Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

“Floating Sea Palace by Lap-See Lam (b. 1990) is the first-ever institutional exhibition of the artist’s work in the UK. The commission develops from Lap-See Lam’s presentation for the Nordic Pavilion at the 60th Biennale di Venezia, 2024.”

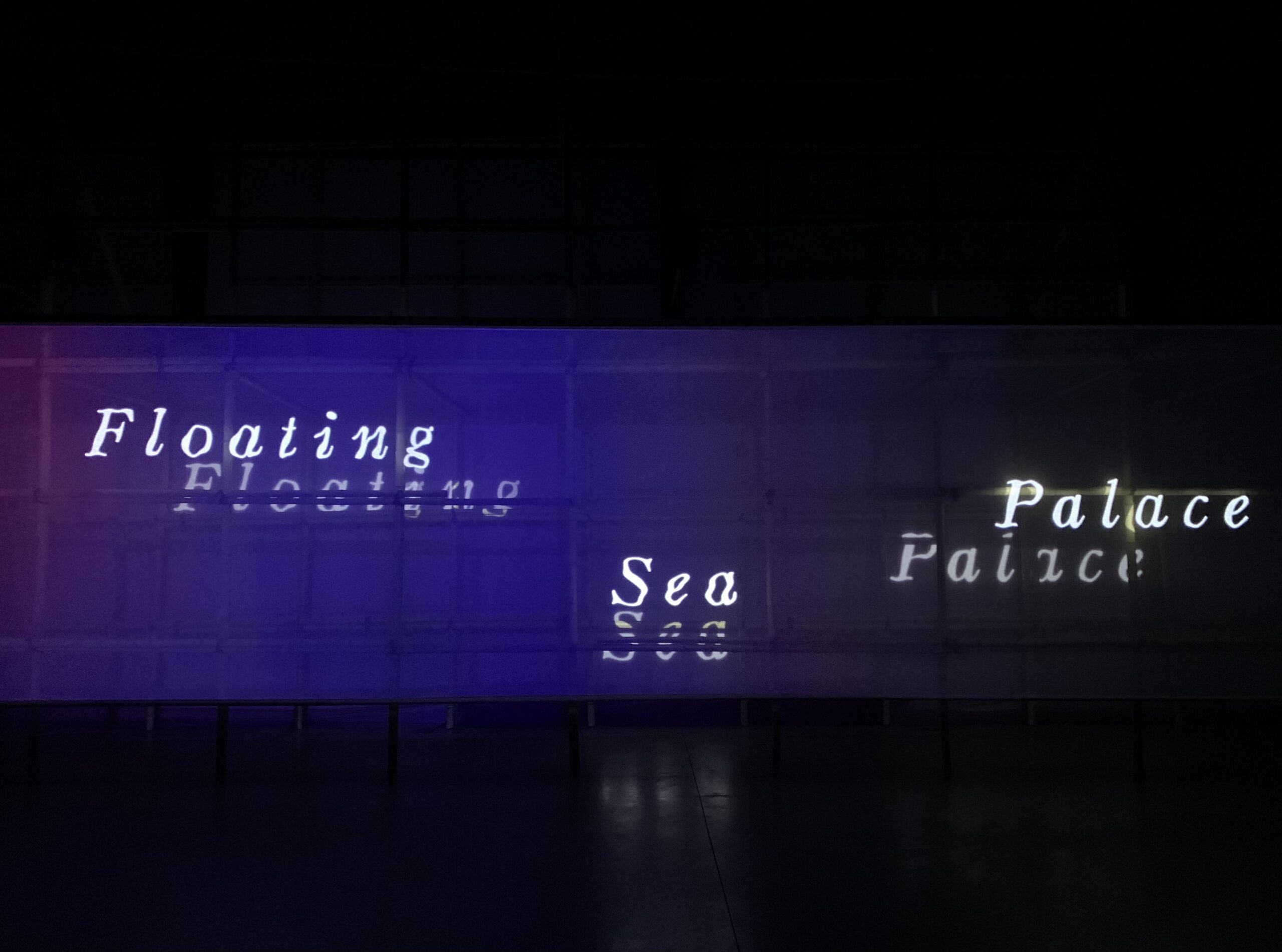

“I work in a […] a world-building universe” Swedish-based artist Lap-See Lam (b.1990) shared in an interview this year. This is precisely what the artist achieves in Floating Sea Palace, an immersive video installation that transports its viewers into her hauntingly poignant exploration of the Cantonese diaspora. Lam’s “world” is intricately layered, both in the literal sense, in the physical presentation of the exhibition space as well as the symbolic sense, in its depictions of cultural identities, displacement, heritage, and loss. The exhibition is physically situated within Studio Voltaire’s distinctive chapel gallery; in the space, Lam creates a large-scale immersive installation of bamboo scaffolding, enveloping the projection of her video work. The use of bamboo scaffolding is drawn from Cantonese Opera – in which, the very same structures are used to form temporary opera houses and stages. It is interesting to think through the space as it pays homage to this artistic heritage while at the same time embodying a diasporic displacement, as the traditional opera house is transported beyond its context of origin, into the London-based gallery.

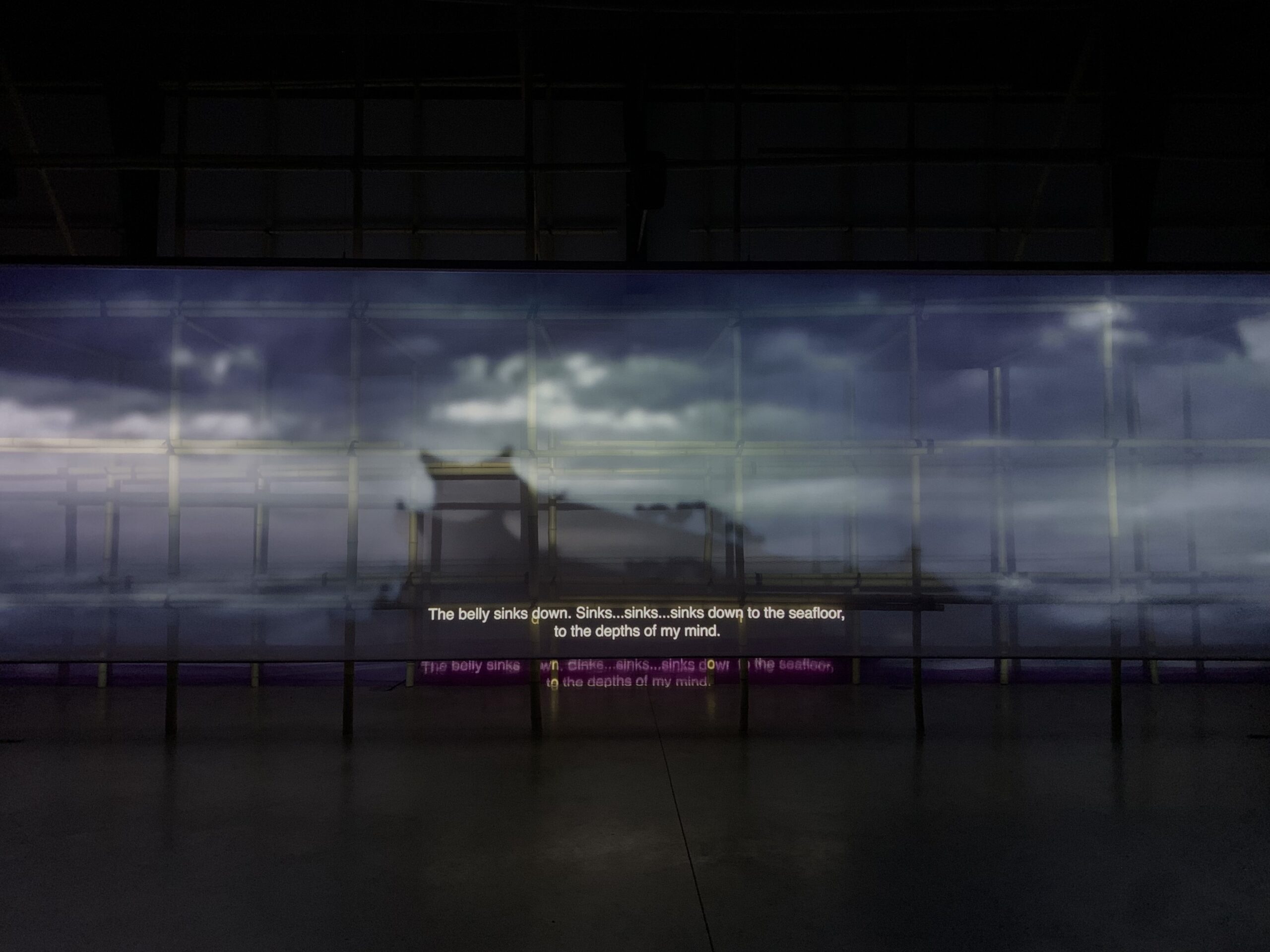

A translucent screen is positioned within this bamboo structure, serving as a medium for the video projections; the screen has a gauzy, semi-transparent quality, allowing light to pass through partially while also capturing diffused images on its surface. The interplay between the bamboo structure and the projected light is central to the installation’s visual impact. The light projections pass through the screen, casting soft reflections of the bamboo grid that are layered onto the screen itself. This effect blends boundaries of space, as elements of structure and image merge and diverge, creating a subtle visual tension between the rigidity of the bamboo and the fluidity of the projected light.

Floating Sea Place continues a cycle of works inspired by the real setting of the ‘Sea Palace’ a three-story floating Chinese restaurant in the shape of a dragon. As the exhibition text reveals: “The ‘Sea Palace’ was commissioned in the 1990s, sailing from Shanghai to Europe and later docking at Dreamers’ Quay in Gothenburg. Facing economic challenges and decay, it was eventually repurposed as a haunted funhouse at the Gröna Lund amusement park, where it was described as ‘A ship from the Orient with a thousand-year curse.’”

The central film “unfolds from the ‘Sea Palace’s’ hybrid spaces – at once a restaurant, horror house, and vessel – combining its rich past with magical elements that draw inspiration from Cantonese Opera. Each of the performers within the film enacts a specific story relating to the history and imagined future of the Cantonese diaspora, led by the character Lo Ting, a mythological fish-hybrid figure who is believed to be the ancestor of the Hong Kong people.” The layered dimensions of the ‘Sea Palace,’ as Chinese restaurant, horror house, and vessel, are significant to Lam’s exploration of diasporic identity.

In a conversation with art writer Rebecca Liu, Lam makes reference to the “chinese restaurant that only exists outside of China” that is, a “Chinese restaurant with a menu and interior design that has been very much adapted to the Western gaze.”

This understanding of the performative Chinese restaurant is also tied to Lam’s personal experiences, through her grandparents’ establishment of the ‘Bamboo Garden’ restaurant upon their arrival from Hong Kong in the 1970s. The Chinese restaurant, in and of itself, is a site riddled with contradictions – simultaneously a transmission of cultural heritage and a performance for the Western gaze, both an alienating interpretation of tradition and an integral thread in the generational and communal fabric of the Cantonese diaspora.

The horror house is a particularly evocative image through which the diasporic experience can be portrayed. The notion of ghosts, of hauntology as a framework, speaks to the lingering presences and unresolved pasts that continue to follow individuals, removed from their places of origin. Memories of the homeland – or the spector of an imagined, idealized homeland – pervade everyday life. In Lam’s work, this spectral presence manifests on various levels: through the visually ghostly overlays of fabric, projections, and shadows; the echoes of mythological figure Lo-Ting, in their past and future forms; the fragmented narratives and

histories.

The past is neither fully gone nor wholly present but occupies a liminal space within the work; the diasporic self, too, is haunted by what was left behind, yet never fully severed from it. The ship is often considered an agent of progress, of the literal movement that drives the diasporic experience. The ‘Sea Palace’ however, complicates this characterization of the vessel. As its origin story would reveal, its function as a vehicle of transportation was obviated in its later repurposing as both a horror house and restaurant; there is a resistance to the idea of the ship as simply directional and free-sailing. In Lam’s film, the ship eventually sinks after the dragon head and tail of the vessel break and fall into the water.

In Cantonese, the narration echoes, “The belly sinks down. Sinks… sinks… sinks… down to the seafloor, to the depths of my mind/ The ship is trapped. The end, my dear, a foolish rift in time./ The end, my dear, a foolish rift in time.” The image of the sinking ship lingers on the screen – it is clear that loss is intricately tied to movement in the film. The ship’s gradual disappearance prompts viewers to meditate on this very feeling of loss. What is made forgotten, absent, left behind in the diaspora? The overall effect of the film is destabilizing. Lam’s depictions of space, of characters, of narratives all reject frames of certainty or coherence. The ‘Sea Palace’ takes on varied meaning in its functions as restaurant/horror house/ship. Lo-Ting, in their fish-human hybridity, speaks to an in-betweenness of being, that reflects the same multiplicity of the diasporic identity.

The film oscillates between monochromatic shadow-play animation and vibrantly saturated frames; the audio also shifts, from Lam’s father’s Cantonese narration to performer Ivan Cheng’s poetic delivery of Future Lo Ting’s lines, to jazz musician Sofia Jernberg’s improvised singing. Lam’s exploration of incoherences and layering techniques draws on the hybrid diasporic identity, a blend of influences emerging from the collision of multiple cultural histories. Hybridity serves both as resistance to monolithic identity and as a celebration of multiplicity—continually adapting, negotiating, and redefining its contours. Lam’s film and installation, while converging in their exploration of the diasporic identity, is anything but coherent. Rather, the diaspora is presented as an expansive, contradictory, elusive experience, laid out for the viewer to experience and sit through.

In her conversation with Liu, Lam expressed: “Often, I say that you don’t have to understand the work. My hope is that people feel the work rather than understanding every detail. It’s really not about that with my work.” If the artwork is centered around feeling, then Lam’s work is most powerful in conveying the tensions between loss and preservation, separation and synthesis, memory and forgetting, shaping a complex vision of identity that explores both fractured wholeness and resilient selfhood. By layering performative constructions, fragmented memories, hybrid aesthetics, generational losses, haunting presences, Floating Sea Palace immerses its viewers into the unresolved, multifaceted, and enduring nature of diasporic being.