Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Discussions of Surrealist eroticism have been somewhat clouded by a reductive focus on male artists, and their purported misogyny and objectification of women. However, by looking to the work of women artists, a richer, more complex exploration of eroticism soon emerges. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the work of the Argentine born artist, Leonor Fini.

Born in Buenos Aires, and having spent her early childhood in Trieste, Italy, Leonor Fini arrived in Paris in 1931. Familiar with Freudian theory, Fini’s work reflected the Surrealist’s interest in sex, dream, and desire, and she soon became acquainted with the Surrealist group in Paris. A fiercely independent woman, however – and refusing to submit to the authoritative André Breton – Fini’s associations with the group remained social rather than formal, and she refused the Surrealist label. This attitude of defying categorisation extended to Fini’s personal life too: she had both male and female lovers, shunned societal expectations of marriage, instead living communally with two men.

This experience of a more open, fluid intimacy is present in the erotic dreamworlds Fini paints. Her 1938 painting From One Day to Another depicts a group of partially undressed women lounging intertwined in a shallow pool, set against the backdrop of crumbling villa ruins. Their wet dresses cling tightly to their bodies; the fabric slashed seductively across their buttocks or draped low to reveal bare breasts. Yet whilst the painting recalls the traditional bathhouse scene – an exoticised trope explored through the male gaze throughout art history – Fini subverts this, instead conjuring up a matriarchal space where women reign supreme.

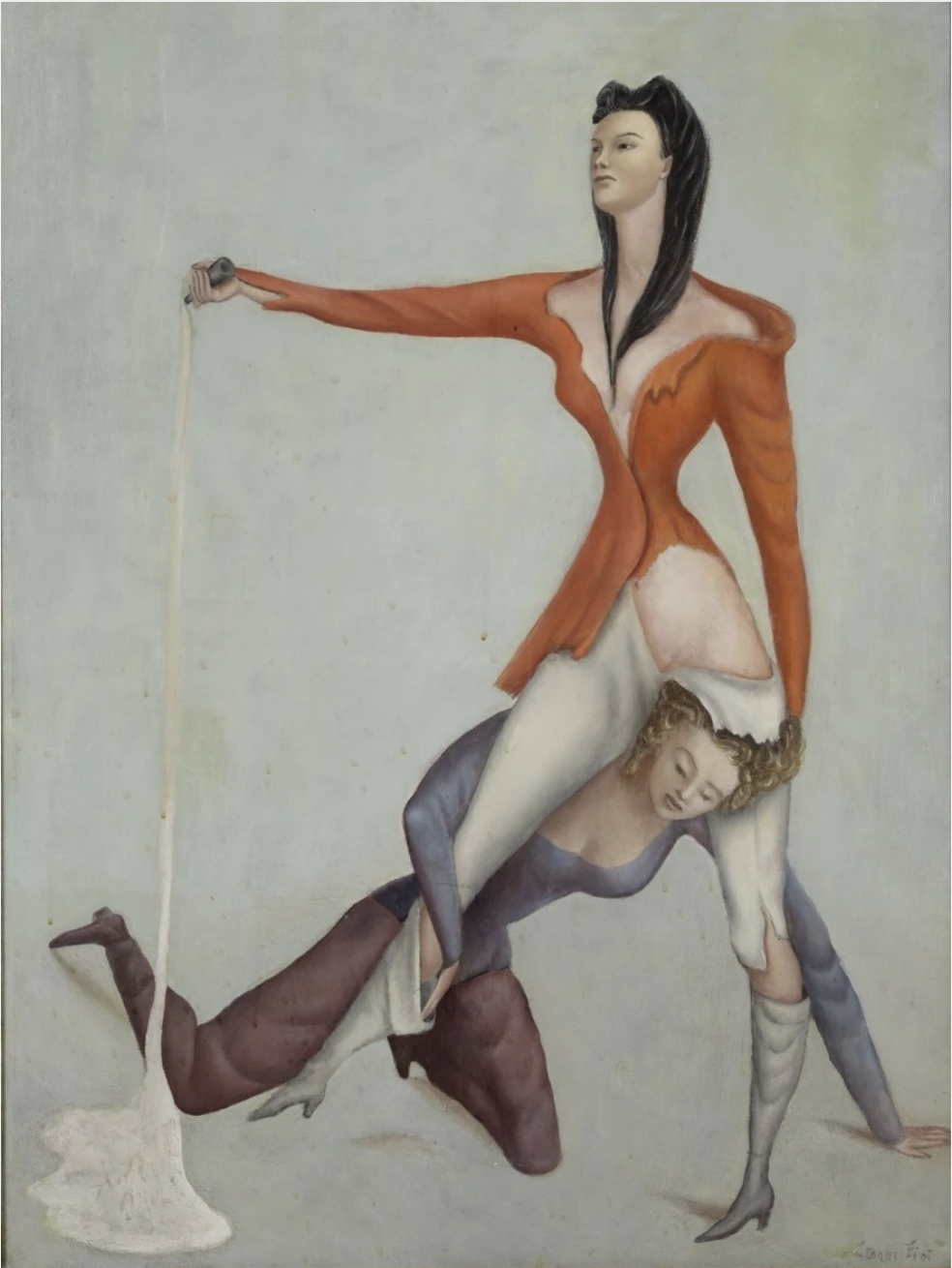

We again see this exploration of erotic intimacy through the female gaze in Fini’s painting L’arme Blanche (The White Weapon) (1936), exhibited at The International Surrealist Exhibition in London the same year. The painting depicts two women. One – with dark hair and arched eyebrows bearing a resemblance to Fini – stands dominantly: legs apart in heeled boots, head tilted upwards and arm outstretched. Her torn clothing peels off, revealing her exaggeratedly hourglass figure. With a defiant gaze, she pours a milky liquid from a small bottle, which pools on the floor. Between her legs, the second woman crawls on all fours, her hand wrapped around the others calf, delving into her boot. The painting is erotically charged -following its exhibition, a Daily Mail critic described Fini’s work as “a couple of slaps on the face of decency that should not be allowed to pass unnoticed” – yet also portrays a peculiarly playful physical closeness, depicting an ambiguous, tactile intimacy between women.

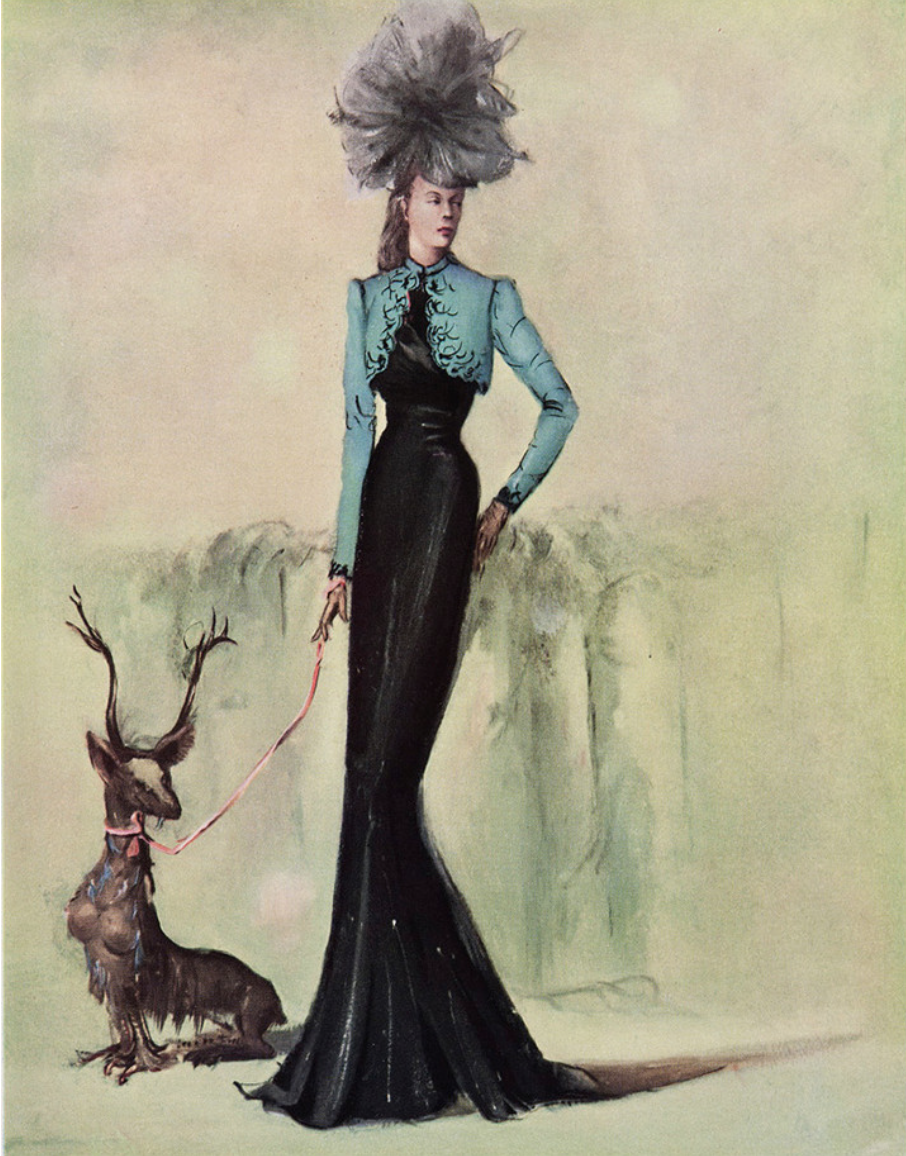

Regularly attending costume parties and masquerade balls in theatrical dress, Fini soon became popular with society and art photographers at the time. Aware of Fini’s reputation as both a young, up-and coming artist and a glamorous muse for leading photographers, the avant-garde designer Elsa Schiaparelli lent Fini dresses to wear at events ‘for the publicity value’. In return, Fini illustrated several of Schiaparelli’s collections for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. In these illustrations, the bodies of couture-dressed women are intertwined with beast-like animals and mythological creatures: a recurrent theme throughout Fini’s oeuvre, which would manifest most frequently in the guise of the Sphinx. Fini was not the only one of Schiaparelli’s collaborators to explore this animalistic eroticism: In 1936, Schiaparelli collaborated with the artist Meret Oppenheim on a fur-covered bangle. The piece of jewellery would supposedly inspire Oppenheim’s 1936 piece Object/Breakfast in Fur; a fur lined teacup simultaneously implying both oral pleasures and revulsion as one imagines the feeling of wet fur between lips.

In 1936, Schiaparelli commissioned Fini to design the bottle for her new perfume, Shocking!, which launched in 1937, its suggestive name reflected in Fini’s scandalous hourglass design, modelled on the voluptuous curves of the bawdy sex goddess and Hollywood bombshell, Mae West. The same year, Schiaparelli’s provocative fashions – including a dress with inflatable breast “falsies” to be blown up with a straw – prompted Vogue to comment that with Schiaparelli, “sex appeal was no longer a matter of subtle suggestion”.

The bottle alludes to the rituals of couture fittings – a process Fini hated, but appreciated the ceremonial nature of – with the tailor’s dummy torso fragmented by a measuring tape. However, in place of a head, the neck erupts into a blooming bouquet of flowers. The floral headed woman was a popular Surrealist motif, appearing in Dalí’s Necrophiliac Springtime (1936) – which Schiaparelli held in her personal art collection, and inspired Sheila Legge’s 1936 costumed performance “Surrealist Phantom of Sex Appeal”, part of the International Surrealist Exhibition. A vision of the Freudian uncanny, the performance saw Legge gowned in white, standing motionless in Trafalgar Square; her head encased in a mask of roses, and carrying an artificial leg. As the title implies, with Legge’s figure-hugging dress and peek-a-boo raised hemline, the performance had an underlying sexual allure.

This sexual allure of the floral headed woman was also present in the scent of Shocking!. A heady mix of warm and spicy patchouli, clove, and amber; atop notes of honey, rose, and jasmine, the perfume created a sensual, exoticised scented fantasy, intermingled with a nostalgia for the powdery floral perfumes of 19th century Paris. However, the addition of animalic civet and musk return the fragrance to the bodily. Conjuring up erotically charged fantasies of hot skin, animal fur and sweat, Shocking was not just sensual, but undeniably sexual, earning its reputation as sex perfume.

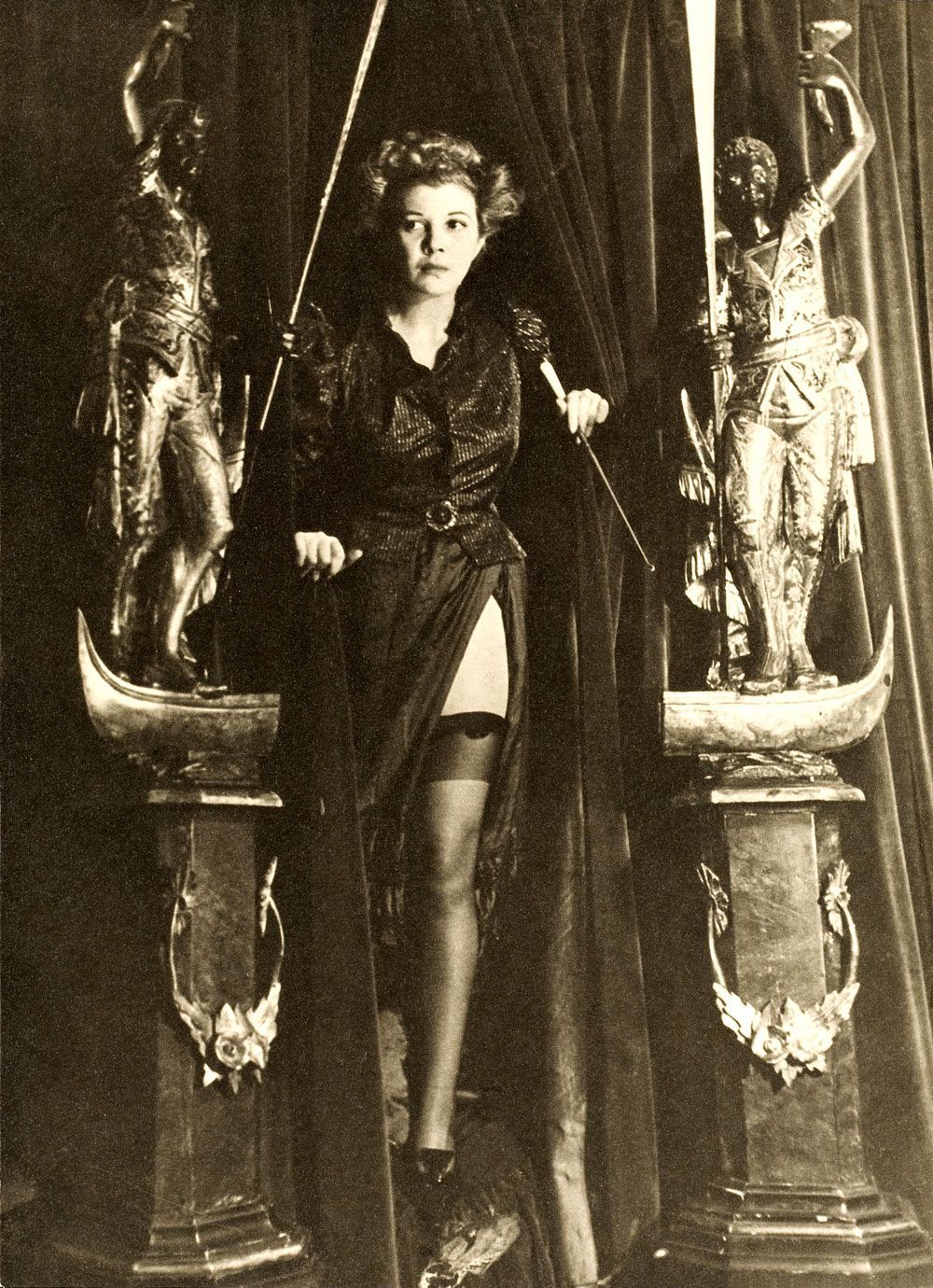

The intoxicating effect that a perfume like Shocking could have on people would not be lost on Fini: In Chris Vermorcken’s 1987 documentary on Fini, Fini’s lover Constantin Jelenski recalls meeting her in a gallery and smelling her perfume before he could see her, the traces of scent leaving an almost physical pillar of presence in the air . Indeed, whether through heady perfumes or decadent costuming, Fini understood the power in constructing an exterior reflection of one’s inner identity through theatrical self-fashioning. In the same documentary, Jelenski comments with admiration on Fini’s ability to use dress to “somehow transform herself..to revitalise herself, and electrify herself, which is totally bewildering.” We see this in photographs taken by her friend Dora Maar, where Fini steps out from behind velvet drapes in a puffed spangled blouse, and floor length skirt, split to her hip to reveal thigh-high stockings.

In her love of theatrical dressing, we can appreciate the close intertwining of Fini’s life and art. Photographs of Fini attending a masquerade party in a feathered owl mask inspired the costumes of Pauline Reage’s 1954 sadomasochistic erotic novel Story of O, which in turn Fini later illustrated herself. Fini’s artistic exploration of erotic torture, sadism and bondage demonstrates how the influence of the libertine philosopher Marquis de Sade was clearly imprinted into Fini’s visual language.

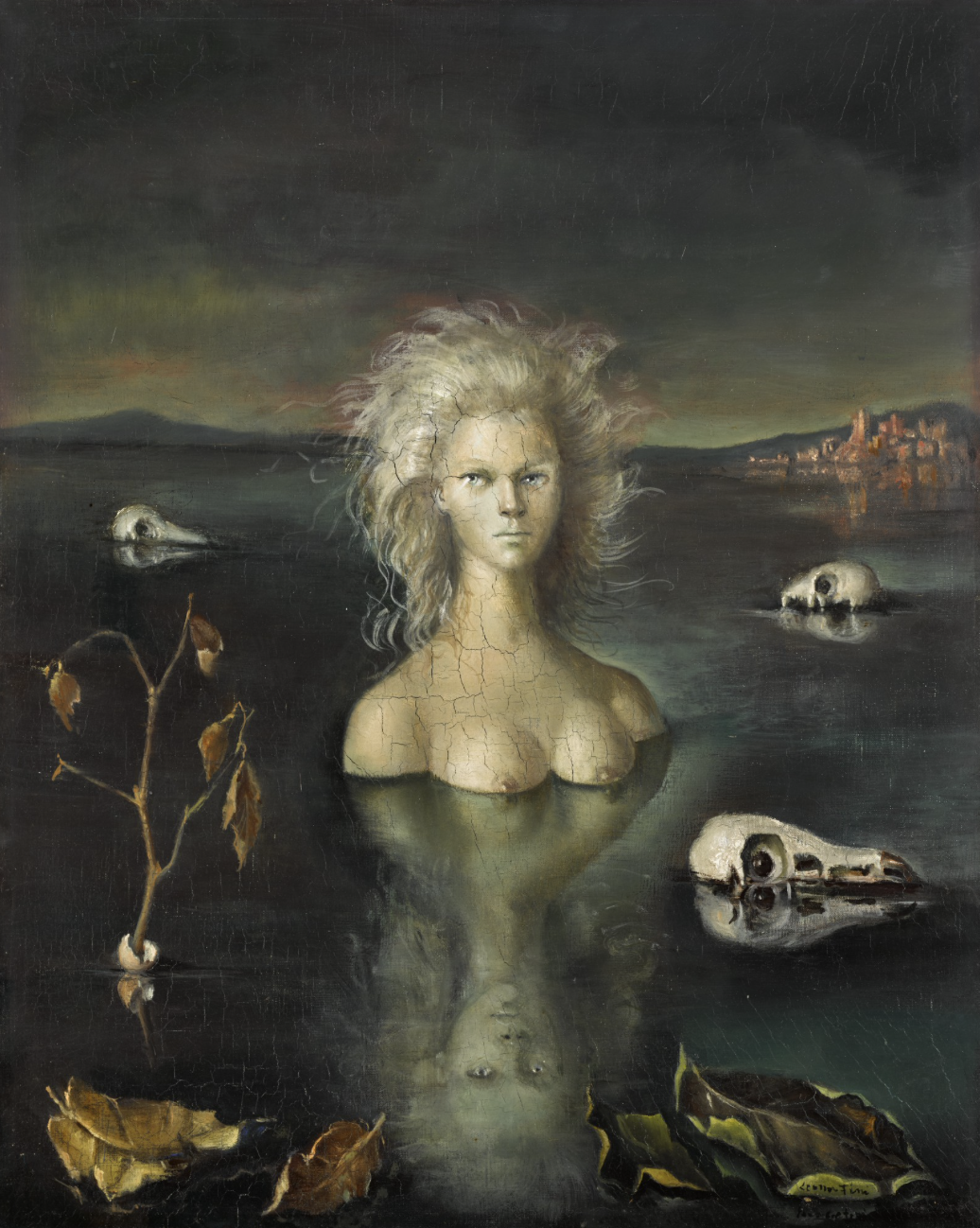

It’s in such works that we clearly see how Finis’s exploration of erotic fantasy was not bound by romantic sentimentality, but instead ventured into much darker areas of the psyche. We see this exploration of the macabre in Fini’s 1949 painting Le Bout du Monde (The End of the World). Here, under an apocalyptic night sky, a nude woman is partly submerged in an inky pool of water, her breasts bob above the water, as animal skulls and decaying leaves gather around her, her wide-eyed reflection in the water hinting at a darker underworld. Fini captures the fragility of decay – a skill perhaps honed when she learnt to draw cadavers in morgues and tenderly explores the fine line between life and death: a humanistic reminder of the finite nature of our own lives.

By embracing eroticism in all of its complexity, Fini’s entire oeuvre – and indeed, life – serves as a reminder to not settle for the banal, but to utilise our erotic imagination to transcend our everyday reality. Her dreamworlds invite us to delve deep into our own desires and revel in our fantasies; encouraging us to free ourselves from social conventions; to think beyond boundaries and borders, and to revolt against a life merely assigned to us. In daring us to entertain the impossible, Fini’s work demonstrates the radical power of the erotic to make our whole lives more expansive.