Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Marlene Smith, born in 1964 in Birmingham, is a prominent British artist and curator. Her involvement in activism, research, and the arts is extensive, as an original member of the Blk Art Group in the 1980s and one of the founding members of the BLK Art Group Research Project. She was also director of The Public in West Bromwich and UK Research Manager for Black Artists and Modernism, a collaborative research project run by the University of the Arts London and Middlesex University. She is the Director of The Room Next to Mine, and was an Associate of Lubaina Himid’s Making Histories Visible Project and Associate Artist at Modern Art Oxford.

Smith continues to actively contribute to the work of Black artists today, using her research, writing, and art-making to address the lack of visibility in Black history and confront racist structures in society. In recent years, Smith’s work was shown as part of a group exhibition ‘The More Things Change…’ (2023) at the Wolverhampton Art Gallery, featuring the work of the founder member artists of the Blk Art Group, “an association of young black British artists formed in 1979 to question what black art was, its identity and what it could become in the future.” Not only was her work shown at Tate Britain’s successful ‘Women in Revolt! : Art, Activism and the Women’s Movement in the UK 1970-1990′ later in the year, she was also a key consultant for the curatorial team. Smith’s newest solo show ‘Ah, Sugar’ is also currently on show at the Cubitt Gallery until 18 October 2024.

(See RAW’s 2023 interview with Linsey Young, Curator of Women in Revolt!: https://r-a- w.net/blog/interview-with-linsey-young-curator-at-tate-britain-on-show-women-in-revolt/)

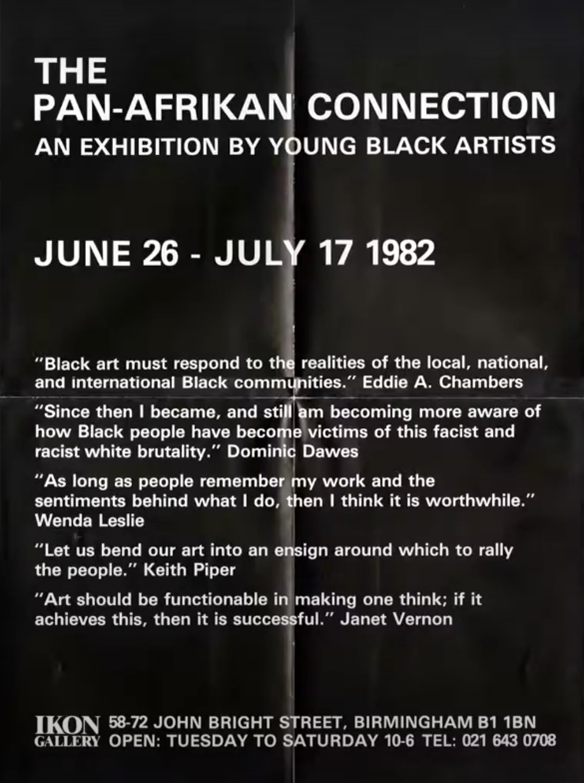

While Smith’s contributions to Black representation, history, and the art scene are widely recognised, perhaps fewer are familiar with the artist’s personal stories, experiences, and processes of art-making, as they have evolved and changed over time. In a 2021 public lecture Black British Artists and Political Activism: ‘She is not Bullet Proof’ under the Paul Melon Centre for British Art, Smith shared her early experiences as a budding artist and a member of the Blk Art Group: “When I was doing my A-levels at school, I’d been researching into […] black art and black artists […] my teachers at school were really worried that I wouldn’t be able to find any material because they didn’t know any black artists. So there was almost this feeling that I wouldn’t be able to find any black artists because they didn’t exist […] but I found material about the black arts movement in the US, the 1960s to 1970s movement that happened there. And so most of the writing I did during my last year of A-levels was about work that had happened in US context.” As Smith continued her research, she gradually began to find other UK-based black artists based in Birmingham, such as Vanley Burke. Upon hearing about an auction organised by the London School of Economics at the time, she also attended the show, and through it, made contact with artists such as Frank Bowling, Ronald Moody, and Shakka Dedi. It was around the same period of time in 1982 that Smith attended an exhibition that would soon become a cornerstone moment in her art journey. The Pan-Afrikan Connection: An Exhibition by Young Black British Artists, held at the Ikon Gallery in her hometown of Birmingham, was organised by a group of Midlands-based art students who had come together initially as the Wolverhampton Young Black Artists before becoming the Pan-Afrikan Connection and eventually the BLK Art Group. In an anecdote, Smith shared “One Saturday morning, my mother dropped this envelope into my bedroom […] When I opened it, I found [the exhibition] poster folded inside. What I hadn’t realized was that my mother was working with Keith Piper’s father […] in the same hospital […] I can only assume that they compared notes about their wayward children and how difficult it was raising children in the UK and found that we both had this interest in art. Because the poster was addressed to me, I think that was Keith Piper’s father who sent me that poster. And so, I went along to the Ikon Gallery, which is a gallery I knew very well. I met Keith Piper there, and he was the only member of the Blk Art Group that was actually at the opening. He literally had white paint on hands because he’d just finished installing the work when I got there. That was how I got to meet [the group].”

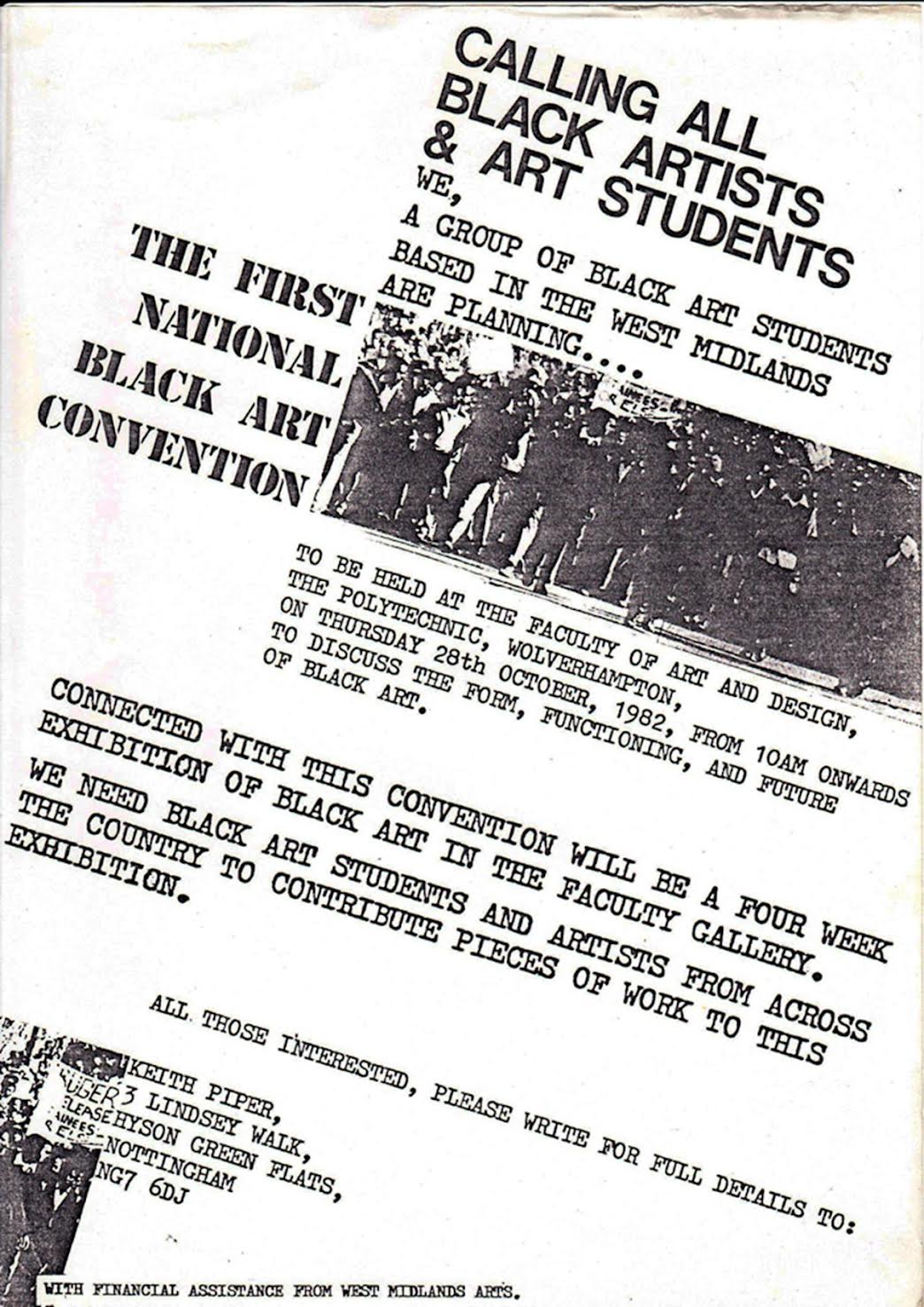

“The point about the poster is that I’ve read lots of radical black statements related to the black art movement in the US […] and got very excited by the prospect of those types of radical aesthetics. But what happened when I opened the poster was that I was reading the same types of statements, but this time they were made by young black people from the same kind of background as me. And I realized that there was something happening right there and then, in proximity to me, and that made me really excited. So, I remember very well that the hairs on the back of my neck stood up when I read this poster.” Soon after, in October of the same year, the Blk Art Group organised the first national Black Art convention at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in October. Reflecting on the monumental moment, Smith expressed, “Similar to me, lots of young art students found themselves in art colleges where they were the only one. The calling of all black artist and art students is just a tantalizing possibility of community. Just as I had happily and gleefully leaved through books about what the radicalism of the black artist in the US and then got really excited when I finally met some young black artists my own age and background, I think that call lit a fire under people who wanted to be in a community and have peers.”

While Smith’s introduction into the Blk Art Group brought her into contact with an important network of black artists, she continued to seek deeper knowledge of black histories that informed both her understanding of the world and of her art: “I would say that my politicization came through just being curious and wanting to know more about my own

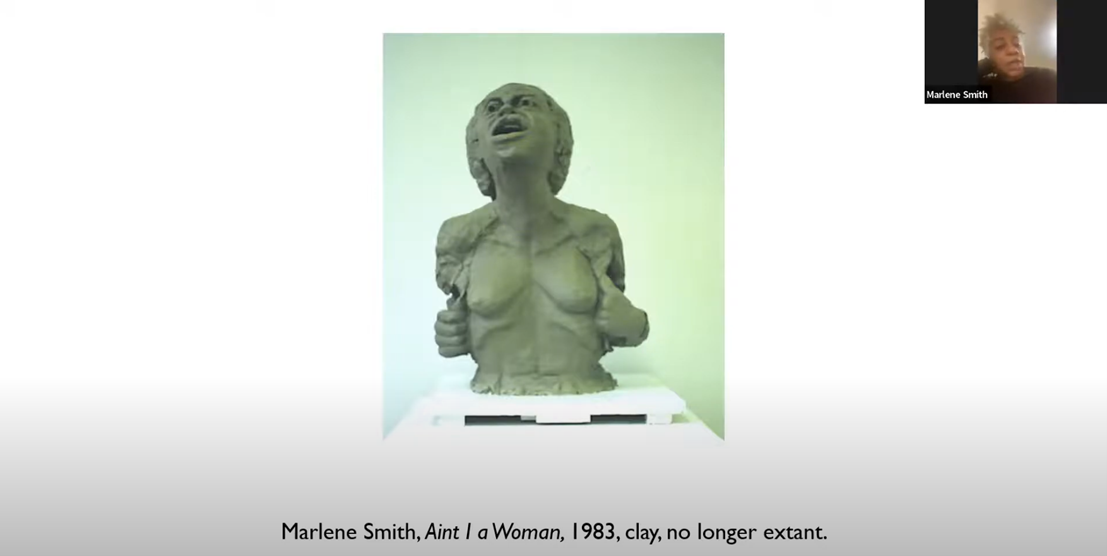

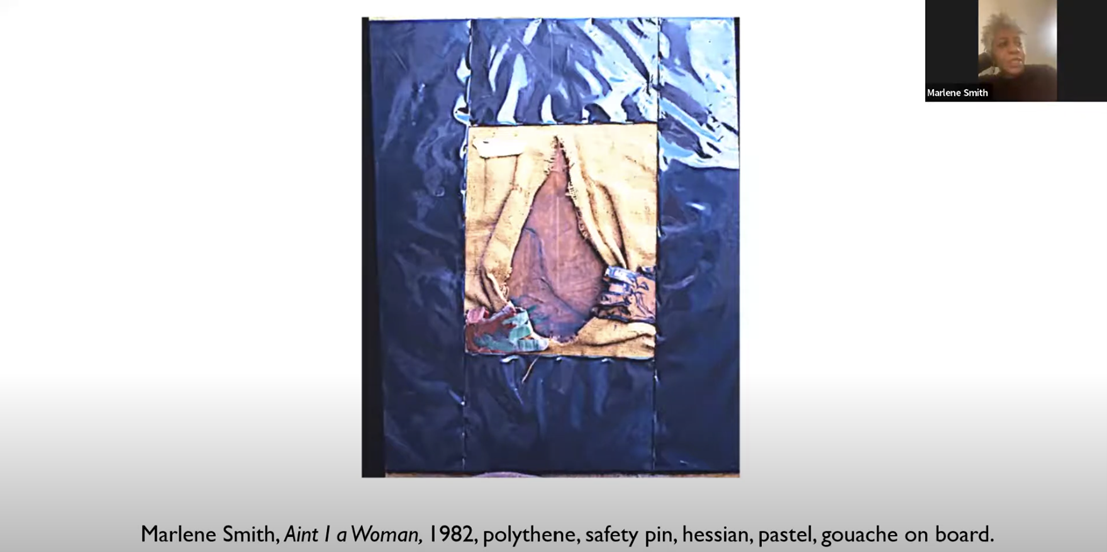

history. And I started this habit of going to a black bookshop that was not far from where my school […] And because I wasn’t on a course or being tutored by anyone, I literally used to wander around the bookshop and look at book covers and titles and then decide based on the titles and the cover of the book whether I was going to read it or not.” This process prompted Smith to create one of her early series of work, titled Ain’t I a Woman (1982-1983), inspired by bell hook’s book of the same title. Smith recounted “One of the things I read in that book was a story about Sojourner Truth. And Sojourner Truth was an abolitionist and a feminist, and there is a famous story about her at a rally for women’s suffrage. She tore open her blouse and revealed her breasts, and she made a speech where she was kind of saying, ‘I’ve had to work side-by-side with men, ain’t I a woman?’ […] I became obsessed with this idea that a woman should stand in a crowded room where she would have been faced by, I assume, a lot of white people, where she would have been intimidated by them[…] I’m just so moved by the idea of this woman who was born in slavery, who’d endured so much during slavery and who was advocating both abolition of slavery and universal suffrage […] I was so impressed by her and taken with this moment that I made several pieces of work.”

Smith’s sensitivity to representations of history across varying artistic mediums is already evident at this stage of her career; the use of the historic archive as source, in particular, is and will continue to be an important thread in her artmaking. This is perhaps most clearly present in Smith’s notable Art History (1987), currently in the Sheffield Museum’s collection for instance. The work can be viewed in two parts: the first being the disparate collection of four archival images on the right. The images include a photograph of a painting by artist-painter Simone Alexander as well as a black-and-white photograph of a ceramist at work – or in Smith’s words “a collection of black women who have made or are making work.”

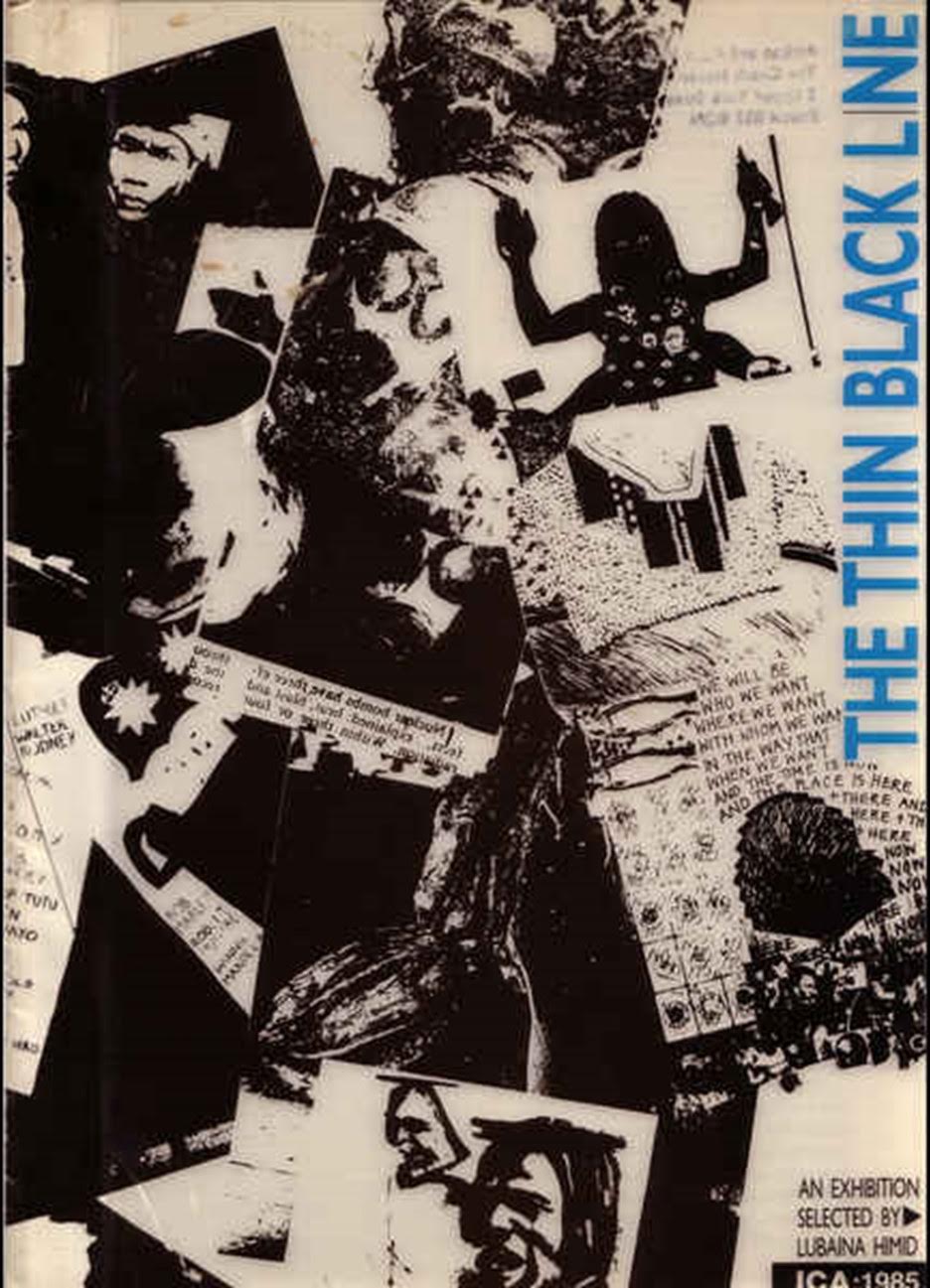

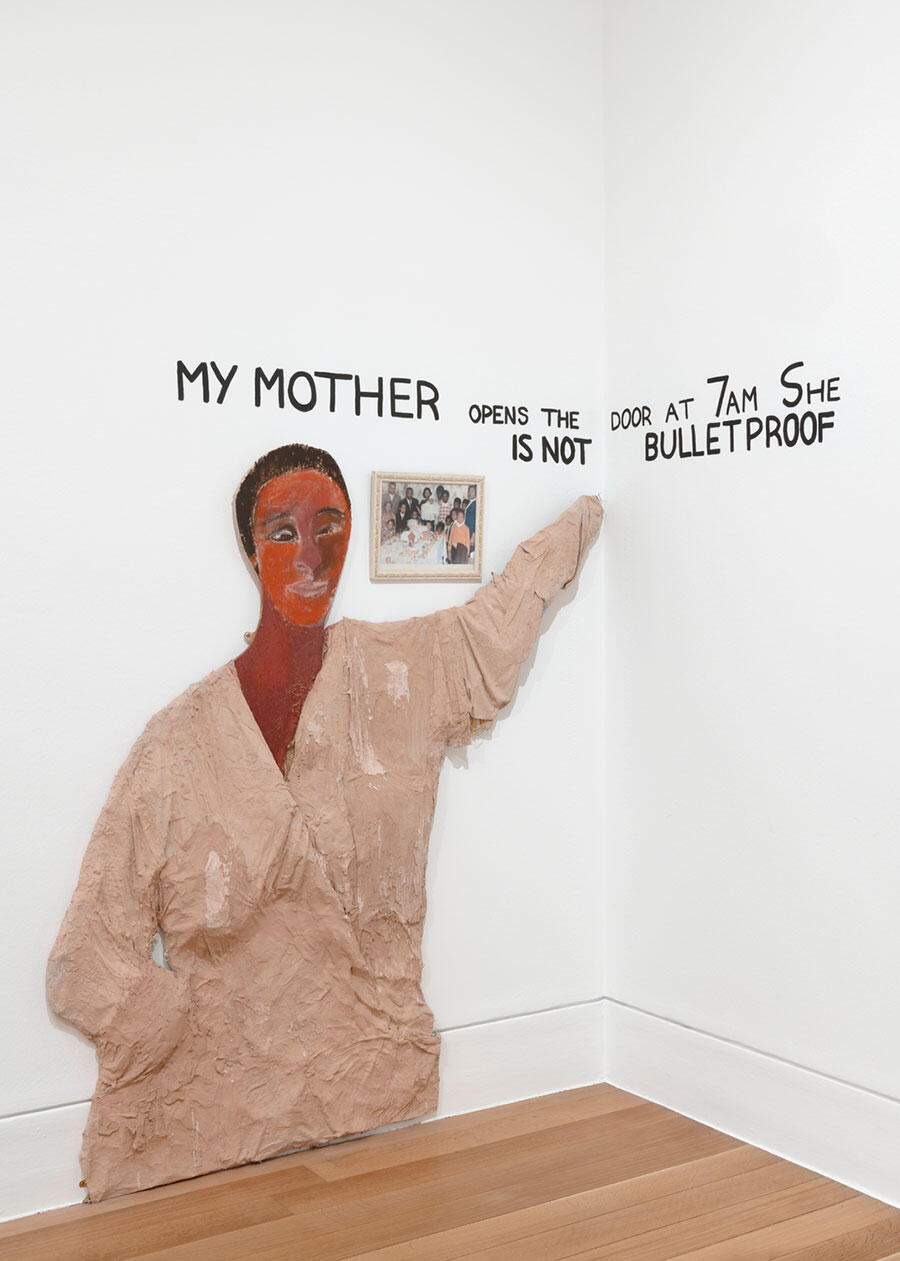

The second part of the work includes the three-dimensional installation of the vase on the left. In a podcast series titled Living Archives, co-produced by Stuart Hall Foundation, International Curators Forum in 2023, Marlene explained, “The main part of the piece is a crocheted vase covering, which I asked my mother to make for me. And then the vase covering when it had been crocheted, she gave it to me in two pieces so there’s a handle and then there’s the vase itself. And she said, ‘Right, you need to stiffen them now before you put them into the vase’, and I was like, ‘Okay, then I'll get some starch.’ And she was like, ‘No, no, no, no, no, you don’t stiffen them with starch. It’s a sugar and water solution that you use.’ […] I’ve been around these types of iconic house decorations all my life up until that point, and I hadn’t realised that it was sugar and water. And that just opened up a whole new realm of discovery for me in terms of thinking about sugar and water. How sugar from the plantations, and the whole history of sugar in relation to my mom, and to me, you know, that legacy, that post-slavery connection.” Considerations of materiality, in this case, become heavily imbued with a new sense of meaning, in relation to black history and identity – artistic manipulations of sugar make a reappearance in Smith’s current practice, as a central component in her solo show Ah, Sugar (2024). Another notable piece by Smith, that has once again gained prominence due to its reproduction and showing in the recent Women in Revolt! show is Good Housekeeping I, first made for the ICA exhibition The Thin Black Line in 1985. Smith made the work during the time of much social-political unrest and upheaval, as she was participating in marches, in protest against the Cherry Groce shooting and policies around apartheid and immigration.

Good Housekeeping I includes a family photograph in the background. It is an image of a woman up against the wall, with the words, “MY MOTHER OPENS THE DOOR AT 7AM. SHE IS NOT BULLEPROOF” written across it. “And it was really a reference to Cherry Groce. And the shooting of Cherry Groce. Cherry Groce is a woman who opened her door to

the police early one morning: they had a warrant, they were looking for her son, and somehow (and it’s never been explained how this happened) in the pursuit of her son, they managed to shoot her and she was in a wheelchair for the rest of her life. So, I made that piece back in 1985. Unless you know my family, you wouldn’t know this, but I did actually fashion the image of the woman against my mom. I have constantly in my work made reference to that generation. I’ve done that because I just I want to talk about now, but you can’t talk about now without knowing the history of now.” The ”now” Smith refers to is significant, when one considers the recent shift towards showcasing Black and female artists in mainstream art spaces. In a 2023 podcast Women, Art and Activism with BBC Radio, Smith spoke of her involvement in the Women in Revolt! exhibition, as both a contributing consultant and artist: “I just felt that it was really important given my background and history and expertise that we should have as diverse a body of work as possible and I was really pleased that Lindsey and her team at Tate were really open to that. I suggested some artists that might not have been prominent enough to be on Lindsey’s radar, and whenever I did suggest an artist, I was really pleased to see that she would do a studio visit, taking her assistants with her. It was always a group of women talking about the work. There are [now] a number of artists that are showing work that may not have (I can’t be sure) but that may not have been included if I hadn’t been on the advisors team.”

In regards to showing a reproduction of her own work, Smith shared “It was really interesting actually because what happened was, I had a studio conversation with Lindsey and her team, and we were talking about Good Housekeeping.” And she asked whether they would be able to show it, and I said “No, unfortunately, you can’t show it because it’s long ago disintegrated. It was Lindsey who put the idea in my head to remake it, and I’m so grateful to her and her team for suggesting it because I don’t think I would have thought of it. And in terms of what it took, to begin with, I was just buying and trying to acquire the same materials.” Good Housekeeping is made of a chipboard panel that is cut into the shape of a woman. Then on top of the chipboard panel is chicken wire that creates a structure. Then on top of the chicken wire is household plaster. The jay cloths are soaked in the plaster and draped over the chicken wire to build the body. I could remember that I used those materials, but I haven’t used them since, so it was a real learning curve to just remember how to manipulate materials in the right way. By the time I got to the plaster part, I was so enjoying myself. The feeling of immersing my hands in the warm – there’s something about the chemistry of household plaster, when you add it to cold water, it generates heat – and I just remember squelching the plaster between my hands and how it felt layering it onto the figure. I really enjoyed the process, and it made me think that I might of ahead and reproduce some other works of mine. Back in 1982 or 1985, I wasn’t thinking about legacy in the sense of keeping hold of the work, I thought of the work as speaking once to an audience about a particular theme and moving on to the next theme. But this experience has made me think again about what it might mean to remake other pieces.

Smith’s current exhibition at the Cubitt Gallery is her first solo show in her artistic career of over 40 years. As the exhibition statement elucidates, Smith’s newly commissioned photographic and sculptural work demonstrates the artist’s ongoing interest in the material and bodily qualities of artistic practice. Thematic explorations of the archive, generational memory, and materiality – perhaps most clearly paralleled in Art History (1987) – are once again present in this body of work, though this time in its matured form. “The works present act as inquiries into the cyclical nature of social histories and familial entanglements. In a body of three-dimensional work developed with Smith’s inherited collection of textiles, impressions and imprints are made from adornments, table settings, and her parent’s own wardrobes, which are visible in a series of iced sugar sculptures. Textiles appear again as materials that interact with the human body in a series of portraits, abstracted through close looking and performative gestures, that Smith has developed with friend and long-time collaborator, Ajamu.”

In a community viewing of the show, Curator Seán Elder drew viewers’ attention to various components of Smith’s work. The distinct height of the silver exhibition platforms, carefully chosen to match the height of furniture – a coffee table, kitchen counter, dining table –in the domestic space. The imprint of lace adornments visible on the sugar sculptures – a visual reminder of the common West Indian home.

The photographs were printed on bagasse, a byproduct of sugarcane processing. The close-up images of Smith’s body, were created and memorialized in a collaborative process with fellow artist Ajamu. The result is a delicately beautiful narrative of Smith’s black identity, heritage, community, and history.

Smith’s legacy and contribution to Black representation, through art, activism, research, and writing, is evident. Speaking on her journey as a Black artist today, Smith stated “[As a] black woman [artist] you want to have visibility because visibility has been denied you for so long. But on the other hand, you don’t want to be constantly standing in for every black woman. I think that’s a really difficult path to walk and it’s really quite tricky for women of any age group.” However, there is mostly an air of optimism and potentiality, as she reflects on the trajectory of black art today: “I mean, I’m always surprised and delighted when I go to speak and I see and meet young black women artists [today]. There just seems to be loads of them, and I’m really happy about that […] in the 1980s, I felt like I knew all the black women artists and now that I’m in my 50s and it’s now 2023, I don’t know all the black women artists. And that is a real point for celebration.”