Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Although her importance was long downplayed, German artist Hannah Höch (1889–1978) was a major figure in the history of avant-garde art, and one of the few women to actively take part in Dada activities. Sometimes described as less virulent in her sociopolitical critique of the Weimar Republic than fellow Dadaists Raoul Haussmann, John Heartfield, or George Grosz, Höch’s stance ultimately exceeded the ephemerality of Dada. The movement was linked to historical events while Höch turned her attention to issues relating to the status of women. This topic was a driving force of her work, whether in her collages, paintings, or objects, and was particularly embodied by her recurrent use of the doll as a motif, which she turned into a grotesque allegory of the female object.

The doll, and by extension the mannequin or puppet, was a key image of the Dada movement, which Höch was introduced to by Raoul Haussmann, whom she met in 1915. In the uncertain and fractured times of the first half of the twentieth century, these humanoid objects could act as a distorting mirror to confront a modern and bourgeois society. At the First International Dada Fair of 1920, a huge carnivalesque, iconoclastic show and a founding exhibition for the movement, John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter’s well-known pig-headed Prussian soldier, the Preussischer Erzengel [Prussian Archangel] hung from the ceiling. Standing there was also John Heartfield and George Grosz’s mannequin-slash-cyborg Der wildgewordene Spiesser Heartfield [Philistine Heartfield Gone Wild], also a work used to castigate with violent sarcasm the social order of the Weimar Republic. Despite Heartfield and Grosz’s reluctance to allow a woman at the event, Höch presented several works at the Fair. She was the only woman at the event. In addition to her collages, she showed two dolls, known as her Dada-Puppen. The following year at a Dada ball, she herself wore the doll’s costume. One photograph shows her posing as a twin of her creation. The abstract, burlesque femininity of these dolls was intended to embody the stereotypes of femininity and the passive role to which women were relegated in the first half of the 20th century.

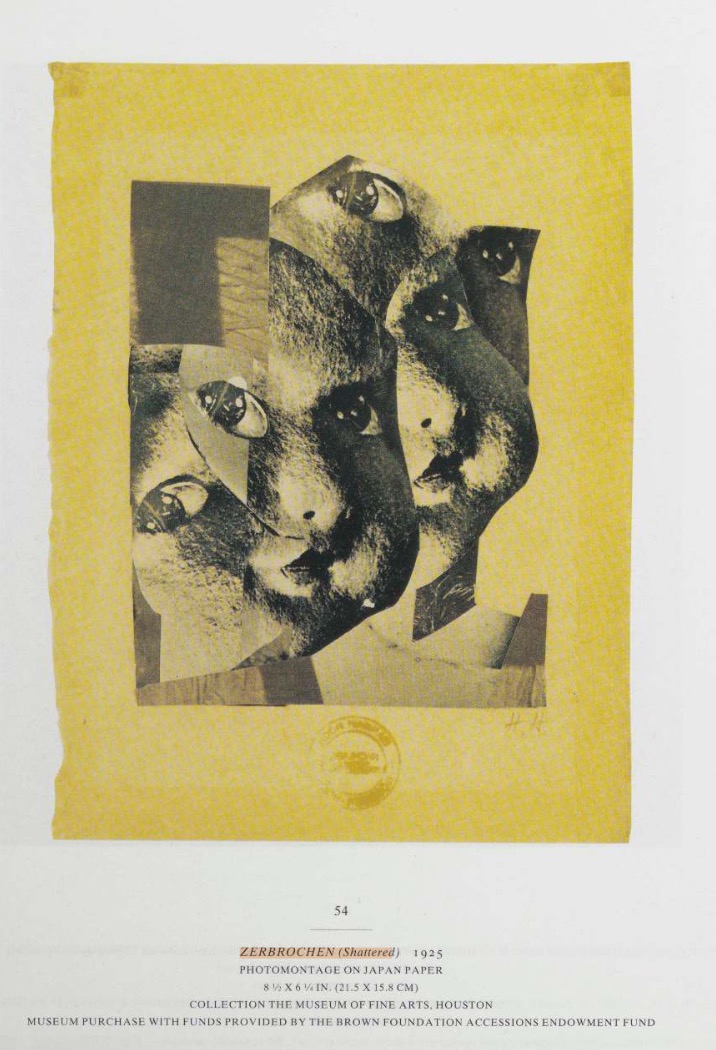

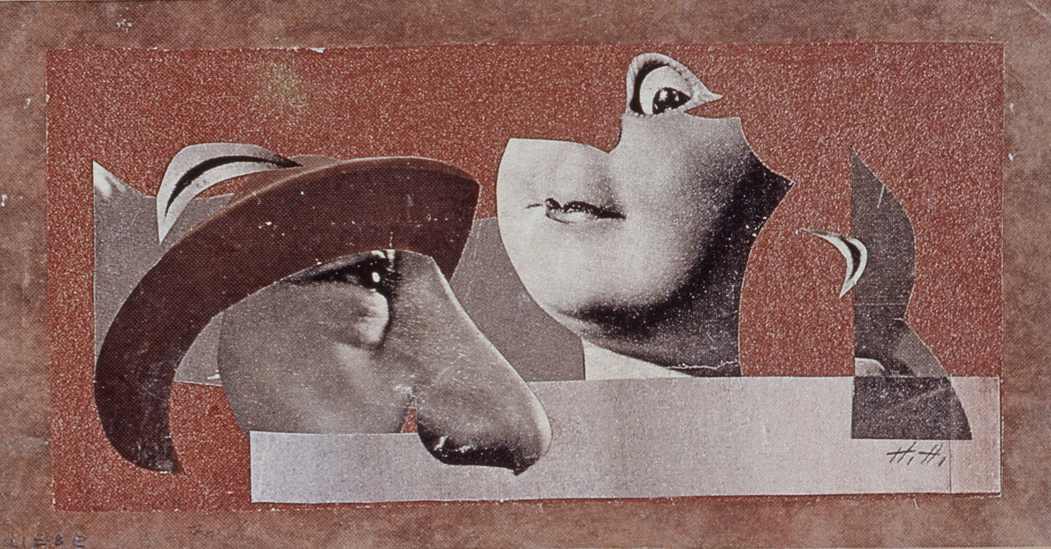

Post-war Germany saw the emergence of the Neue Frau or New Woman. This androgynous, emancipated female figure symbolised modernity and liberation for women, who had just obtained the right to vote. In reality, the figure was an ambiguous one. While « new women » had to respond to new ambitions and expectations, they were still subject to traditional patriarchal vision. Höch ironically highlighted the contradictory facets of this myth. Despite their short hair, her dolls, with their slim waists and pronounced breasts and nipples, address both the idea of the nurturing woman instilled in girls from a young age through their toys as well as the unreachable bodily ideals promoted by the mass media and advertising. The very use of the doll motif is a sarcastic nod to women’s place in society. This toy is subject to the will of its creator, just as women are subject to the stereotypical expectations. Rendered as dolls, women are dehumanised, at the mercy of a patriarchal society. In her collages Zerbrochen [Shattered] (1925) and Der Meister [The Master] (1926), in which she used the image of one of the most popular dolls of the Weimar period, she dismantled this deeply connoted object, distorting its purity and innocence into grotesqueness.

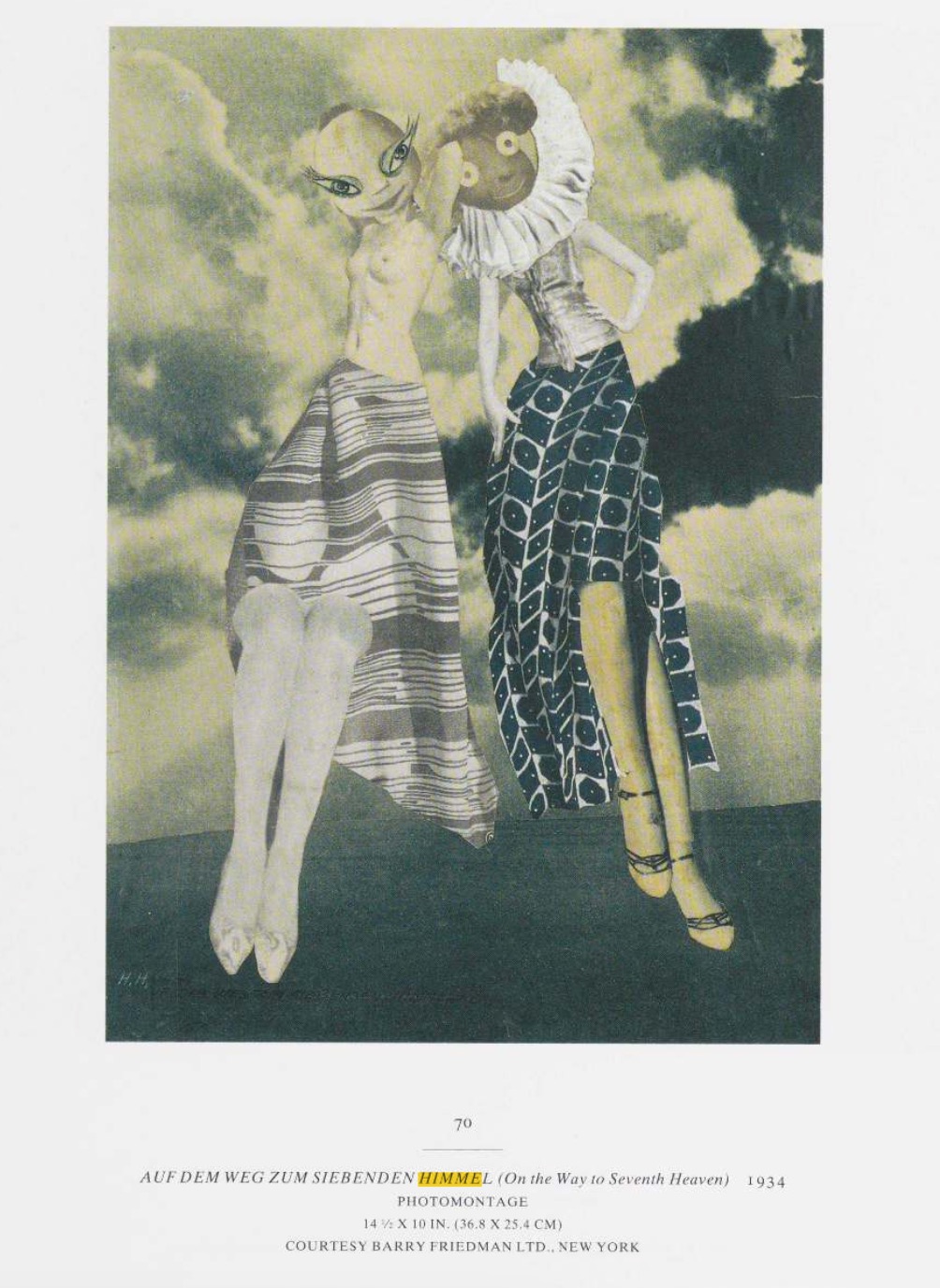

Höch uses the same doll in her collage Liebe [Love] (1926), which mocks the marriage between a man and a woman. Despite their emancipation, “new women” were still expected to reach this conventional union. This collage can be seen all the more sarcastic considered that Höch lived for ten years with the writer Mathilda (Til) Brugman, whom she met in Amsterdam in 1926. In her collage Auf dem Weg zum Siebenden Himmel [On the Way to Seventh Heaven] (1934), she used an image of her Dada-Puppen to portray a same-sex couple, a motif increasingly present in her work at the time.

In addition to romantic relationships, Hannah Höch played with gender norms, which experienced a certain fluidity in the Weimar years. We can draw a parallel between the practice of collage and the relationship that each of us might have with a doll. In the same way that its owner transforms this little character as they please, changing its clothes and hairstyle or even dismembering it to put its head on another body, Höch’s collages dismantle bodies to go beyond the limits of identity, gender, or race. She does so in her well-known Aus einem ethnographischen Museum [From an Ethnographic Museum] collage series (1924–34), in which the new women’s bodily features are combined with the body parts of non-Western sculptures. These collages can be seen as a critique of both traditional Western beauty standards and the racist vision of exotic beauty that was prevalent at the time. A pioneering critique that is still very resonant today.

With the use of dolls, Höch also reclaims them as objects long associated with women. Höch worked for some time as a pattern designer for several magazines belonging to the Ullstein press group. This period strongly influenced her work, including her dolls. Höch’s vision of applied arts went beyond the simplistic view that they were a women’s hobby. In 1917–18, she wrote in a applied arts magazine: “but you, craftswomen, modern women, who feel that your spirit is in your work, who are determined to lay claim to your rights (economic and moral), who believe your feet are firmly planted in reality, at least y-o-u should know that your embroidery work is a documentation of your own era! ». Höch saw art as a reflection of generational concerns, and the applied arts were always a part of it. For Dr Ralf Burmeister, Head of the Artists’ Archives at the Berlinische Galerie which holds the Höch archives, such a stance is « a proto-feminist statement.»

Whether as an object or as part of a collage, the doll was a means for Hannah Höch to address issues of identity politics. Her vision and her works have influenced many artists, both directly and indirectly. The way Cindy Sherman used the image of the doll in the 1990s to denounce fashion stereotypes is a case in point. And although a whole world separates from Hannah Höch’s Dada-Puppen to Greta Gerwig’s feminist Barbie, there’s no denying that the doll remains a powerful tool for deconstruction.