Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

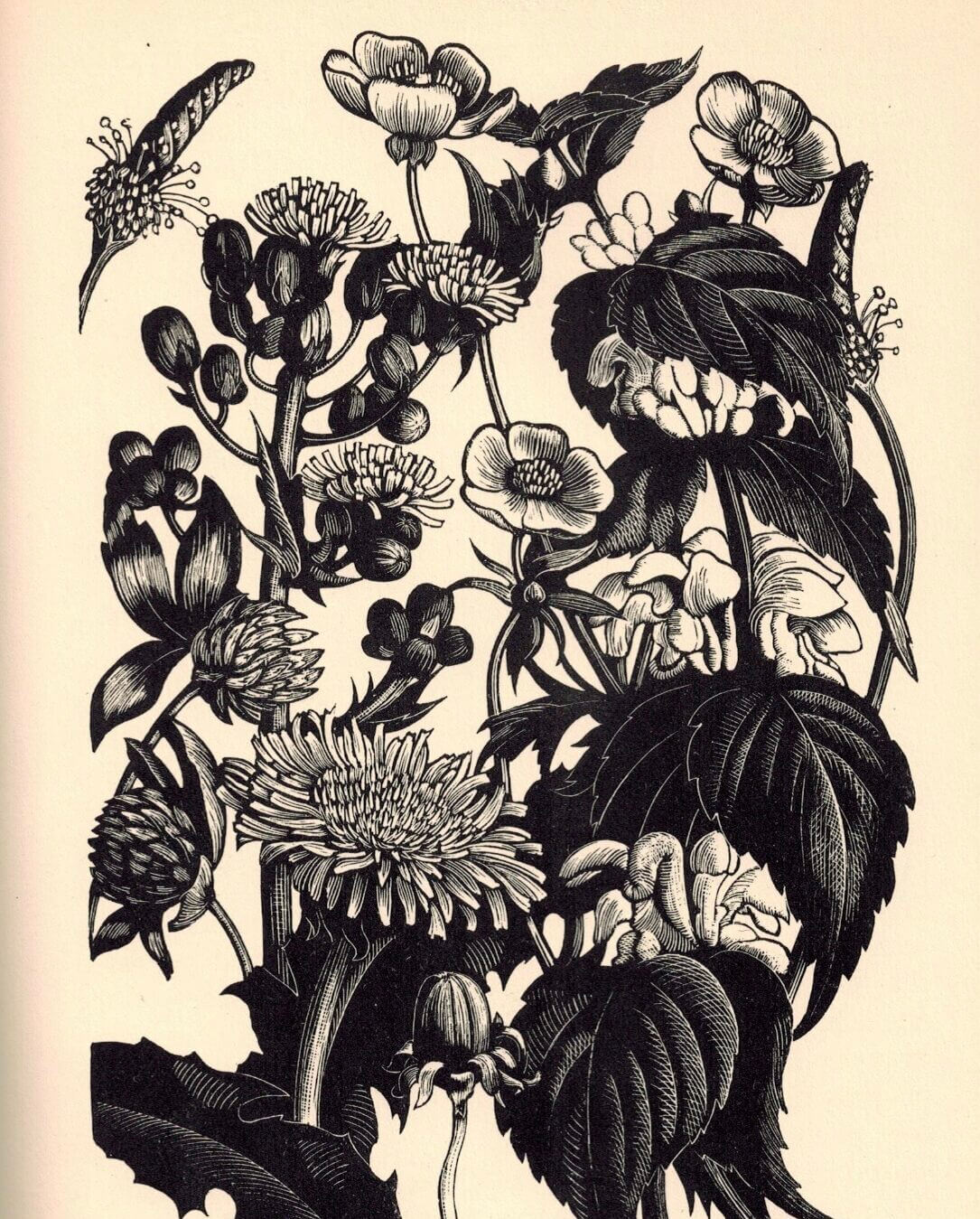

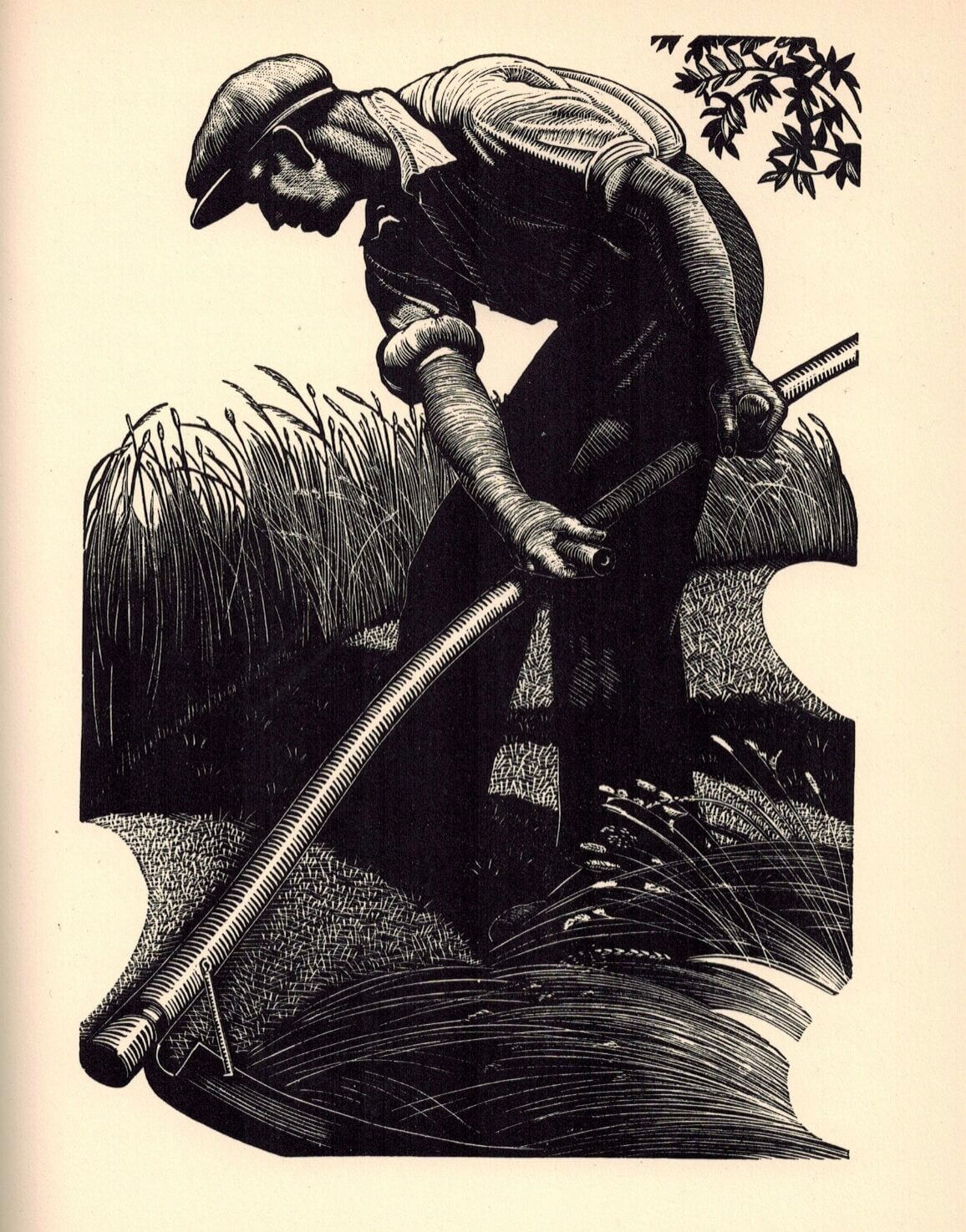

The English artist Clare Leighton (1898-1989) helped transform traditional white line wood engraving into a radically democratic art when she published Four Hedges: A Gardener’s Chronicle with the leftist London publisher Victor Gollancz. The year was 1935 and crises of unemployment, hunger, industrial unrest and fascist threat claimed the headlines. Ordinary citizens from all classes sought solace in nature; when they were not rambling, birding or gardening, they were reading books about the countryside. Four Hedges is Leighton’s autobiographical account of the year she spent creating a garden on what had been an untilled quadrangle of pastureland in the Chilterns. Illustrating her first-person documentary with eighty-eight exquisitely designed and executed wood engravings of everything from spades and scythes to snapdragons, raspberries and snails, Leighton remade with her publisher’s help the conservative clichés of the period’s countryside books. If we read Leighton’s wood engravings as part of a total visual project of countryside living, printing and being, Four Hedges reveals itself and its creator as ripe for feminist recovery. In black and white, the shades of truth and fair dealing, it contributes to the period’s progressive print culture. It celebrated women and rural workers even as its words and illustrations were lost within an art and literary history preoccupied with the masculine industrial emergencies of the devil’s decade.

A 1923 graduate of The Slade School of Fine Art who learned wood engraving with Noel Rooke at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts, Leighton was the first woman to write an instructional book on wood engraving. Her Wood-Engravings and Woodcuts appeared in 1932 in The Studio’s ‘How to Do It’ series. Other women artists at the forefront of the 1930s wood engraving revival included Gwen Raverat, Agnes Miller Parker, Gertrude Hermes, Gwenda Morgan and Joan Hassall. This flowering of female talent may represent the first instance in modern history when women artists were hailed by mainstream critics as leaders of an arts movement. Yet without the visionary mediations of male trade publishers who discovered in the conditions of Depression-era publishing opportunity for advancing wood engraving as a popular art, wood engraving might have remained a form of illustration reserved for the very few, reproduced in the expensive limited editions of private presses.

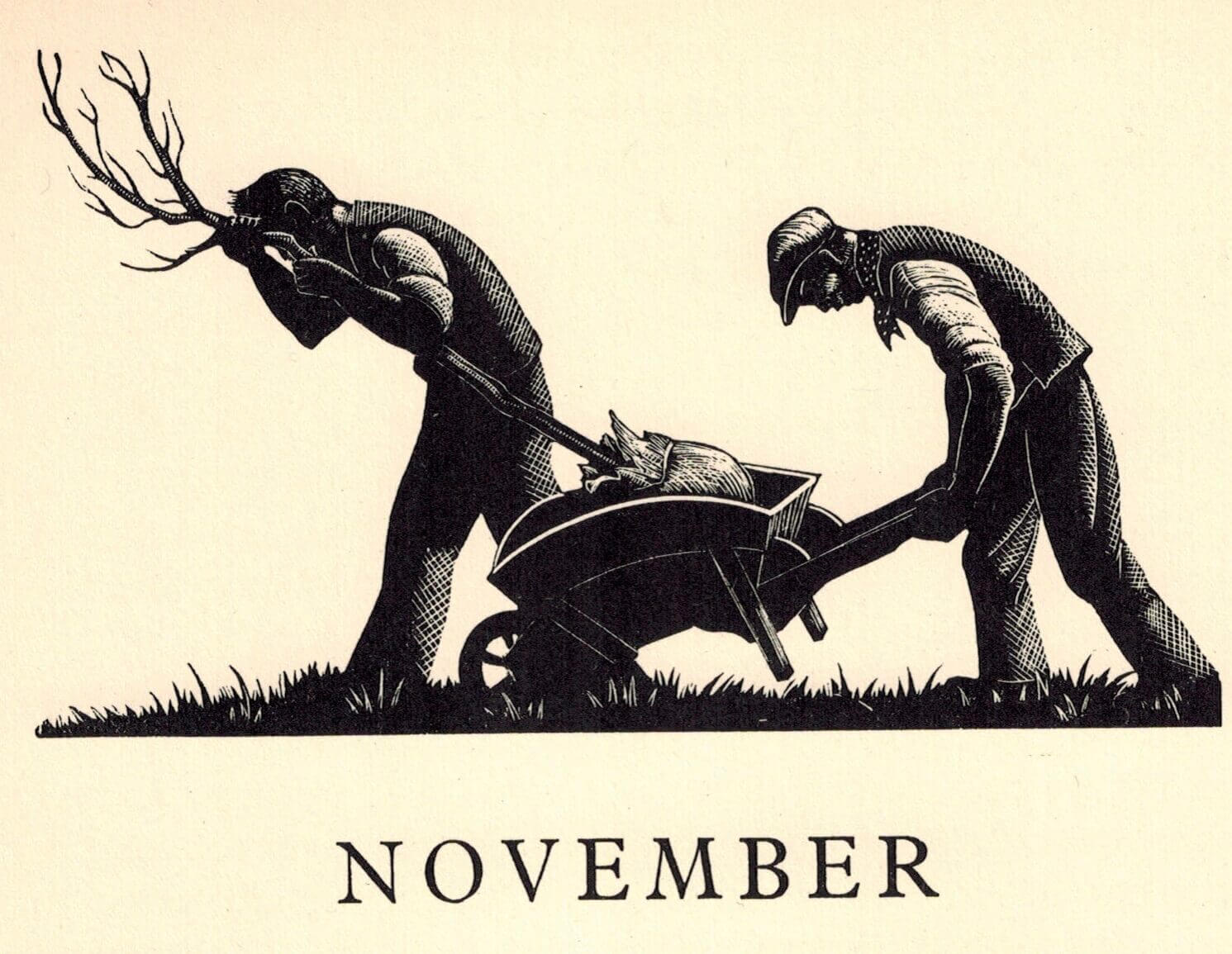

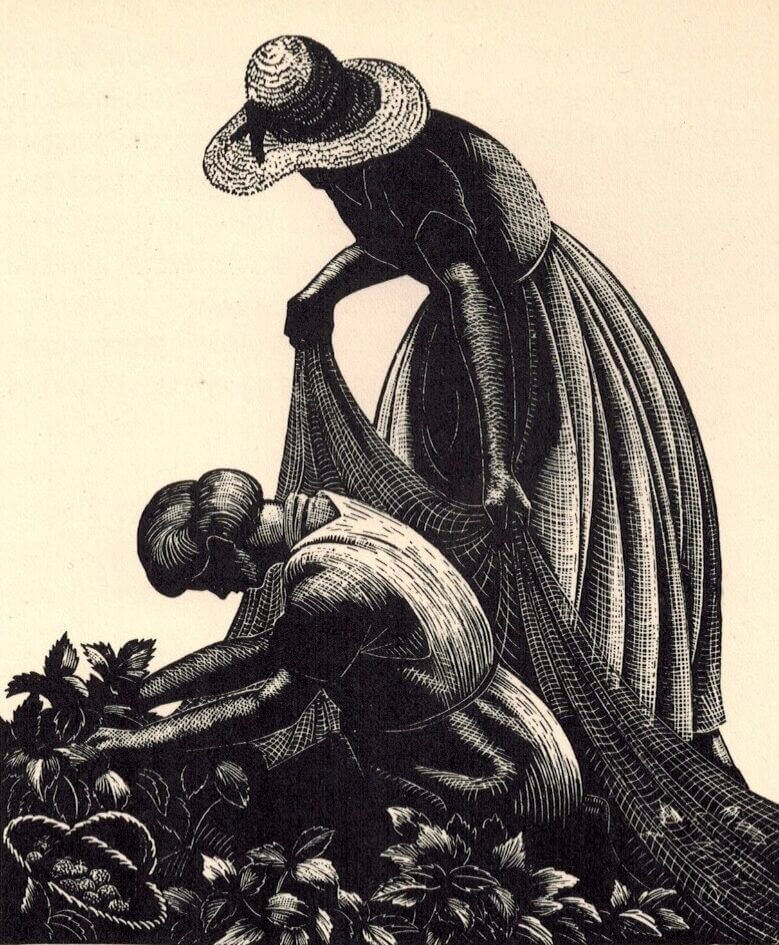

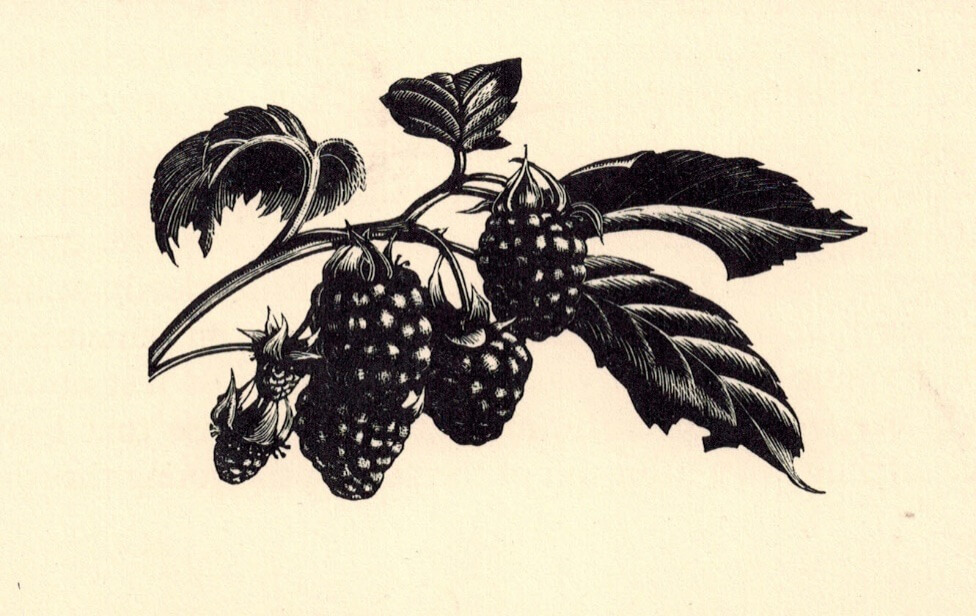

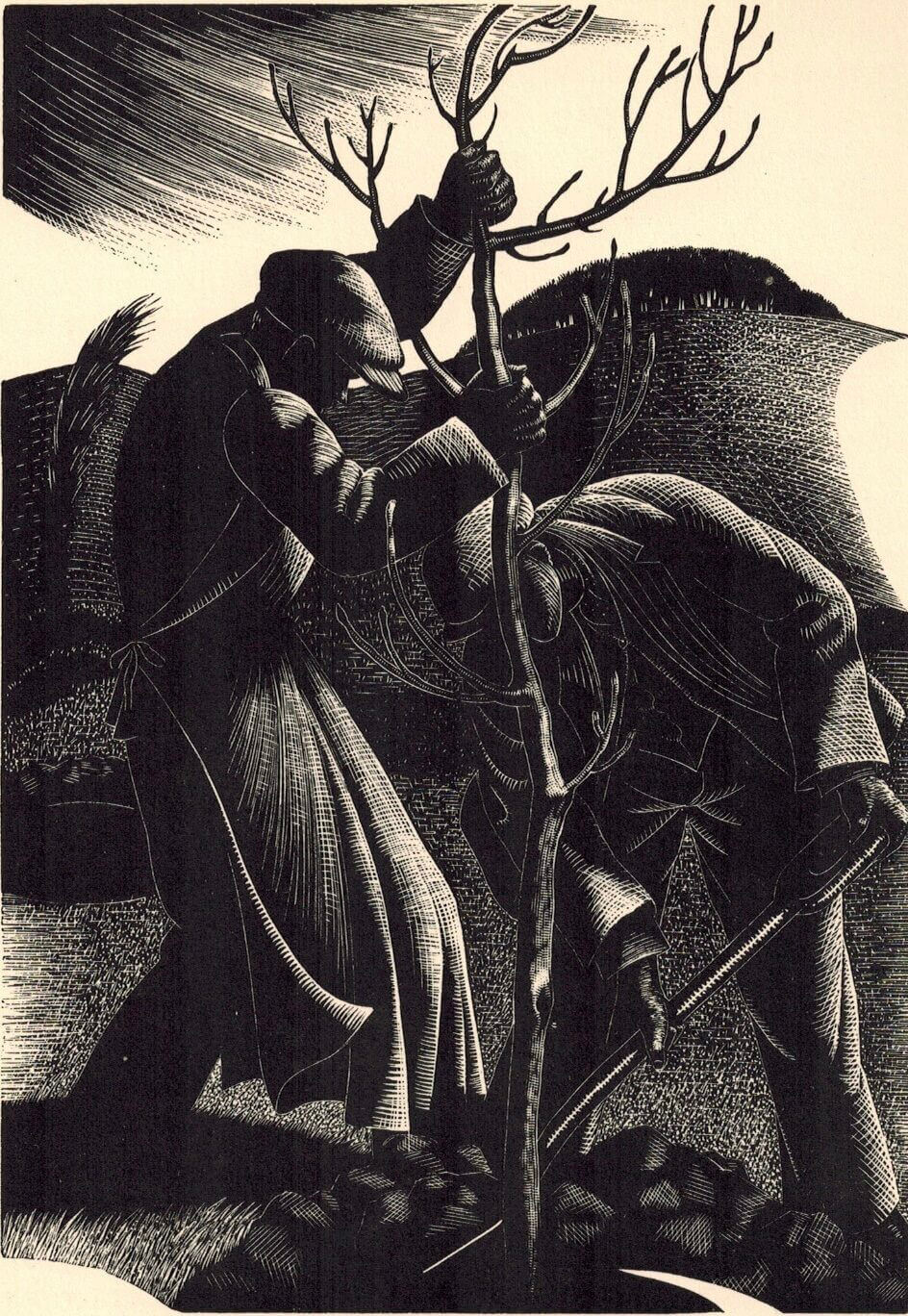

Leighton’s subjects as well as her materials, methods and reproductive medium of illustrated trade books, endorsed and extended the Socialist people’s politics of her publisher. ‘Transplanting Walnut Tree’, for example, represents the sheer physical work of creating a garden and then recreating it through art. We see two men moving from right to left, bending away from the blasts of November winds. The image communicates through the taut curves of each man’s back their equality in shared labour. The first figure, gripping the young tree, is Noel. The second, pushing the wheelbarrow, is the hired gardener, Alf. Leighton is not in the picture, even as her narrative indicates she was working alongside the men, breaking up the solid chalk beneath the earth with an iron bar. Her absence from the picture highlights her presence in the narrative, which depends on the paradoxically invisible and visible work of the woman artist. For no matter how pristine and empty the background of Leighton’s wood engravings of strawberries, broad beans and blackbirds, somewhere there is the artist, observing, sketching, working with pencil and paper in preparation for her work of engraving on wood.

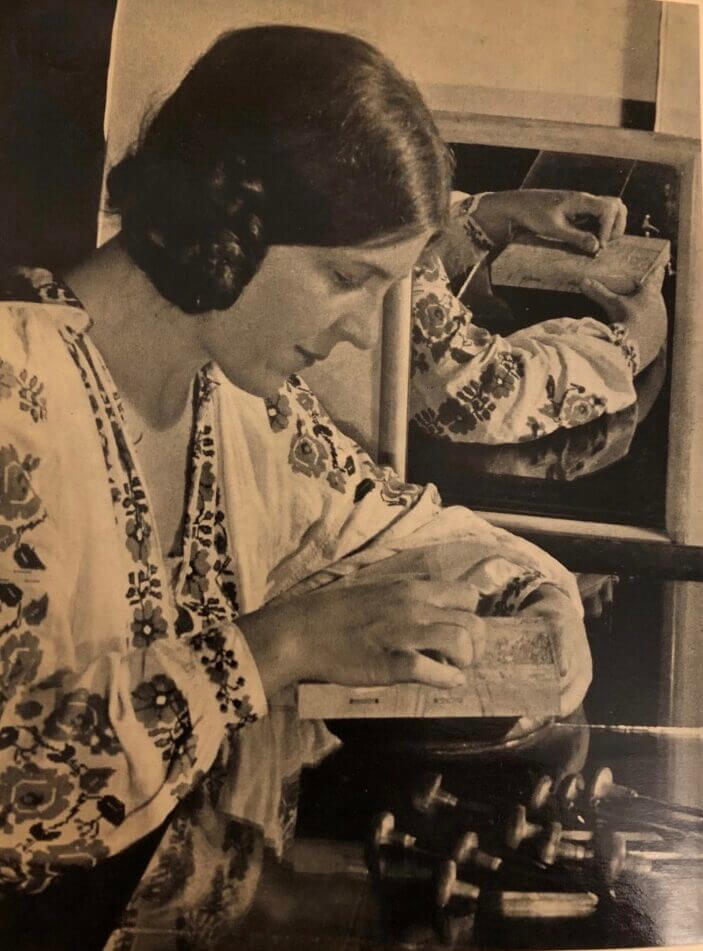

The rural subjects of Leighton’s engravings exist as reversed images printed from small engraved and inked boxwood blocks that, once secured in a chase with metal type, could produce tens- or hundreds of thousands of prints that would be bound up as pages of pretty books for common people. What would have taken Leighton hours to design and execute, working with simple steel tools, a sand-filled leather bag and a globe lamp set upon the kitchen table, would have taken modern printing presses just seconds to reproduce. Leighton’s wood engravings often struck people as old-fashioned, their white lines on black recalling rural scenes engraved by the eighteenth-century artist and print innovator Thomas Bewick. But every illustration in her 1930s countryside books reflects Leighton’s modern vision and gendered experience in a world still largely closed to professional women artists and writers. It was Gollancz who realized that the old-fashioned appeals of Leighton’s wood engravings of garden plants and country life were well suited to modern trade books that could advance a progressive social vision. With his knowledge of cutting-edge print technologies, Gollancz achieved with his Leighton commissions the decade’s highest quality prints in any mass-produced book offered to ordinary readers at reasonable cost.

There were many sources of Leighton’s success: her mother, Marie Connor Leighton, a prolific romance novelist who earned the family’s living through her art; her father Robert Leighton who wrote wild west novels and painted pictures; her uncle Jack Leighton who took her on sketching tours of Europe during her teenaged years; her older brother Roland Leighton who was killed in the trenches and then immortalized in Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth (1933); and perhaps especially, her aunt Sarah Leighton of whom Leighton wrote, ‘She was the first person to show me love. . . . [I]n me she placed the hope that I might create those things that she had not been able to do’ (qtd. in David Leighton, ‘Family Foundations’, p. 50). Yet it was Victor Gollancz with his vision of fine art for the masses, who made possible Leighton’s career as a self-supporting artist, writer and wood engraver.

When Four Hedges came out, only those readers in left wing literary and artistic circles would have known that Noel, the leading man in Transplanting Walnut Tree, was Henry Noel Brailsford, one of the most influential Socialist journalists of the early twentieth century. Brailsford was also Leighton’s ‘Companion within the Four Hedges’, as she describes him in the book’s dedication. Born in 1873, Brailsford had been married in 1898, the year of Leighton’s birth, to his student at the University of Glasgow, the Scottish suffragette activist Jane Esdon Mallocha. The pair made each other miserable and quickly separated, but Mallocha refused to grant Brailsford a divorce. When Mollacha died in 1937, Brailsford fell apart. Instead of marrying Leighton, he left her. She was devastated and turned to America, where for the next fifty years she pursued with renewed passion and devotion her everyday art of ordinary people.

The English Leighton of Four Hedges is just as bold, just as inventive, and just as radical as the American Leighton; no matter her subject matter, the gendered politics of a woman’s hand and body are pressed into the image on a printed page just as surely as they are engraved into the block of wood. In defiance of all lingering Victorian codes of feminine propriety, the St. John’s Wood born and bred Leighton wrote and illustrated Four Hedges and her other countryside books of the 1930s while living with the married Brailsford. Like her literally life-sustaining practice of wood engraving, this was a bodily and spiritual experience, a woman’s radical assertion of her right to independent thought, action and sexual choice. The book is a brave, beautiful, scandalously public love letter from Leighton to Brailsford, testifying to the possibilities of equality in work and art in an English garden composed of black and white in an age of Depression and darkness.

Leighton supplemented her earnings from publishers’ commissions for wood engravings with fees from lecturing and teaching. In 1949 she told an American audience that It is not the person who escapes from the fulness of life. . . who writes or paints best. It is he who lives and who mixes with his ordinary fellows. For it is he who knows life. But never forget that it is work, and yet again, work and work and work. (qtd. in James Hamilton, Wood Engraving and the Woodcut in Britain, p. 99). The words ‘work and yet again, work and work and work’ bring us back to England and to ideas popularized by Leighton’s Gollancz books of the mid-1930s: that rural art is not escape but engagement with the world; that the best artists are those who mix with ‘ordinary fellows’ – the workers of everyday life; and that art itself is labour.