Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988) remains an elusive yet potent force within British Surrealism. While her legacy is often overshadowed by her male contemporaries, Between Worlds, the new retrospective at Tate St Ives, seeks to redress this. The show assembles over 170 artworks and archival materials that chart Colquhoun’s evolution from early Surrealist experiments to the deeply esoteric, alchemical works that defined her later years. The exhibition highlights Colquhoun’s work at the unique intersection of Surrealism and the occult. This precarious yet fertile space led to her exclusion from the British Surrealist Group in 1940, as the artist’s steadfast belief in the mystical potential of art clashed with the movement’s political aims. Yet as André Breton wrote in the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), Surrealism must aim for “pure psychic automatism,” a space where “thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, is beyond all aesthetic or moral preoccupation.” Colquhoun’s work embodies this vision, existing at the threshold of dream and waking life, of the rational and the supernatural. This exhibition, then, is not only a restoration but a reconsideration of Colquhoun’s place within this legacy.

Overall, the exhibition benefits from its meticulous chronological structuring, which not only traces Colquhoun’s artistic development but also highlights the broader influences that shaped her career. The progression from academic training to Surrealist engagement and, ultimately, esoteric abstraction mirrors her journey of self-discovery, allowing visitors to experience the full breadth of her explorations in both art and mysticism.

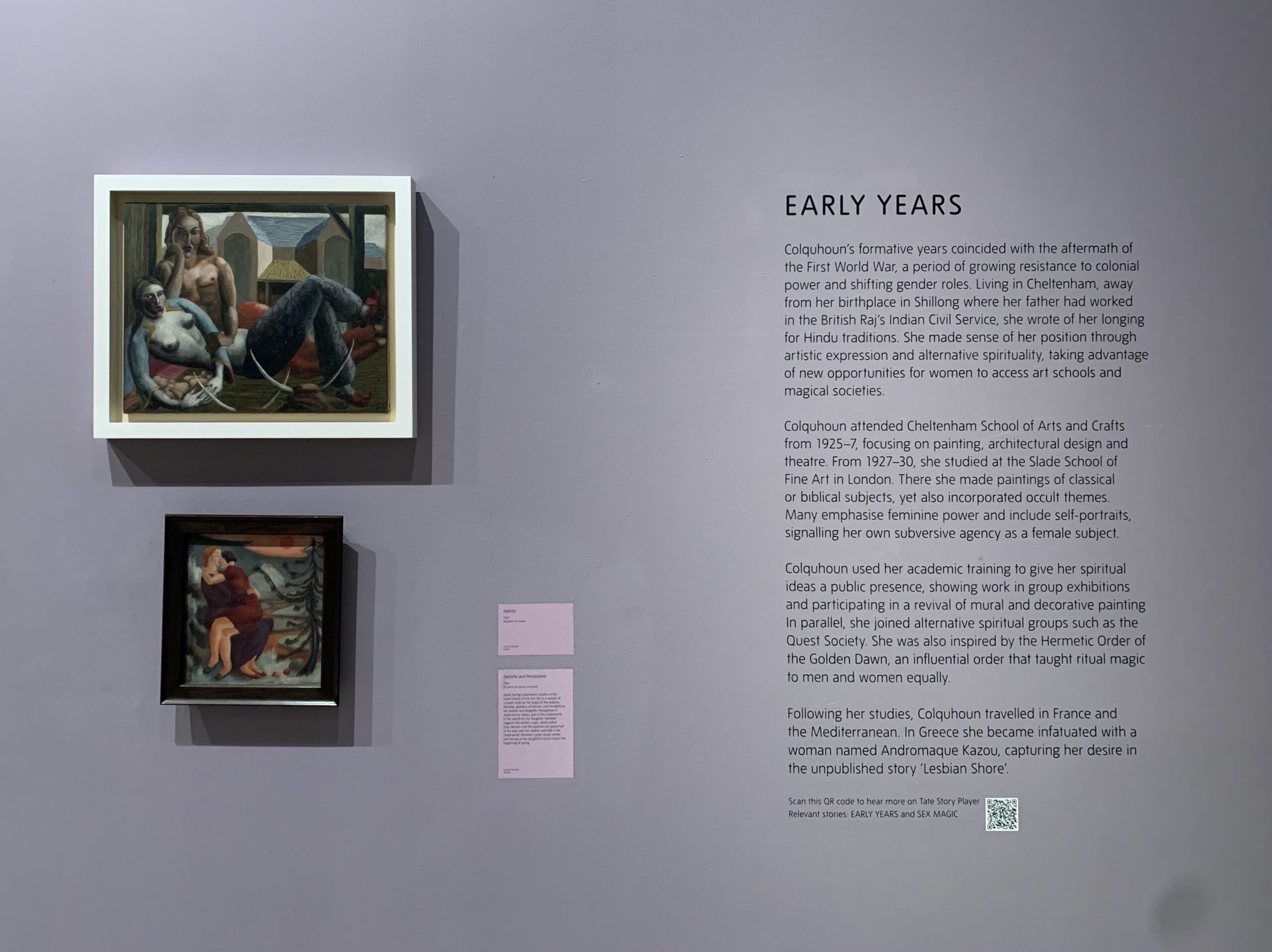

The opening room Early Years, painted in a soft lavender hue, presents Colquhoun’s formative years. Her works from this period, such as Nativity (1929), reflect her early engagement with classical and biblical themes, yet even here, traces of her later subversive tendencies are evident. In contrast to traditional depictions of the Nativity, Colquhoun presents an unidealised, almost austere composition, emphasising maternal power over passive divinity. Surrounding works depict mythological subjects and religious imagery, revealing her absorption of Renaissance traditions while simultaneously pushing against their constraints.

A pivotal shift occurs in the second room, divided into two sections: Into Surrealism and The Mantic Stain. The transition between these is marked by a dark purple wall—a striking curatorial decision that underscores the rupture between Colquhoun’s initial Surrealist engagement and her later esoteric turn.

In Into Surrealism, the influence of Breton’s surrealist principles is evident in works that embrace the concept of the ‘double image’ and dream-based symbolism through architectural, botanical, and bodily motifs. The adjacent section, The Mantic Stain, explores Colquhoun’s experiments with automatism, a technique championed by Breton as a means of accessing the unconscious and the possibility of a multi-dimensional universe. Autumnal Equinox (1949) stands as a commanding example. Derived from an image she perceived in the grain of a painted door, its concentric circles reference chakra energy centers, a motif that aligns with her growing interest in spiritual systems beyond Western traditions; the imposing

female figure at the center commands respect and attention. The interplay of structured forms and fluid automatist technique manifests Colquhoun’s belief in art as a conduit between conscious and unconscious realms.

Colquhoun’s immersion in myth and mysticism becomes the focus of the subsequent rooms. The Magical Workings room, painted in a dusky pink, shifts the focus from mythic landscapes to esoteric diagrams and alchemical studies. Here, Colquhoun’s interests converge in works that visualise sacred geometry, mystical unions, and divine transformation. Diagrams of Love—paired with an accompanying poem—articulates her exploration of sexual and spiritual alchemy, where gender dissolves into an all-encompassing cosmic balance.

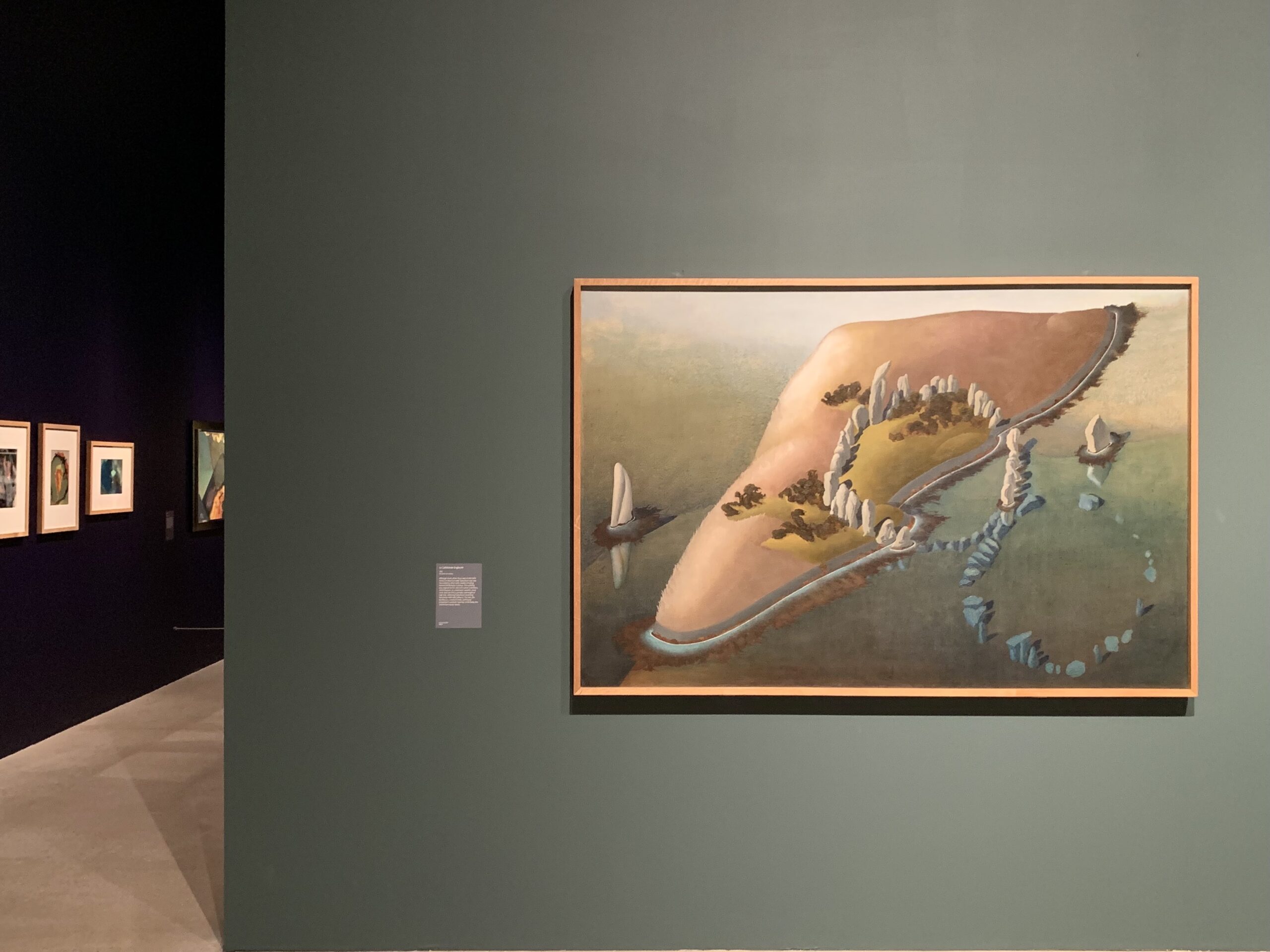

The final rooms, Earth Energies and Later Years, bring the exhibition full circle, emphasising Colquhoun’s deepening engagement with landscape, environmental preservation, and spiritual ecology. The moss-green walls of Earth Energies evoke the Cornish landscapes she came to see as living entities, inscribed with ancient rites and subterranean power. This engagement with the landscape takes on particular significance in the exhibition’s setting at Tate St Ives. Cornwall, where

Colquhoun spent much of her later life, was not simply a backdrop but a vital source of artistic and spiritual inspiration. Her deep attunement to the region’s ancient monuments and ecological rhythms is underscored through her visionary interpretations of Neolithic sites such as the Merry Maidens. La Cathédrale Engloutie (1954) resonates with Colquhoun’s belief in the mystical forces embedded in ancient landscapes. Inspired by the submerged ruins of Er Lannic and the legend of Ys, the work explores dissolution—of stone into water, history into myth. Her treatment of colour is particularly evocative: sedimentary blues and ethereal whites blur boundaries between material and immaterial, solid and spectral. The painting seems to pulsate with unseen forces, echoing Breton’s assertion that Surrealism could unlock hidden dimensions of reality.

The exhibition is notable not just for its paintings but for its inclusion of a diverse range of Colquhoun’s creative output, showcasing her sketches, automatic drawings, and literary works alongside her paintings. Her writings, often overlooked in discussions of her practice, reveal the depth of her intellectual engagement with alchemy, myth, and esotericism. These materials provide crucial insight into the conceptual frameworks underpinning her visual art, demonstrating the symbiotic relationship between her written and painted worlds.

The exhibition excels in presenting Colquhoun’s practice as multidimensional, spanning Surrealist automatism, landscape, portraiture, and esoteric symbolism. The chronological structure serves an essential function in this first major retrospective, ensuring that her artistic and spiritual evolution is clearly articulated. The division of the Into Surrealism and The Mantic Stain sections is particularly effective, reinforcing the rupture in Colquhoun’s relationship with British Surrealism. The later rooms, devoted to magic, ecology, and alchemical transformation, underscore her singular vision and persistent engagement with mystical traditions.

In many ways, Between Worlds is a fitting title for this retrospective. Ithell Colquhoun was always navigating thresholds—between Surrealism and the occult, the seen and the unseen. This exhibition not only restores her position within Surrealist discourse but also gestures toward the vast, largely uncharted depths of her practice. Its presence in Cornwall, a landscape that profoundly shaped her vision, makes this recognition all the more poignant. It is a long-overdue celebration of an artist who defied easy categorisation, forging a path that, decades later, still resists containment.

Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds runs at Tate, St. Ives from 1 February – 5 May 2025.