Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

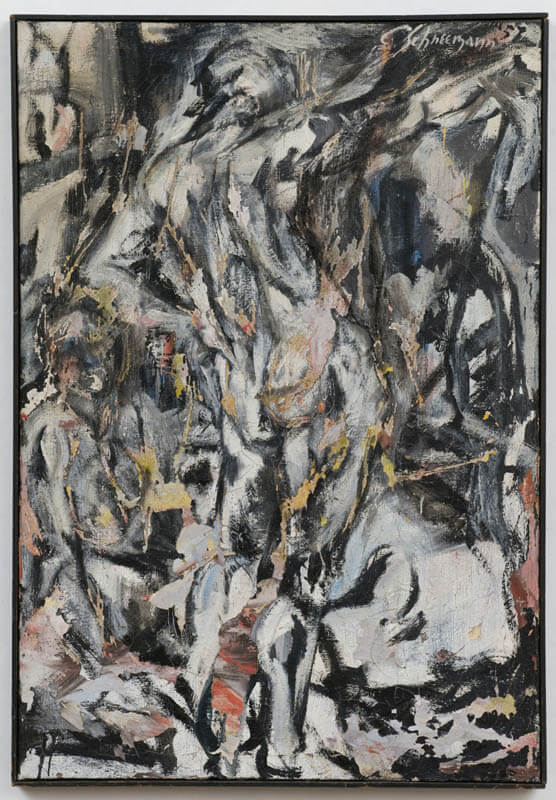

Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) worked relentlessly throughout her career as an artist to defy classification. Formally trained in painting at Bard College (BA) and the University of Illinois (MFA), her oeuvre of kinetic painting, multimedia installations, text, film, assemblage, kinetic theater and performance is imbued with an insistence on her identity as a painter. In her early paintings, she established her style outside the male-dominated formalities of Abstract Expressionism, resulting in unremitting rejection from what she called the “Art Stud Club.”

As her work expanded beyond the canvas, she encapsulated her experience of the personal as political, engaging and disturbing the social order of sexual expression, domesticity, the oppression and objectification of women, human-animal relationships, and the violence of Western military intervention.2 The struggle for recognition and understanding of Schneemann’s work continues beyond her passing in 2019. The major retrospective, Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting, came seven decades into her career, opening in 2016 at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg and traveling to MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main and MoMA PS1 in New York. The first UK-based survey of her work, Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics, is currently on display through early January 2023 at the Barbican Centre.

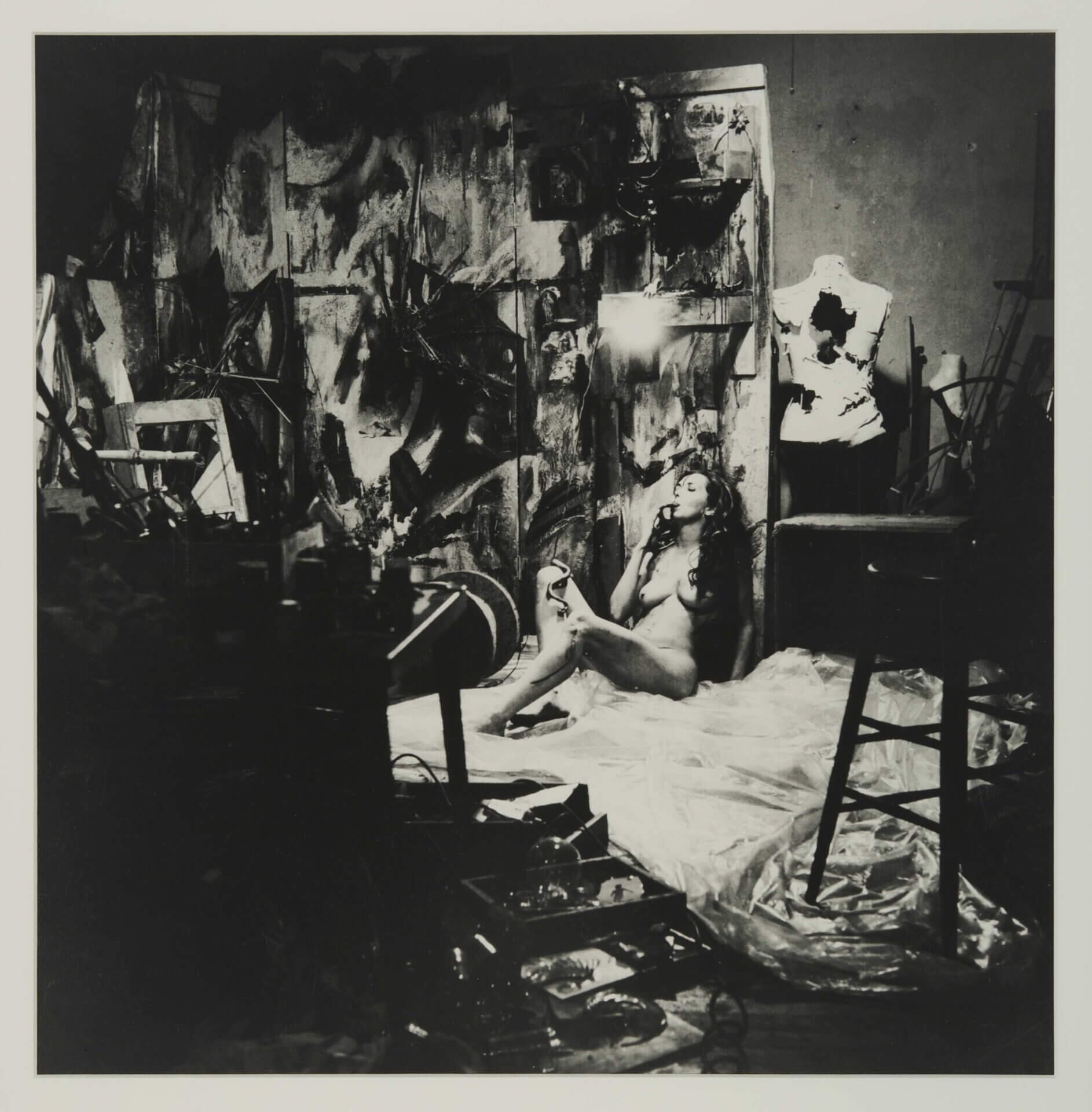

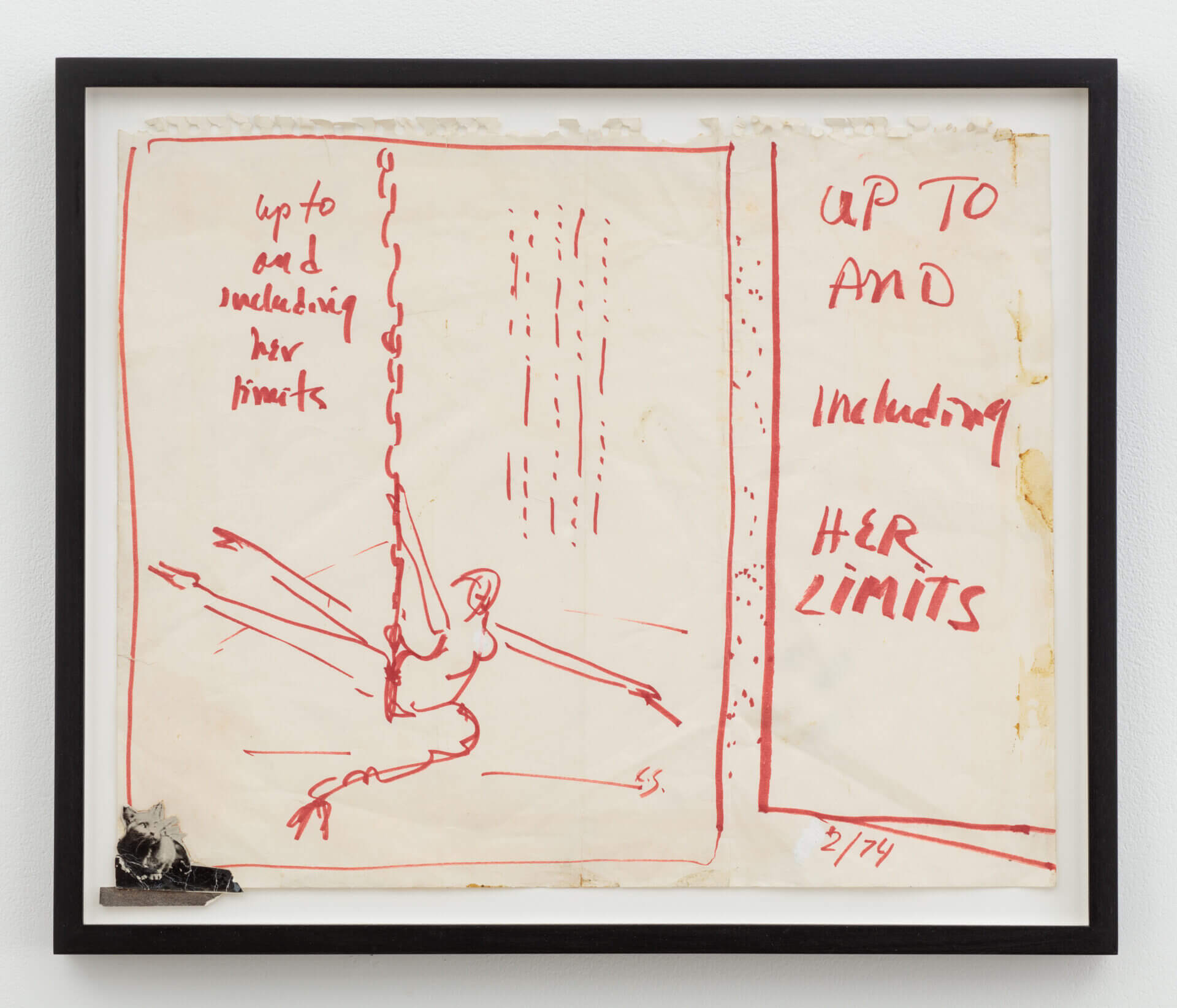

The most readily misunderstood aspects of Schneemann’s work surround her efforts to break with conventions of the naked woman’s body in movement. She rejected the belief that for her body to be viable in performance and constructed in her own image, it had to be stripped of its sexuality and eroticism. She wrote, “Not only am I an image maker, but I explore the image values of flesh as material I choose to work with. The body may remain erotic, sexual, desired, desiring, but it is as well votive: marked, written over in a text of stroke and gesture discovered by my creative female will.” Her radical subversion of the male gaze was powered by the strength of her identity formation, in which she refused to exist in a relationship of causality by men. Schneemann saw the absence of this representation in the art world and acted tirelessly to render its existence. In 1974 she wrote about her work, “In some sense I made a gift of my body to other women: giving our bodies back to ourselves.” Schneemann’s gift challenged social anxieties around flesh: disrupting and complicating oppressive male perceptions of women’s bodies.

As both image and image-maker, Schneemann “[eschewed] the skewed power dynamics that often played out between artist and subject (one that has persistently been understood as male artist female muse), Schneemann considered herself – and by extension, her body – as implicated in all of her work.” Beginning with the series Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera (1963), she claimed her own body as part of her medium, collaging it with the other objects utilized in the photo series: paint, ropes, plastic, mirror shards, a cow skull, garden snakes and other found objects. By integrating herself into her work, she created a complex entanglement between art and artist, challenging the terms by which women artists were granted recognition and admission into the male-occupied territory of Art.

![]()

In Schneemann’s 1991 text, ‘The Obscene Body Politic’, she discusses the culture in which her work existed: “Eye Body (1963), Meat Joy (1964), and my film Fuses (1965) form a trio of works whose shameless eroticism emerged from within a culture that has lost and denied its sensory connections to dream, myth, and the female powers. The very fact that these works remain active in the cultural imagination has to do with latent content that the culture is still eager to suppress.” Fuses, in particular, had volatile reception. As Elena Gorfinkel Describes in Energetics and Erotics: On Schneemann’s Cinema: “A screening at Cannes in 1969 purportedly ended with forty frustrated male audience members ripping up all the seats in the front rows with razor blades. The film’s image of heterosexual coupling and explicit sex was at odds with early 1970s feminist politics and its suspicion of sexual representation, both in the emergent critique of pornography as well as in the rifts between heterosexual feminists and lesbian separatists.” The film is an ode to heteroeroticism, neither pornographic nor medically instructive. Instead, it collages a portrait of bodies in sensual dialogue, relaying Schneemann and her partner James Tenney having sex. The camera is both a third perspective and protagonist, while Schneemann’s feline companion Kitch is situated as a neutral observer of these moments of intimacy. Schneemann’s aesthetic approach was in direct opposition to the conventions of 1960s pornography that used an ogling address, for which female sexuality was an exotic commodity. Through this portrait, Schneemann powerfully challenged the dominant male gaze that had, until that point, defined the representation of sexual experience and cast women as sexual objects. Fuses imagines erotic subjectivity, pleasure, and self-exploration.

In some ways, the quick dismissal of her work by her male contemporaries cut deeper than reactions of flat-out rage. Loyal friend and supporter Robert Haller wrote to Schneemann regarding Fuses in November 1977, “After your screening at the Carnegie Institute four years ago, somebody said to me that the film wasn’t much, it was so obvious, ‘That pussy was Schneemann’s cunt…’ as if that snide cliché summed up the film, then defused it for him. How he missed the point (and how sad). We live in the womb of the universe, which is echoed all around us (in your vagina, your eyes, your camera, my mind, the ocean…) in nature, and in your film.”