Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

This article explores the intricate connection between art and domesticity, examining a range of artworks spanning from the second wave of feminism to those created by contemporary artists. The second wave of feminism marked a pivotal juncture that laid the foundations for contemporary practices that continue to explore and reinterpret domestic life in their work.

Throughout history, the notion of women’s place within the domestic sphere has been a defining aspect of societal expectations. Rooted in the “cult of domesticity” and the “cult of true womanhood,” these ideals imposed upon women during the late 19th century encapsulated prescribed roles that predominantly encompassed white upper-class women. This concept, introduced by Barbara Welter in 1966, created a rigid framework that relegated women to a confined space of domestic responsibilities. However, this narrative was far from universal, as Black women and working women remained marginalized, excluded from these prescribed norms while still grappling with the confines of domesticity.

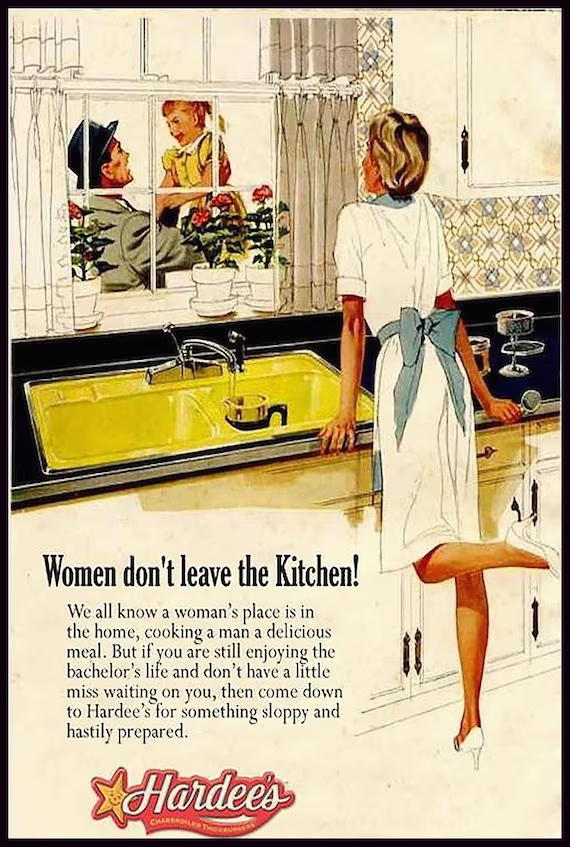

Virginia Woolf’s assertion in 1929 that “Women have sat indoors all these millions of years so that by this time the very walls are permeated by their creative force” underscores the creative potential constrained by domesticity. While her essay primarily addresses women’s role in writing, it has relevance for artists exploring the intricate dynamics of women within domestic spaces. The aftermath of World War II brought forth an era of consolidated gender roles and stereotypes, vividly portrayed through prevalent advertisements, particularly from the 1950s and 1960s. These advertisements reinforced traditional gender norms, confining women to the role of housewives, devoid of individuality and ensnared within a domestic prison.

However, The second-wave feminism movement of the 1960s and 1970s sought to address various gender inequalities and issues, including those related to domestic life and women’s roles within the household. The term “Homesickness” from Imogen Racz in her book, ‘Art and the Home: Comfort, Alienation and the Everyday’ refers to a desire to escape home because it makes women sick of being homebound and lonely. A good example of this concept is found in Birgit Jürgenssen’s artwork I Want Out of Here!, 1976, where she positioned herself against a glass surface on which the title was inscribed. This portrayal depicted the notion of home as a place of confinement. Alexandra Kokoli, a gender studies specialist describes home “as a site of crisis and violence” for women; “a place of work and responsibilities that are endlessly repeating and inescapable”.

Women artists and feminists have been drawn to themes that directly relate to their own experiences: the female body within the space it’s confined to, namely, the home. This subject is explored from both perspectives – as a comforting space and as a place of confinement. It’s important to note that these “feminine” themes have often been disparaged by the academic establishment, which tends to regard them as lacking in significance or importance.

Women artists, like Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, embraced domesticity as a subject matter to confront issues of gender inequality, reproductive rights, and the marginalization of women’s creative contributions. Their iconic 1972 exhibition, “Womanhouse” holds a significant place within Western feminist art. It delves into the theme of domesticity through several of the artworks showcased within it:

Waiting, 1971 by Faith Wilding shows the psychological experience of domestic labor carried out by women. It condenses women’s lives into a lengthy, repetitive, monotonous monologue lasting about fifteen minutes. Seated on a rocking chair, the artist initiates each sentence with “waiting,” highlighting the significance of waiting in women’s lives. Women often remain passive while awaiting the opportunity to allocate time for themselves, fulfilling the expected life stages imposed upon them. This serves as an illustration of a life that lacks fulfillment, allure, and vitality – one that’s passive and unattractive. This ceaseless waiting becomes a representation of the tragic banality that women’s lives often find challenging to transcend.

Within the theme of women and the domestic sphere, some artists have shown particular interest in portraying the female body integrated into the household environment. This integration gradually blurs the boundaries, almost transforming the body into a piece of furniture or a decorative object. For instance, in her series Housewives’ Kitchen Apron, 1975, Birgit Jurgensen wears a stove as an apron which resembles an extension of itself.

Similarly, in Francesca Woodman’s work, specifically Space 2, Providence, Rhode Island”, 1975/76, she captures herself within her studio surroundings, seamlessly merging with the wallpaper and fireplace. This fusion with the interior space blurs and distorts her body, causing it to lose its distinct individuality.

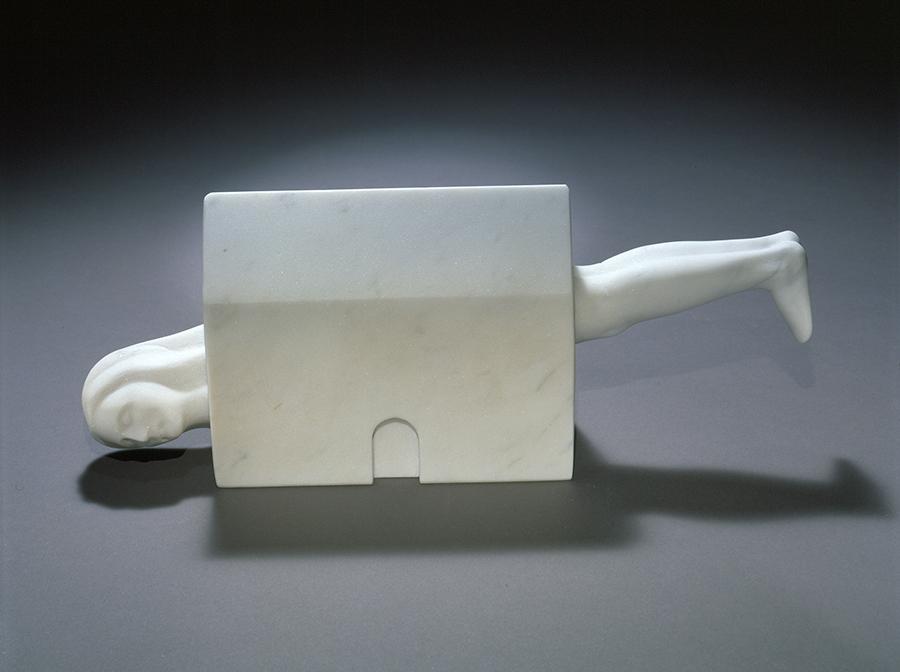

Some artists have gone even further in depicting the fusion of women with domestic space, giving rise to the concept of the “woman-house”:

Louise Bourgeois began in the 1940s her series of drawings and then sculptures called Femme-maisons (Women-Houses). The amalgamation of the female body and the house highlights the connection between woman and house, along with its repressive effects. The female body seems to be trapped within the house. The woman’s body is both exposed and constrained by the architecture. When placing these works in the context of their conception, Bourgeois is torn between the New York artistic life and her domestic work that leaves little room for her artistry resulting in a forced domesticity. The house is both a refuge from the outside world and a cage from which it is difficult to escape.

Niki de Saint-Phalle, throughout her entire career and body of work, aimed to create a space, whether conceptual or tangible, where women can seize power, inhabit a “house” that welcomes their body and spirit with kindness, and transmit their story without distortion. The transformation of a stifled and silent homemaker into a Nana-maison, 1966, both triumphant and welcoming. The Nana is a woman elevated in the public space like a banner, simultaneously sculpture and architecture: her sometimes open body can accommodate others.

In the present day, artists persistently challenge the concept of domesticity. This enduring exploration by artists reflects their ongoing quest to unravel the complexities that lie within the realm of home and personal space. Through their artistic endeavors, these visionaries dismantle preconceived notions, encouraging us to reimagine domesticity’s role in our lives and its broader implications on society.

A prime example is from Palestinian-British artist Mona Hatoum.The artwork Home, 1999 consists of a long industrial table covered with metal kitchen appliances. Wires interlace through the arrangement, attaching to each utensil using crocodile clips. These wires intermittently carry electric currents, illuminating small bulbs beneath items.The sculpture stands behind a barrier of horizontal steel wires, safeguarding viewers from the potentially hazardous current. Mona Hatoum repurposes kitchen objects, traditionally associated with domesticity, into unsettling and menacing elements. The title of the work is ironically tied to the concept of a safe and nurturing home environment. Hatoum challenges this notion, sharing, “I called it Home, because I see it as a work that shatters notions of the wholesomeness of the home environment…” The artist introduces disruptions, both physical and psychological, to counter conventional expectations of home and femininity. “Home” conjures feelings of domestic monotony and the confines of gender roles.

In the same way other artists questions the expectation that still exist today for women to be responsible of the domestic chores. In Tonia Di Risio’s artwork Good Housekeeping, 2001 we can see miniature photographic cutouts of Di Risio, her grandmother and mother. In the artwork Di Risio is doing domestic chores following strict directions by her mother and grandmother. This raises questions about domesticity, which is still passed down from mother to daughter in a kind of integrated sexism and gender expectation.

For Agnes Eperjesi in her artwork A sentence in housework, 2002-2007 each little square represents a daily chore that is imposed on women like justice sentence.

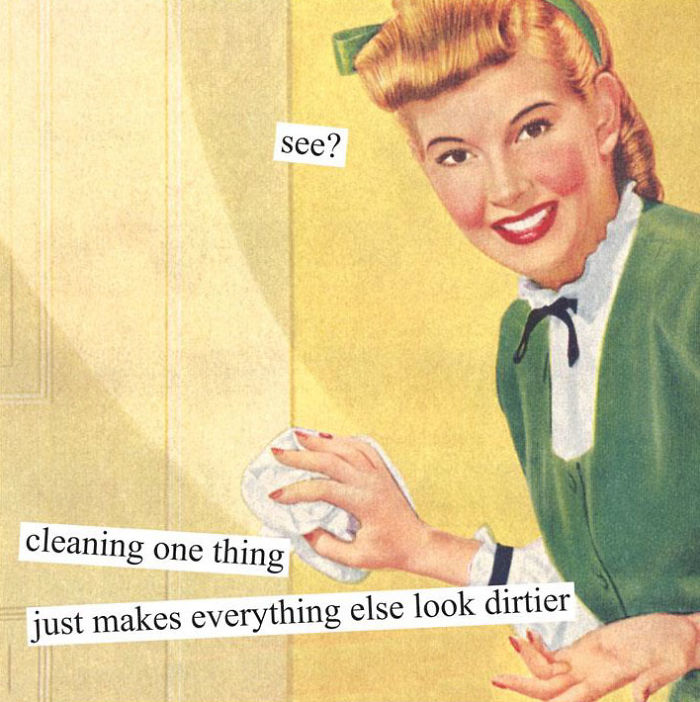

Other artists have opted to use the stereotypical imagery from the 1950s and 1960s into their work while adding a contemporary twist.

Anne Taintor in Trapped housewife, 2000s explores the realm of domestic stereotypes. In her work she uses mid-century advertisements and paired them with ironic captions. It is a critical commentary on the stereotypes of women popularized in the 1940s and 1950s.

In Modern Chess Set, 2005 by Rachel Whiteread the artwork makes a game out of traditional gender roles. It’s a chess set with replicas of vintage dollhouse furniture. Miniature versions of everyday utilities and appliances such as sinks, cookers, ironing boards, buckets, washbasins and dustbins are set against miniature versions of furniture and leisure objects such as armchairs, electric heaters and televisions. These chosen objects show the domestic environment as a place of work for women and leisure for men.

Artists also create impactful works that facilitate the understanding of issues related to domesticity. Infant’s Door, 2015 by Linder is a photomontage featuring a woman with a washing machine as her body. This composition bears a resemblance to Birgit Jurgensen’s artwork “Housewives’ Kitchen Apron” from 1975.

Finally Monica Bonvicini, Pleasant, 2021, is a series of mirrors painted with sentences and quotes by female writers, like Amelia Rosselli, Lydia Davis, Diana Williams and Natalia Diaz, These mirrors converge on the theme of unease arising from relationships and the experience of residing within the confines of domestic spaces.

In summary, this article has delved into the intricate interplay between art and domesticity across recent history. It traced the evolution of women’s roles, from the constraints of the “cult of domesticity” to the liberating impact of second-wave feminism. Artists like Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, Mona Hatoum, and Rachel Whiteread shattered conventional domestic boundaries, challenging norms and revealing the dual nature of domestic spaces. Their works highlighted how the connection between art and domesticity remained a potent force in reshaping societal norms, reflecting the evolving identities of women within their homes.