Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

The hugely ambitious survey exhibition, which celebrates the women artists of mid-20th century gestural abstraction, aims to challenge any misconceptions about Abstract art in the 20th century being a primarily white and male movement. Showcasing 150 paintings over five well-curated sections, this show’s focus begins with the radical turn that Abstract art took in the 1940s giving way to a new movement, termed in the USA “abstract expressionism”. The key figures of the movement are represented and include already established artists such as Lee Krasner (1908-1984), Mary Abbott (1921-2019) and Helen Frakenthaler (1928-2011) as well as lesser-known names such as Asthma Fayoumi (b.1943) and Maliheh Afnan (1935-2016).

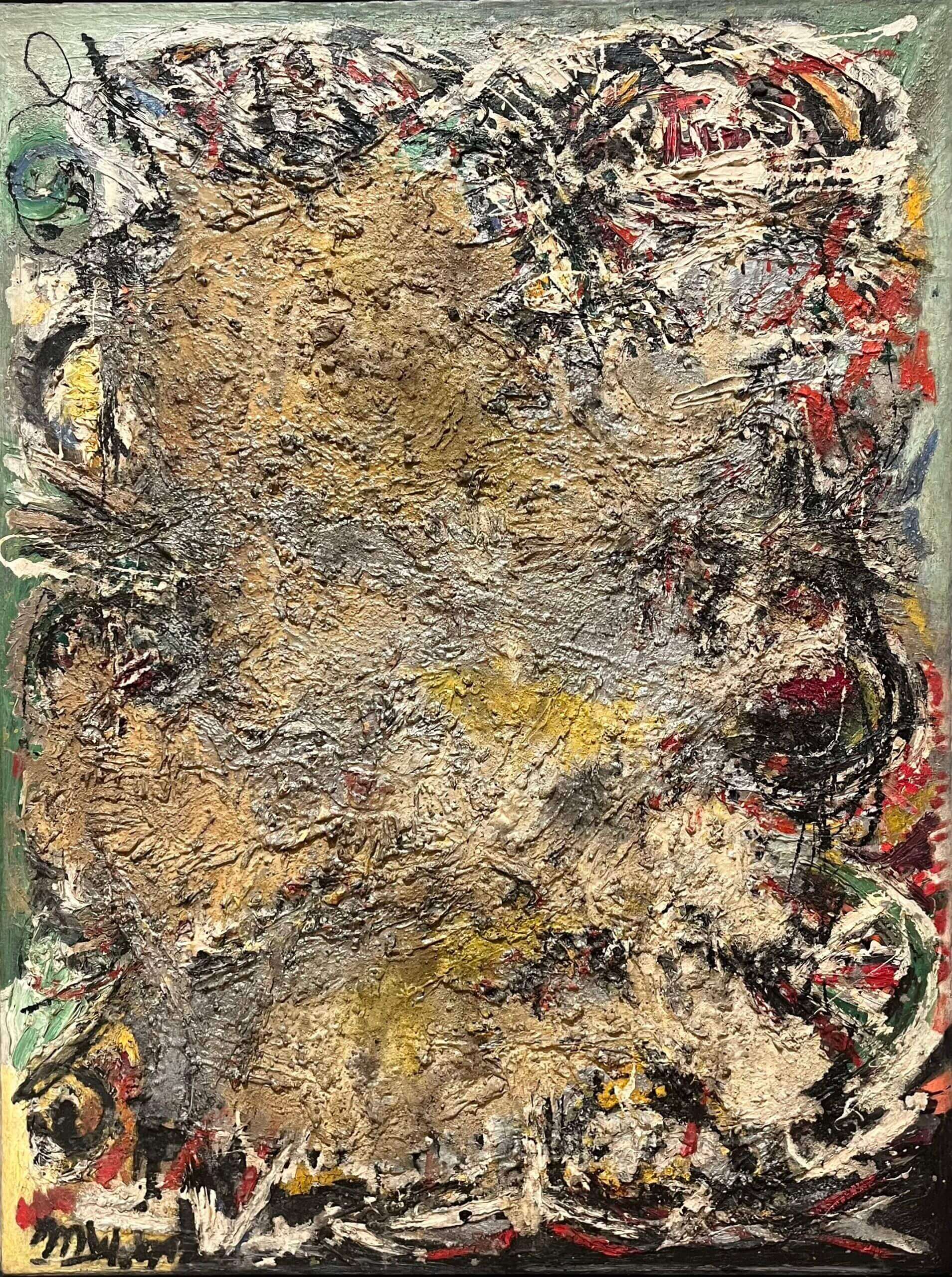

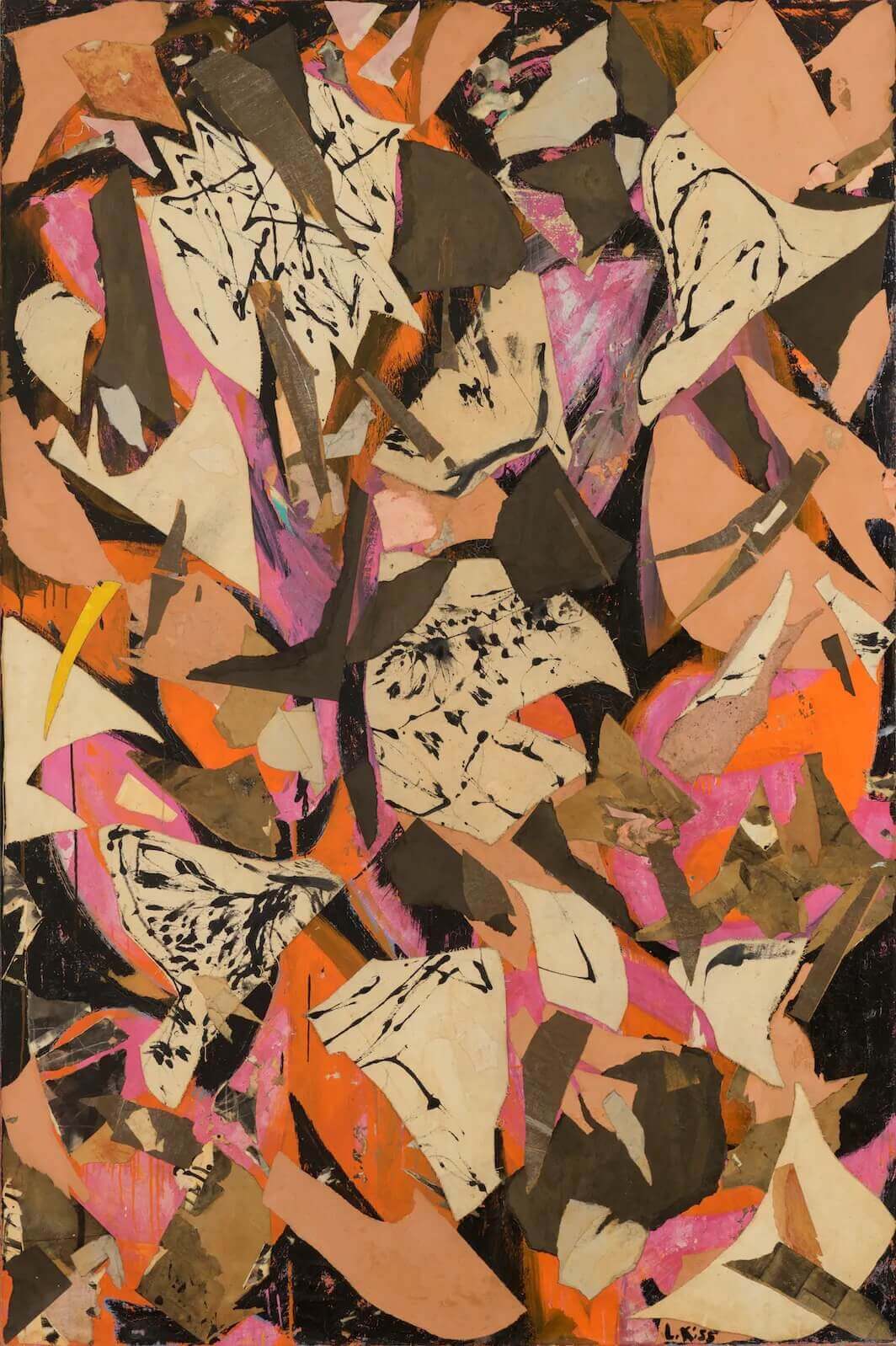

The first section, Material, Process, Time looks at paint as material and process first. Unlike the 19th and early 20th century where Impressionism and Realism dominated the artistic scene, Abstract art offered a far more dynamic and liberating approach where artists enjoyed not being bound by the same constraints as their predecessors. This section shows the many processes of creation and a variety of methods that defined Abstract Expressionism from dribbling, slashing and layering paint whilst materials extended to mud, rags, sawdust, resin, paint tubes, and even cigarette ash. For the first time, the canvas was considered a highly mutable surface: “shaped by violent acts, or tender, intimate gestures, revealing the processes of their making alongside chance, accident at the passing of time”. Defining figures of the first generation of abstract expressionist artists Lee Krasner (1908-1984) and Helen Frakenthaler (1928-2011) are showcased next to lesser-known figures such as Argentinian conceptual artist Marta Minujiìn (b.1943) and Romanian painter and designer Yolanda Mohalyi (1909-1978) giving a fair representation of abstraction’s global effect.

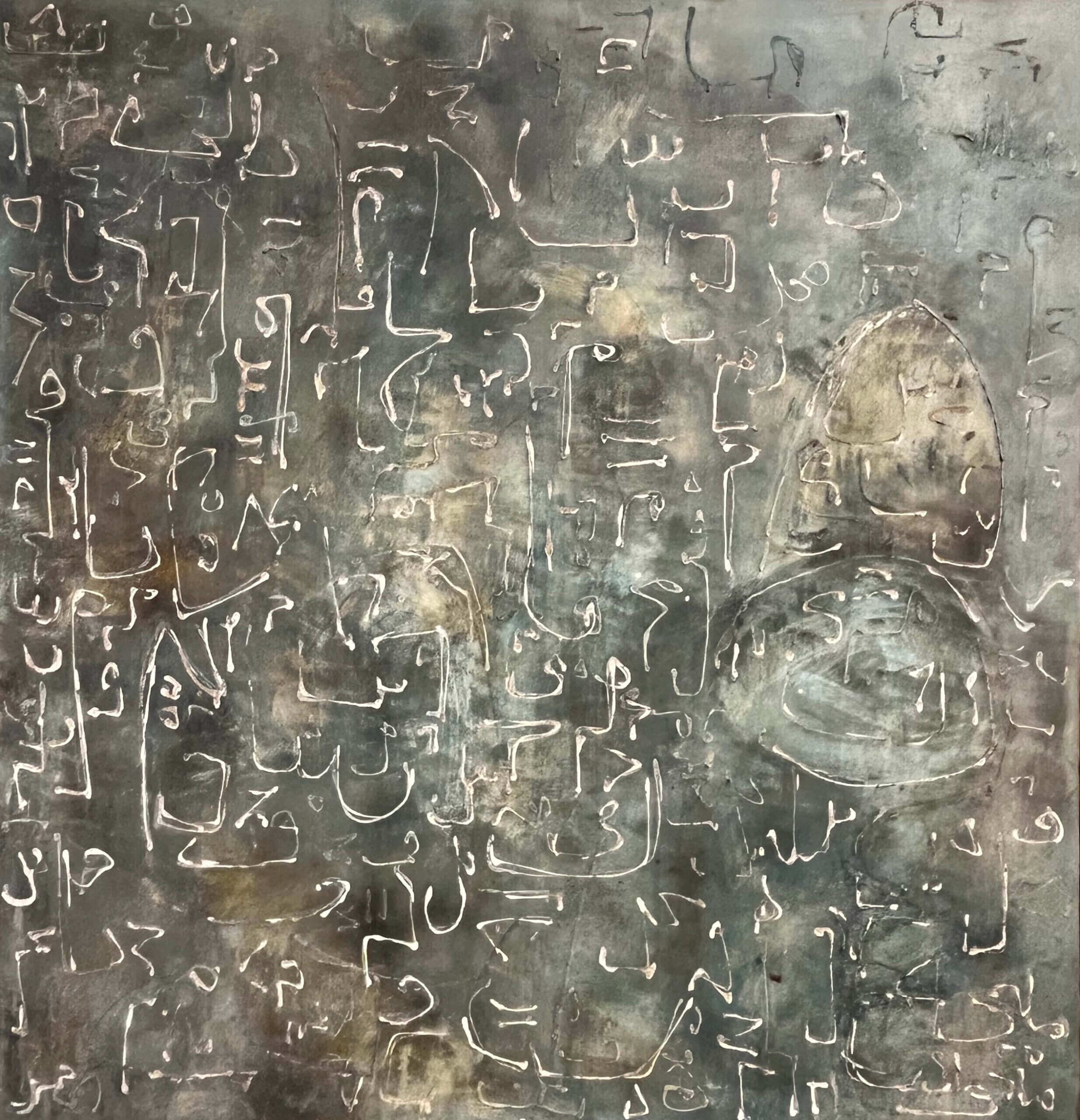

The second section Myth, Symbol, Ritual focuses on symbolic languages drawn from myth and rituals as a recurrent theme in Abstract Expressionism. A practitioner of the movement who is particularly under-represented is Palestinian artist Maliheh Afnan (1935-2016) who formed part of the movement emerging in the Middle East in the new cultural climate of the 1960s. She transforms Arabic and Persian scripts into abstract forms, creating a visual calligraphic language representing memory, loss, nostalgia and displacement evocative of her exile from Palestine in 1948. Many of the works in this section take inspiration from surrealist imagery which historically favoured mythical, allegorical and magical narratives: “The origins lie in the legacies of European and Latin American movements, such as surrealism, Taschisme and Informalism. Spontaneous or ‘automatic writing’ was seen as a way of bypassing rationalism to access unconscious, drives and desires. The artists were also interested, in non-Western systems of belief and their expression through calligraphy and graffiti, as well as in the symbols and cliffs associated with ancient myths and rituals”.

In the third section, Being, Expression, Empathy the curators focus the lens on ‘expression of the self’ which unsurprisingly became the catalyst behind the propagation of the whole movement. Works are featured here in the context of the political and social unrest of the 20th century, most notably the Second World War, global industrialisation, the rise of Civil Rights and postcolonial movements, as well as a Cold War marked by the threat of nuclear extinction between capitalist democracies and communist states. At the same time in Europe, existentialism and nihilism emerged as newly dominant themes in philosophy with thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) and Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) – and those same sentiments echo back into the paintings completed during this time. Against this backdrop, the USA promoted abstract art as a form of western propaganda, to counter the influence of communism: “We can see the manifestation of trauma, feelings of emptiness, or brooding anxiety about a future defended with nuclear weapons through a dark pallet, chaotic, fragmentation, and congested, overwhelming compositions. To break with the past and generate new creativity, artists also embrace destruction in art with the dissolution of form and physical attacks on the canvas. These artists are investigating the very nature of existence. Triggering nonlinguistic, empathetic responses in the viewer.”

In the fourth section: Performance, Gesture, Rhythm, the process of creation through initiating physical movements, such as throwing, jabbing, jumping and dancing as means of marking the canvas is shown in response to the rise in popularity and practice of performance art: “Many of the artists here were influenced by modern dance, and its rejection of traditional forms of ballet for the embrace of physical freedom, in particular for women. There is an acceleration of pure abandonment as painting becomes performance, and the body and the canvas become one in the synthesis of physical and psychic energy.”

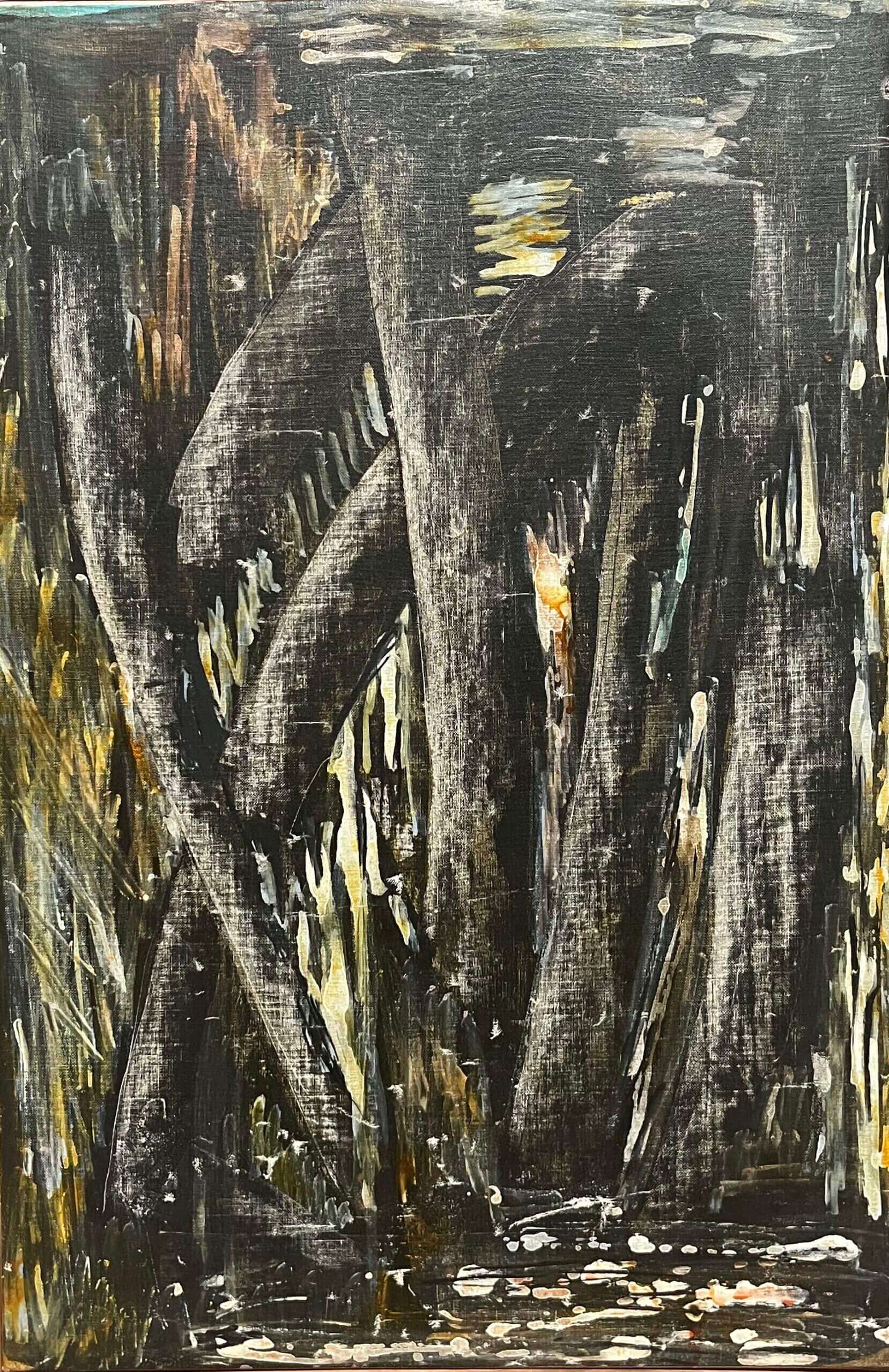

In the last section, Environment, Nature, Perception, the canvas is considered as an environment: “lived experiences of the environment are expressed here through canvases, that emphasise space, texture, light and atmosphere. These artists are still a momentary impression, observed, or remembered, using a pallet drawn from their surroundings, rural and urban. Like poets writing. At this time, they developed an aesthetic language that communicates the instantaneous experience of a time and place, immersing us in the sensations of a landscape or interior. The epic scale of some of these canvases also presents the painting itself as an environment”.

A new wonderful discovery is Behjay Sadr – a pioneering figure in the visual arts in Iran – working later in Rome where she discovered Informalism and more crucially Abstract Expressionism. As we can see with these paintings above, the artist carefully developed her style through rhythmic brush strokes in all-over compositions of curvilinear forms based on nature. Sadr stands amongst numerous women who have received too little acclaim for their contributions to 20th-century Abstraction and continue to remain pivotal in our understanding of a phenomenon, that for over 30 years, shattered all artistic preconceptions, ideals and desires that continues to have a long-lasting impact today.

Confined to a single room at the end of the show, an accompanying exhibition entitled: Feminism, the Body and Abstraction is dedicated entirely to the work of pioneering feminist performance artists such as Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019), Martha Graham (1894-1991), Rosemary Castoro (1939-2015) and Ana Mendieta (1948-1985). What all these artists had in common was using their bodies to explore freedom of expression, sexual agency, oppression and gender politics highlighting how abstraction and performance art from the 1960s onwards informed each other as international movements.

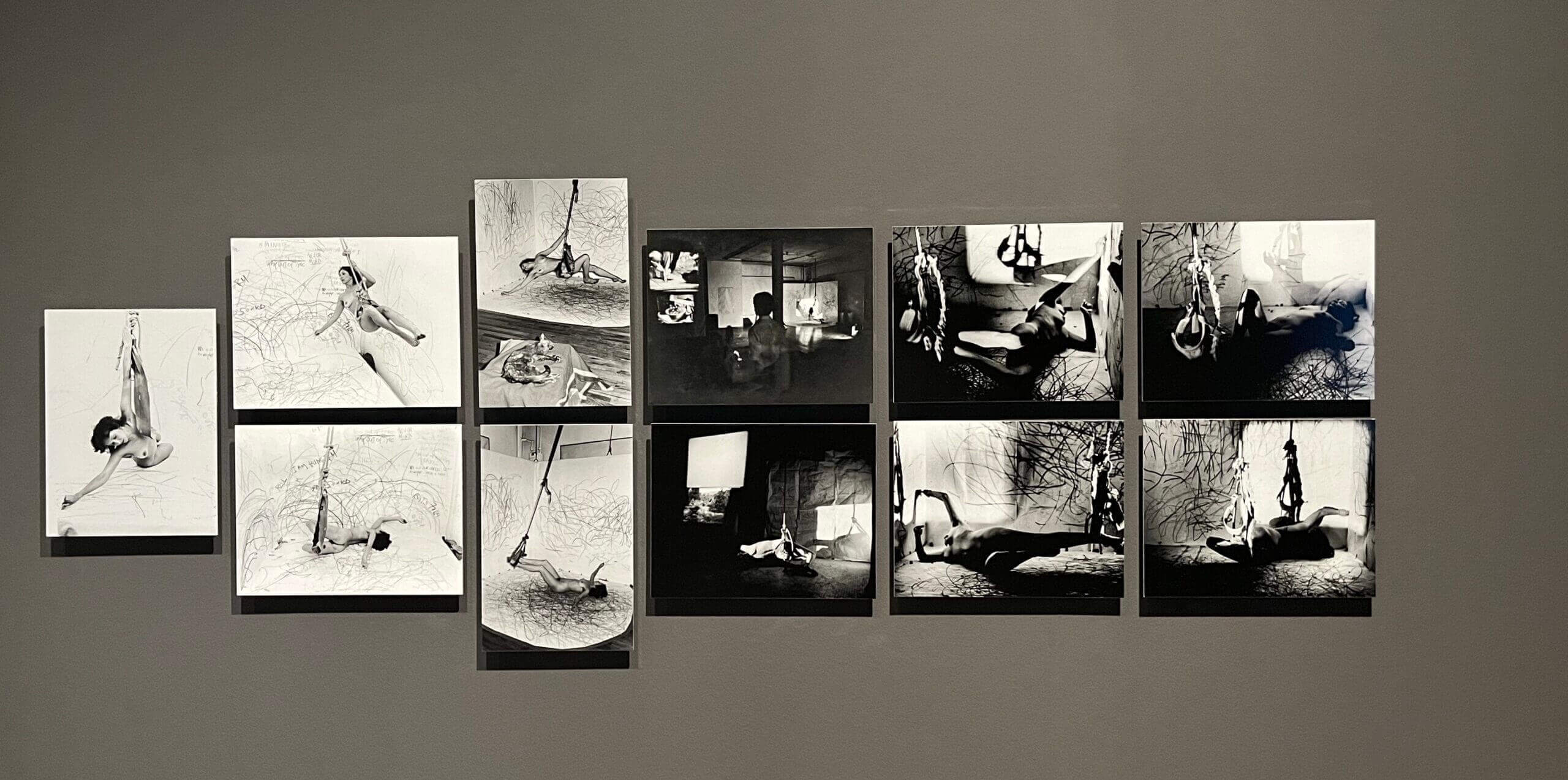

In New York, Carolee Schneemann’s early paintings in the 1950s were influenced by Abstract Expressionism before she began to explore the act of painting using her body as both a tool and ground such as Rosemary Castoro did. In performances, photographs and films, Schneemann explores violence against women and the physical and spiritual connections between her body and the Earth as can be seen in this series of 11 black and white photographs from her performances taken by Henrik Gard, Allan Tannenbaum, Antuony McCall, Gwen Thomas and Shelley Farkas Davis.

In Europe, feminist performances by Renate Bertelmann (b.1943) examine male oppression and sexual violence in a highly symbolic way. Using her body to explore sexuality, gender and eroticism, wearing a breast shirt and latex pacifiers on her fingertips, Bertelmann performed a sequence of meditative actions in which the movement of her hands (expressing joy, pain, fear, aggression amongst other emotions) resulted in the tearing of the ribbons.

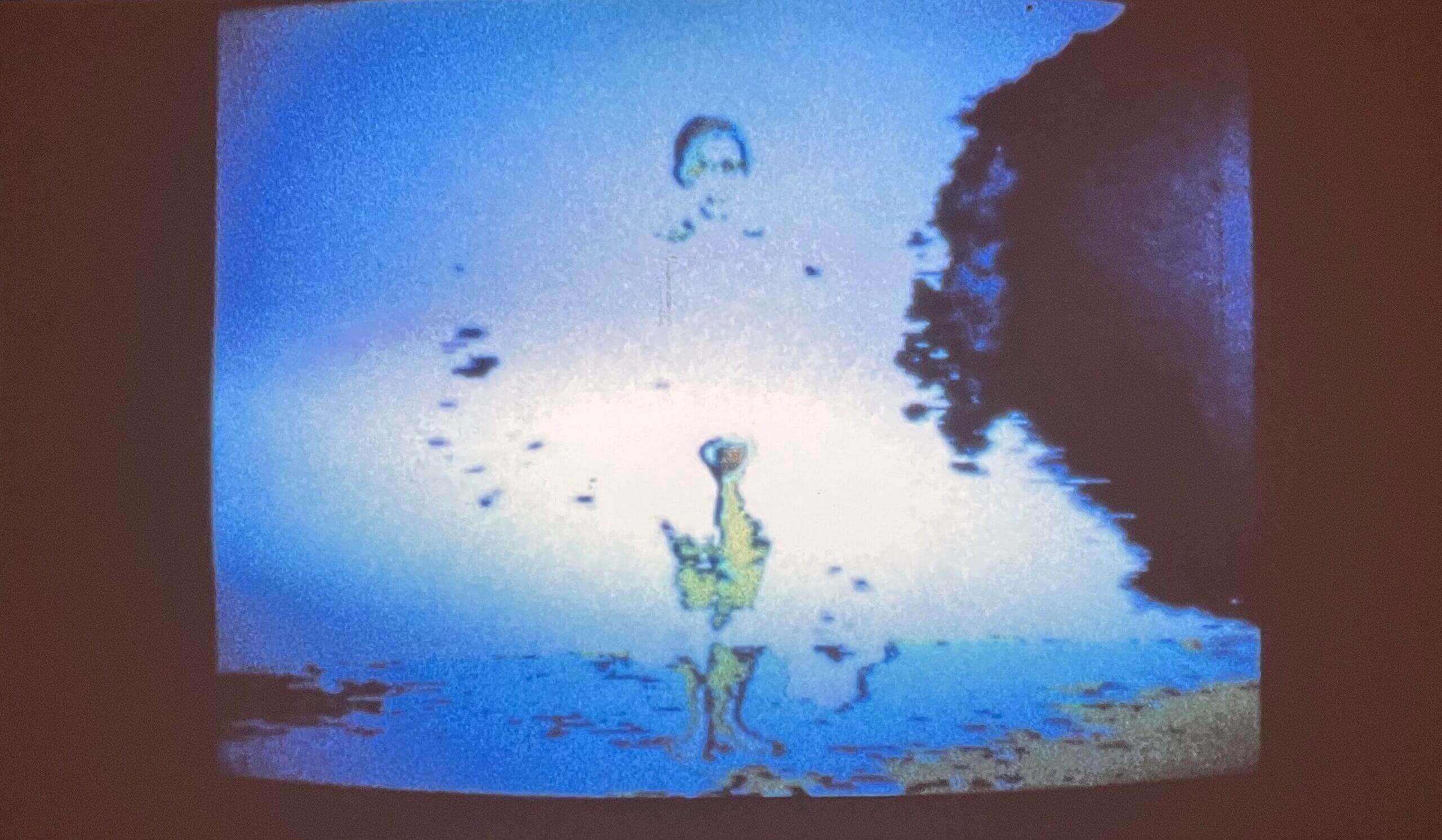

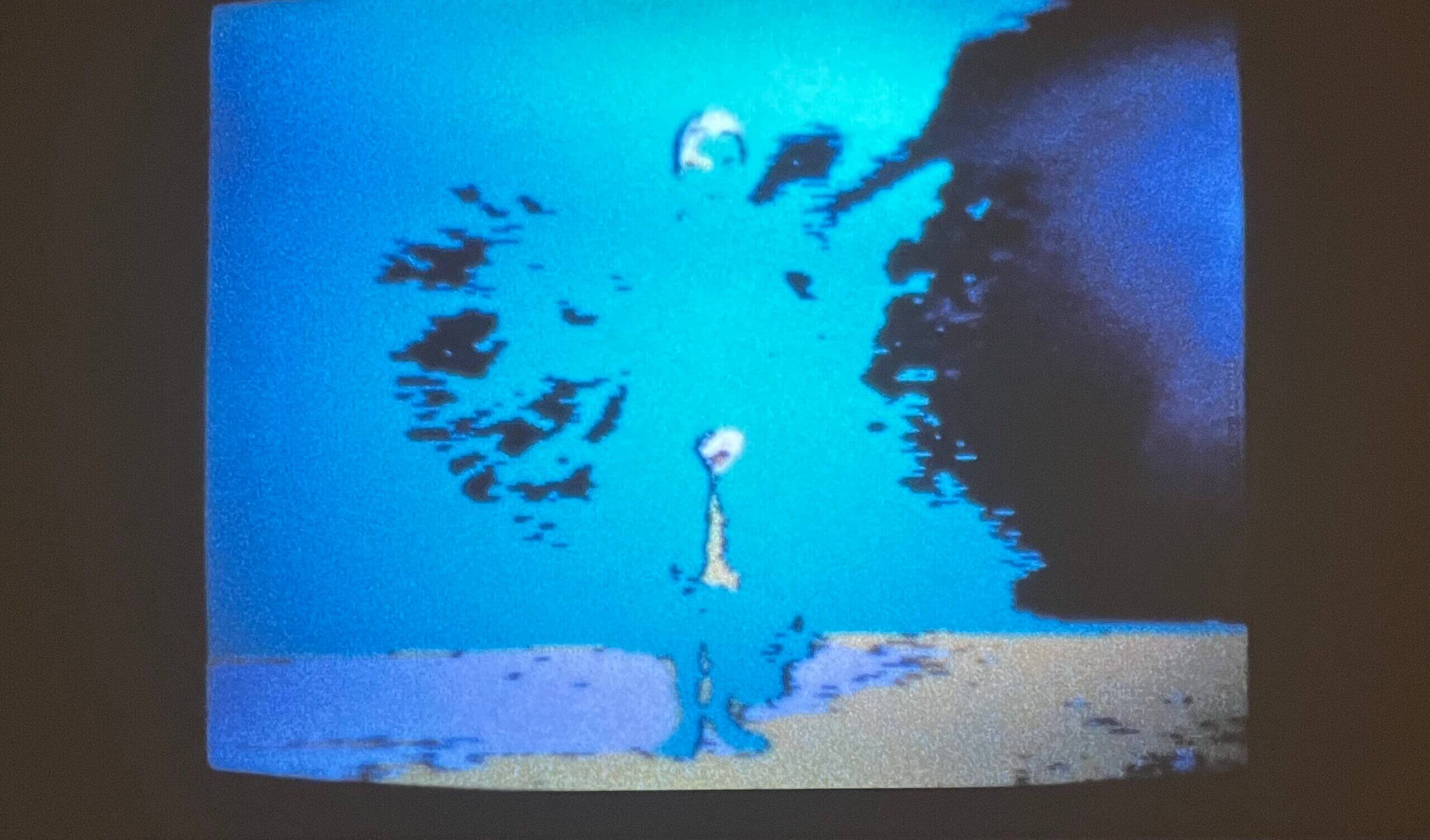

Cuban performance artist and activist Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) is also represented with Butterfly (1975) where through visual effects, she creates a spectral figure sprouting wings, re-establishing the bonds that unite her to the universe such as with her Silueta series (1973–1980). “As non-white women, our struggles are two-fold” Mendieta wrote in a curatorial statement for an exhibition of women artists of colour titled ‘Dialectics of Isolation’ (1980): “This exhibition points not necessarily to the injustice or incapacity of a society that has not been willing to include us, but more towards a personal will to continue being ‘other’.”

The Whitechapel’s efforts in re-establishing women artists in a truly intersectional manner will hopefully set the tone for all future survey exhibitions. Only when considered globally, and as a community rather than separated by Western and Non-Western parameters, will we achieve true equality of representation in a major way and in one that truly counts.