Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

‘We touch things to assure ourselves of reality. We touch the objects of our love. We touch the things we form. Our tactile experiences are elemental… We will learn to use grain and gloss, smoothness, roughness…’ Anni Albers, Tactile Sensibility, 1965

German textile artist Annie Albers’ (1899-1994) exploration of ‘tactile sensibility’ evokes the ancient craft of the lapidary artist. The year these words were published, Charlotte de Syllas (born 1946) was a jewellery student in London. Now recognised as the foremost gemstone carver in Britain, de Syllas has spent the last 60 years working the unrelenting material into impossibly soft and elaborate forms. The gemstones of de Syllas’ craft are elemental, they are products of a geological, deep time and embody a premodern lithic, material imagination. How the light passes through an opal relates to its water content, the presence of iron pyrites in deep rich blue lapis lazuli form celestial gold flecks, spinach green jadeite or pale creamy nephrite jade is mined from the earth and gathered up from the landscapes – it is these elemental origins that resonate in de Syllas’ jewellery.

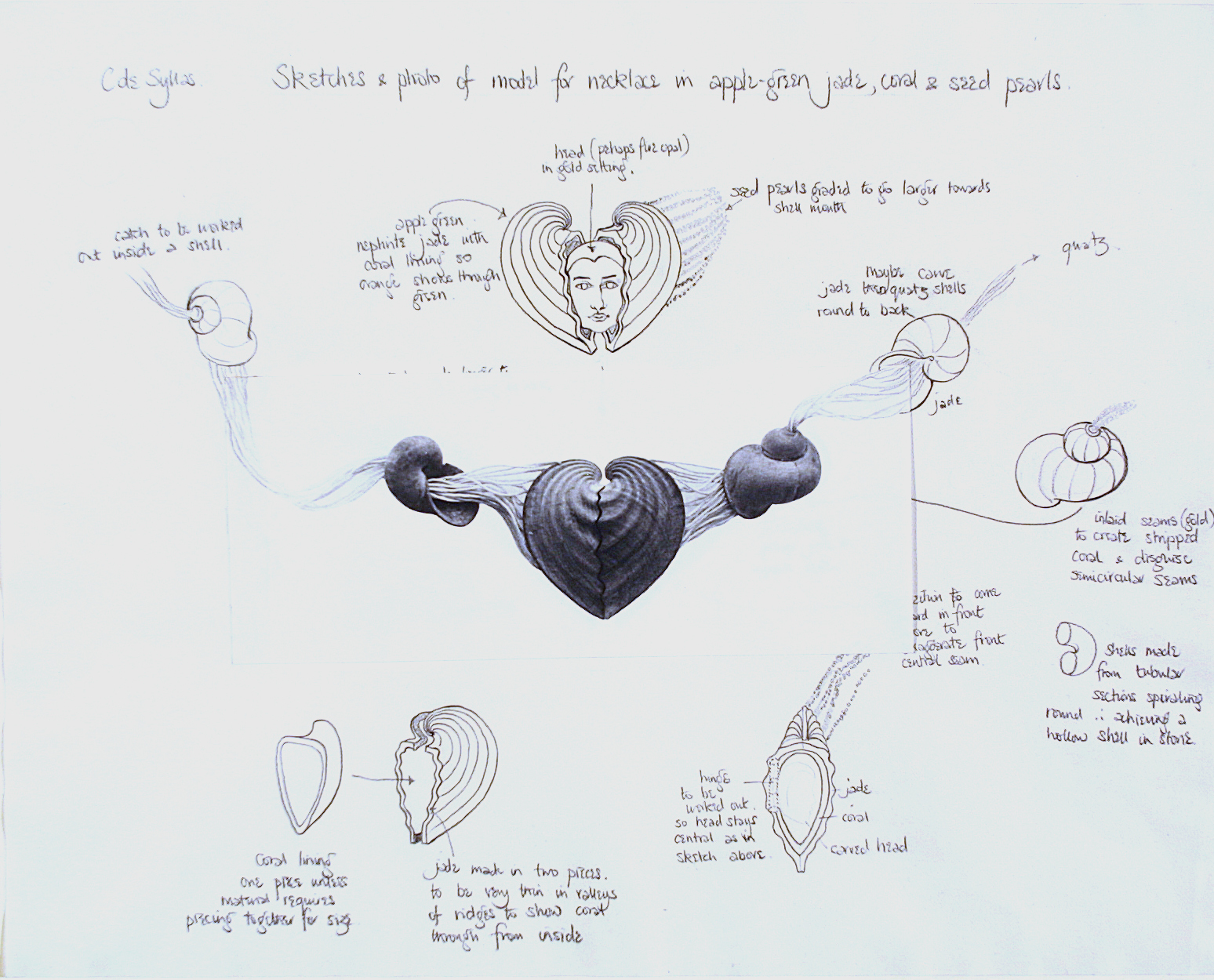

The flowing contours of her carvings make mineral malleable in bespoke pieces from rings to necklaces. The forms recall ridged shells, secretions, ripples, cocoons, the growth rings of trees, sedimentary layers or the undulating ridges on a sandy shore heft by the gravitational pull of the ocean tides. For a necklace completed as a commission for the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1989, de Syllas carved four shells from green nephrite jade, white jadeite and coral, that were threaded together with dyed silk strings strung with tiny luminous seed pearls – it is an aquatic feast of stone marine forms and precious organic materials cultivated by the sea.

De Syllas wasn’t always a stone carver. In the period between 1964-66 the Goldsmith’s Company acquired 20 pieces of her student work made during the years she spent on the pioneering degree course at Hornsey Art College lead by avant-garde jeweller Gerda Flöckinger (born 1927). These pieces show de Syllas’ visionary flair for sculptural forms as well as her skilful command of a range of traditional jewellery techniques: a silver bangle made in the 1967 shows finely laminated gold that echoes the visual patterning of an inlaid abalone shell. Over the years she has pursued research of other innovative materials such as the fiendishly tricky fine glass casting of hollow forms, lace beading soaked in porcelain and the cutting of synthetic rubies and sapphires. However, it is predominantly the art of stone carving that de Syllas has made her life’s work.

Flöckinger taught de Syllas to carve gemstones in cabochon form, planting the seeds for her to teach herself basic gem carving skills from a book on the subject. De Syllas credits her jewellery training for her ability to design three-dimensional jigsaws in stone that place contrasting colours together. The white and black nephrite jade forms of the ceremonial, ‘Millenium’ bracelet (2000), showcase this sensibility. The tessellating swirls nestle together in a perfect fit and yet at the same time, the bracelet is an homage to the fractious nature of stone when it breaks in two.

With an architect and an illustrator/designer for parents, de Syllas was brought up in a post-war modernistic artistic milieu. She wanted to be a jeweller from age 14 but in 1963 was inspired to seek formal training after seeing an exhibition of George Braque’s art jewellery. Her parents work and association with a modernist aesthetic seemed to propel de Syllas towards something different, forms that were less abstract and more stylised and natural. Dynamic motifs appear throughout her oeuvre, which is teeming with figures, birds in flight, insects, aquatic life and river and sea plants. It is jewellery designed to be lived in. The stone pieces are excavated from within so that the elements put together are light, ergonomic and smooth against the body. Her designs are usually bespoke commissions inspired by the people they were intended for (even the V&A shell necklace was created for an imaginary person). She intends the pieces to reflect the wearer’s personality, lifestyle and complexion.

The original owner of the ‘Magpie necklace’, liked to wear blue, black and white. The two magpies of the old folk rhyme one for sorrow two for joy…’, meet at the centre of this winged necklace, flying in opposite directions. It has been expertly carved from 27 elements of black Wyoming nephrite jade, with the addition of blue-green-petrol-sheen labradorite veneers that catch the light on the tail feathers and wings. There are flashes of white jadeite too.‘The flexible joints of the wings mean that the stones slices undulate in tandem with the movement of the body. The stone pieces are assembled via a neat little bit of engineering using hand-dyed and woven silk braids (made by long time collaborator, Catherine Martin, a jeweller a specialist in the ancient Japanese art of braiding, Kumihimo, who has fabricated the silk strings for many of de Syllas’ pieces). De Syllas’ joyful approach to necklaces, because they allow the most space for carving, is evident in the ‘Magpie’ which took over four years to complete.

De Syllas incorporates her own tacit knowledge of stone’s resilience into her creations. Gemstone carving requires technical skill as well as a knowledge of the way the different materials behave under pressure. The relative hardness of different stones dictates how they can be cut. Nephrites and jadeites are some of de Syllas’ favourite stones to carve because of the way the crystalline matrix feels when it is worked with tools. Other stones, like rock crystal, have different qualities that a carver needs to understand to be able to abrade and polish them without causing the piece to splinter and break. Sourcing the stones is important and she will take time to source the right colours in the right quality without internal flaws that make them unpredictable to carve. Modelling the forms in soft, boxwood and briar root wood before approaching the stone is essential to the design process.

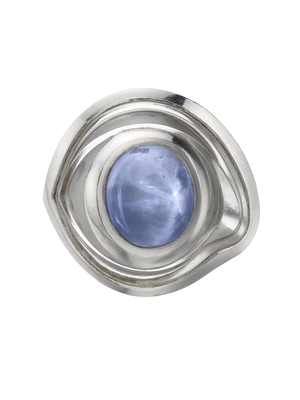

A bespoke box to store the jewel in is often a pendant part of de Syllas’ artistic output. In her first major commission, ‘Bobby’s Ring’, she carved clasped hands in wood and gold leaf to form the protective vessel for a chalcedony ring of a human head. Looking back, de Syllas has noted that after this commission ‘combining the technical, the aesthetic and the personal in an original design came to be my aim in all future work’.

Whilst sometimes a design idea sets her on the hunt for the exact stone she needs, other creations are a result of living with a gem on the workbench for many years, getting to know it and waiting for the right pairing of personality to raw material such as fiery pink tourmalines she purchased at a fair in France that eventually made a pair of rings for two red-headed daughters of a client. She has occasionally incorporated stones with ancestral or emotional significance for the wearer, though the inclusion of faceted jewels in her jewellery is extremely rare. In such instances, she is at pains to make clear that it was a very special favour. As seen in a rose cut diamond in a ring shaped like an eye, that once belonged to the owner’s mother. De Syllas agreed to include the diamond the condition that it was placed face down. Orientated this way, it becomes like a kaleidoscope lens with the theatrical architecture of the cut revealed (designed to make the stone sparkle when set traditionally).

Charlotte de Syllas still lives in Norfolk where she has her studio and teaches gemstone carving. Image source: Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (Qest) https://www.qest.org.uk/qest-award-for-excellence-2022-presented-to-charlotte-de-syllas/

Dr Sophie Morris is Curator of The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. She is interested in making and materials especially historic stone, mosaic and metalworking as well as artists working with endangered ancestral crafts today. Recent projects she has contributed to include the exhibition, ‘Eternal Medium: Seeing the World in Stone’ at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (August 2023 – January 2024) and a V&A video, ‘A brief history of powerful gemstone amulets’. She is currently co-editing a collection of essays on the representation of earth, air, water and fire entitled, Elemental Forces in Early Modern Culture 1400-1700 (forthcoming Amsterdam University Press, 2024).