Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

In their traditional form, sirens are gendered female, impossibly desirable, and deadly: the Freudian embodiment of sexuality. In The Odyssey, the story goes that Odysseus escaped the lethalness of the siren’s song by being tied to the mast of his ship while his men plugged their ears with wax. Consequently, the sirens drowned themselves as they were so distressed to see a man detect their song yet escape death. In 1976, the French scholar Hélène Cixous famously reimagined the gender of the mythical siren. Redeeming the siren from the Homeric tale which delegates femininity into the realm of the illogical, she posited: ‘Wouldn’t the worst be […] that women aren’t castrated, that they have only have to stop listening to the Sirens (for the Sirens were men) for history to change its meaning?’ (p. 885). In doing so, Cixous affirmed the radical potential of appropriating myth for feminist ends.

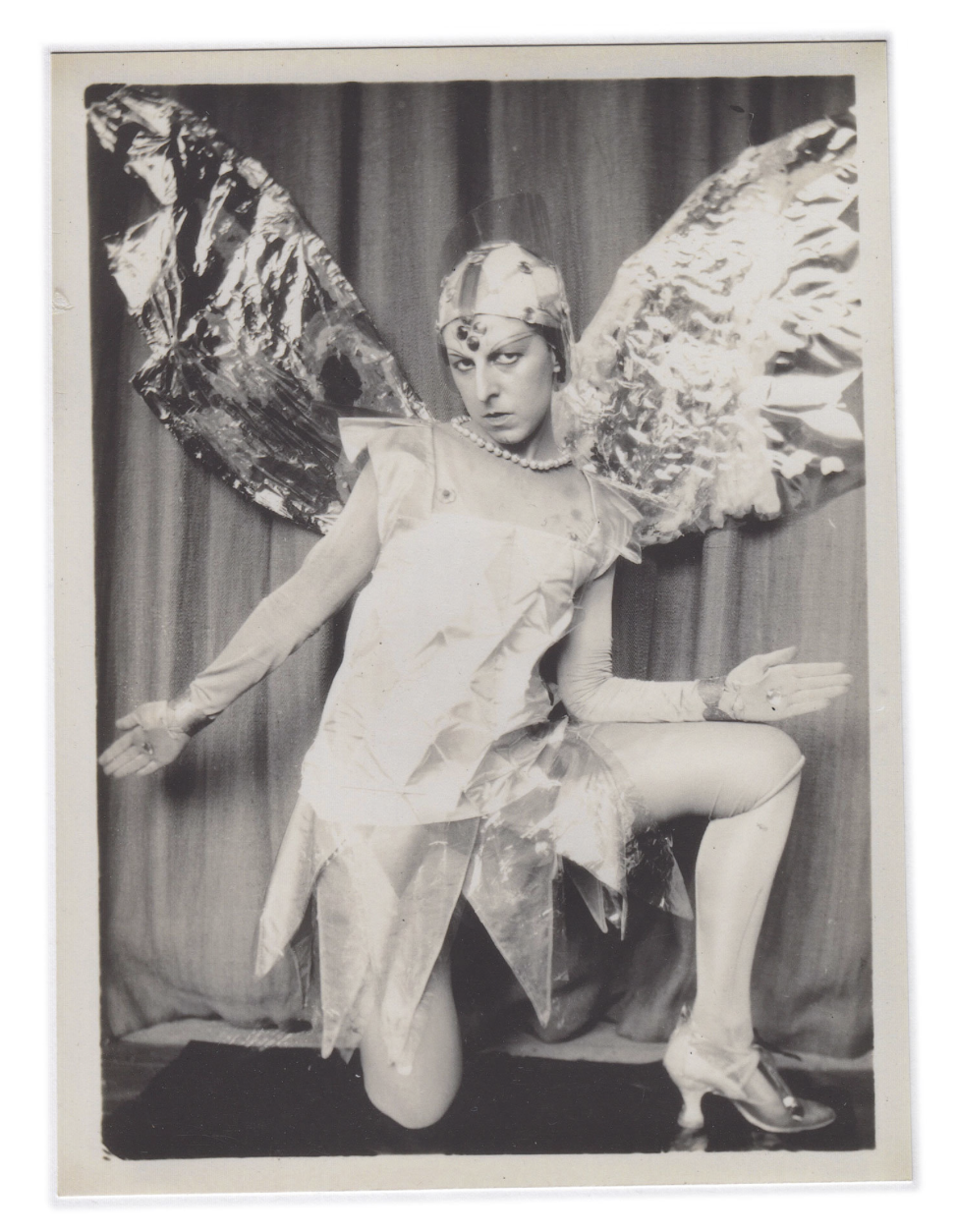

Claude Cahun, Untitled (Claude Cahun in Le Mystère D’Adam), 1929.

Claude Cahun, Untitled (Claude Cahun in Le Mystère D’Adam), 1929. In the avant-garde movement of Surrealism, sirens are consistently depicted as mermaid-like creatures, although in ancient mythology they are winged. As a symbol, the fish-tailed siren reappears frequently throughout Surrealist painting, poetry, and prose. Before Cixous, the French Surrealist Claude Cahun (1894 – 1954) recognised the siren’s capacity to challenge hegemonic forces of power. As a gender non-conforming Jewish lesbian, Cahun negotiated multiple systems of oppression. To set the scene: Cahun and their lifelong partner and collaborator Marcel Moore (1892 – 1972) were fiercely resistant. As well as coordinating an anti-fascist campaign across the island of Jersey during World War II, the pair defied the French government’s enforcement of heteronormativity during the interbellum. Moreover, it has been raised that Cahun’s presence in Surrealism brought the integrity of Surrealist leader Andre Breton’s anti-establishment politics into question. He regarded Cahun as a ‘curious spirit’ yet also as a threat; their sexuality and gender presentation unsettled Breton enough to even avoid their company.

Before Cahun relocated from Paris to Jersey with Moore, she authored Heroines (1925) and Disavowals (1930). Collectively, these texts are brimming with sapphic imagery and notably, lesbian desire often emerges in the guise of the siren. Fittingly, Shelley Rice described Heroines as Cahun’s ‘inverted odyssey’: a quest to place themselves within the ‘epic structures of human experience’ (p. 15) as they rework ancient myths which are anchored in the patriarchy. ‘Sappho the Misunderstood’, a character in Heroines named in homage of the Greek poet from Lesbos, uniquely envisions herself as a siren to challenge outdated discourses on homosexuality which restrictively regard the lesbian as a masculinised subject. Sappho the Misunderstood boasts: ‘At night – like my sisters, the Sirens, less shameless than my mortal sisters, I lure passersby, preferably the female variety, and drown them with my strong hands.’ (p. 65) Heteronormative conventions are overturned here, as the sapphic siren lures women to their death, too. In feminist alignment with Cixous, Cahun understood the power of the siren’s enchanting song as a strategy to make men listen, but even furthered the tale into sadomasochistic territory. Cahun’s ‘siren is beguiled by (their) own voice’ (Disavowals, p. 21), a fate which is at once an exploration of self-love, eroticism, and death.

It is important to situate Cahun’s sapphic siren in the wider context of Surrealism. Breton and Louis Aragon, both leading figures of French Surrealism, engaged with siren imagery in “Soluble Fish” (1924) and Paris Peasant (1926) respectively. “Soluble Fish” tells the story in which the dismembered torso of a woman named the ‘new Eve’ is swept along by the Seine. New Eve’s siren powers are implied because the boat sent out to retrieve her remains vanishes. In Paris Peasant, a siren called Lisel swims in circles while trapped inside a shop window. The concurrence of water and siren in suggests a violent denial of women’s voices and, comparatively, these anthropomorphic sirens lack the agency of Sappho the Misunderstood. While the tail of the siren can be read as a broader metaphor for women’s restricted mobility within patriarchal society, Cahun’s reworking of the myth’s deathly heterosexuality grants them a stable platform for self-expression and mythical transcendence. ‘I am a siren […] standing erect on my tail’ (p. 78), they wrote in Heroines, mocking the psychoanalyst’s interpretation of the tail as phallic substitute. If the Homeric siren struggles to survive or even move on land, the sea, then, represents a terrain of refuge and artistic freedom.

Throughout the 1920s, 30s and 40s, Cahun and Moore crafted costumes out of objects found along Jersey’s shorelines and staged many enigmatic photographs which straddle the terrains of land and water, masculine and feminine. Although mostly recorded as self-portraits in the historical record, there has been considerable effort the likes of scholar Tirza True Latimer to restore Moore’s status as collaborator. The photographs illuminate the collaborators’ identification with the sea, a body of water which is impossible to be tamed or contained. Mapped out by the movement of the tides, together they existed in a place of eternal ecological fluctuation, thereby reconnecting queer existence with nature, and defying that age-old homophobic argument that lesbians are unnatural. Like sapphic sirens, emboldened by their mutual ‘mad love’, they appropriated the seascape for queer investigation. If we remove the categories of photographer and subject for a moment, we can detect an inherent playfulness to their photographs; they are lovers exploring their surroundings. One photographic portrait from 1932 depicts Cahun washed up on the sand, rope tethering them to the ground, their limp body impersonating a swept-up siren. Just as Heroines and Disavowals enact multiple voices, Cahun takes on contradicting personas behind the camera lens; in a portrait from twelve years prior, they posed as a sailor, the victim of the siren’s enchanting song.

Cahun’s exploratory photography and prose, both of which conjure siren imagery, need to be read in dialogue. As the myth of the siren has been handed down through the centuries, it has an elevated literary status. Simultaneously, the siren embodies forbidden desires within the psyche. Therefore, the Surrealists understood just how effective the myth is for communicating a personal and political message. As Cahun appropriates the siren myth for altered ends, they thrash their metaphorical tail in an act of queer exploration; this is a uniquely different adaptation of the siren who was dismembered by Breton and trapped by Aragon.