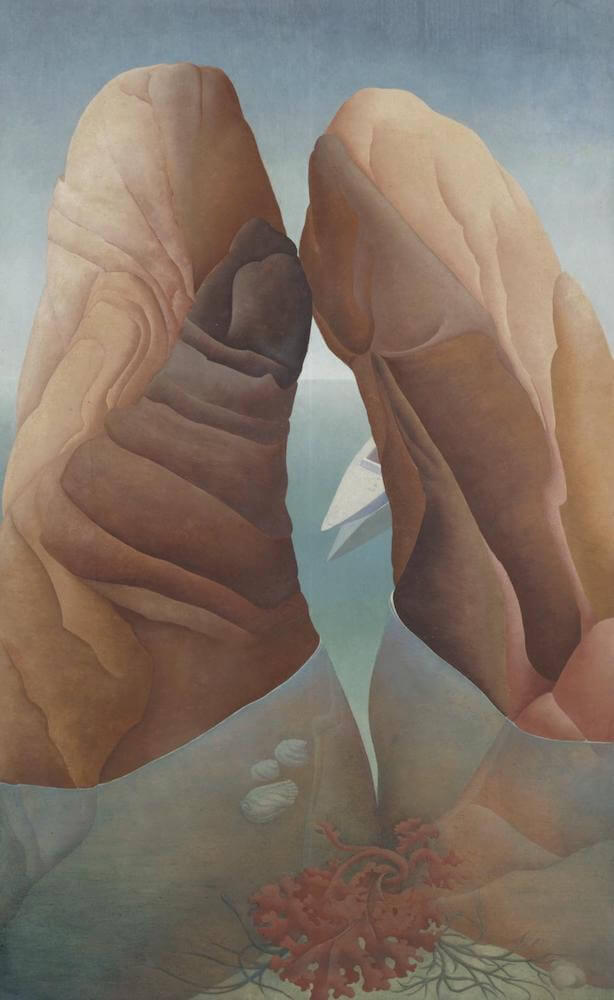

Ithell Colquhoun – Scylla (1938)

Oh, how times have changed. A recent auction saw Colquhoun’s 1947 decalcomania “Still Water” fetch a record £53,200, a whopping over 700% above the estimated sale price, which would have been utterly unheard of a decade ago. For me, the moment I most profoundly felt the shift was when I was giving a lecture about Colquhoun’s work in Boston in 2019, a full eighteen months before my biography of Colquhoun was published by Strange Attractor Press. The house was packed, and when the title of the talk was announced, the room erupted, not for me, but for her. The drop of Colquhoun’s name got a standing ovation. Her genius had escaped the unseen dimensions and had diffused outward to this eager audience. Her presence hung in the air as offerings of applause and gratitude nurtured the canny spirit, who had so wisely chosen her time for reemergence.

Ithell Colquhoun – Still Water (1947)

Since my first encounter with Ithell Colquhoun I knew I was dealing with a woman of remarkable horse power. She was a wild talent and amazing intellect, prolific with words and a paint brush, fiercely unstoppable and uncompromising who, like so many, found the appreciation she chased to be elusive. She was simply so ahead of her time. As we know, uncompromising women frequently struggle mightily against tough head winds, and while she had definitely sought and craved recognition and success it was always on her own terms, which unfortunately limited the extent of her results. While she definitely maintained her integrity, she also did not yield to the marketplace or modify her work to make it more accessible or palatable. She certainly stood in her own way while she was alive, but in terms of her legacy maybe she made the right call. In many ways, a recent convergence of cultural trends was almost designed for her historical arrival, the more relevant of which are the recent revival of interest in Surrealism, a new focus on the history of women artists and a reconsideration of the role of magic and the occult in Western culture.

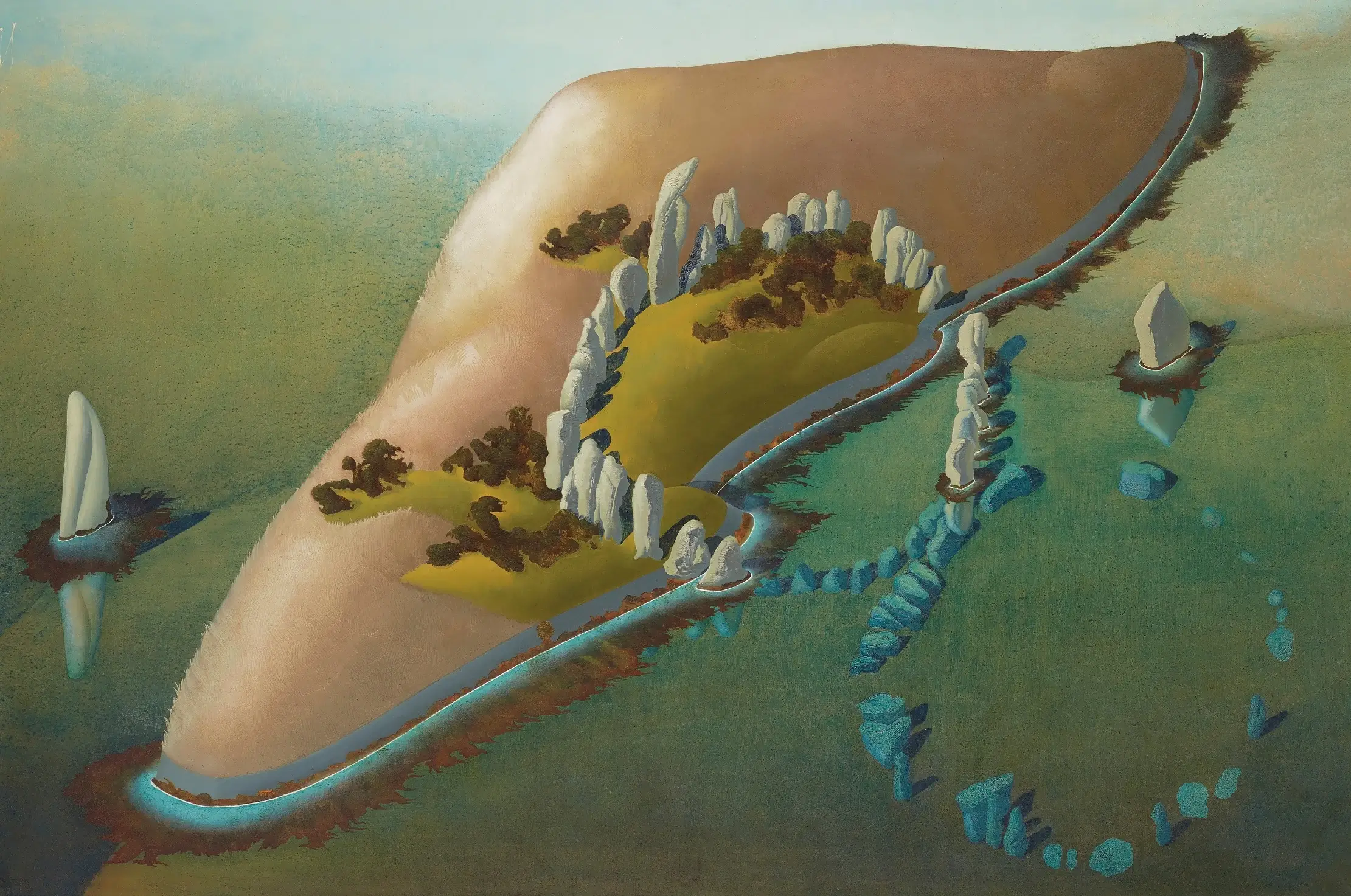

Ithell Colquhoun – Alcove II (1948)

Certainly, international Surrealism is finding new audiences. While I am generally reticent to glibly attribute “troubled times” to an increased interest in enchantment, I might concede that the general turmoil of the world in the past five years has created fertile soil for the reception of a movement promoting liberation, collaboration, the irrational and the power of dreams. Colquhoun’s emergence is certainly part of this wider celebration, yet even within Surrealism, Colquhoun’s works seem to stand apart. Many of her Surrealist pieces, especially her automatisms, are not immediately approachable. They are deeply informed by occult principles, and do not feature the strange and delightful dream imagery of many of the other women Surrealists currently dominating the artistic landscape. Colquhoun’s work invites you in differently, there is often no immediate narrative, nothing to tether the viewer to an interpretation. And her admirers are often as drawn to her process as they are to the product, with people finding deep resonance in her connections with the numinous and how other dimensions informed her artistic practice.

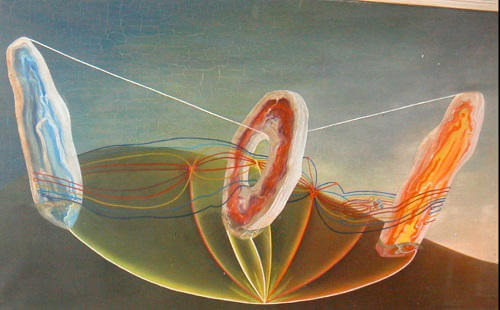

Ithell Colquhoun- Gouffres Amers (1939)

Additionally, there is, as the work of RAW demonstrates, a necessary and urgent interest in rediscovering the contributions and lives of women artists who have been consistently neglected, sidelined, misunderstood and unappreciated. The wider project is greater than amplifying forgotten voices and talents, for we must also undo the linear narratives of (often White) male genius that dominate all history, not only that of art. As we know, when we tell the stories of women, the entire framework of our understanding changes. The recent reconsiderations of the history of abstraction stemming from our awareness of the work of Hilma af Klint, Georgiana Houghton and other spiritually inspired artists are but one example and the rewriting of art history will be an ongoing process. Women’s engagement with magic and esotericism also forces a reassessment of that male dominated history as well, and people are hungry for those stories.

Ithell Colquhoun – The Sunset Birth (1942)

Crucially, we are currently seeing a reframing of magic and the occult in Western art and culture more broadly, and that trend clearly impacts the context for Colquhoun’s warmer reception. For most of the twentieth century, the role of the occult in art and literature was marginalized, and often ridiculed, set against a largely false narrative about the dominance of rationalism and disenchantment that was believed to have fully engulfed a naïvely monolithically conceived “West”. Yet thinkers of the past decade are starting to accept the ubiquity of esotericism and occult belief and practice, sitting aside both conventional religiosity and also even secularity and various registers of atheism. Just as in the rest of the world, we are coming to accept that people’s spiritual expressions are complex, inconsistent and dynamic, and that magic is always in the background and sometimes right in front of us. This is opening the way for more interesting and nuanced revelations about the multifaced ways in which the occult and ideas about magic have impacted every facet of Western life, from art, literature, architecture, politics and even economics.

Ithell Colquhoun – The Sunken Cathedral (1952)

Ithell Colquhoun sits at the crossroads of these trends. A deeply magical woman, a thinker and irrepressible artist whose every moment was dedicated to understanding and expressing the hidden fabric of the universe. I believe she is just one of the women the world has been waiting to hear about, to know they existed instead of just hoping or wishing they did. It is just so beautiful to me, in this moment, that Colquhoun no longer has to censor herself, to convince anyone of her relevance or her greatness. I am certain that her spirit is being well fed and she is loving it.

Ithell Colquhoun – Head (Self-Portrait), (1931)

Text by Amy Hale (Anthropologist, Folklorist and Biographer of Colquhoun)