Your currently viewing RAW Contemporary | View RAW Modern

Katalin Deutsch Blau, known as Kati Horna, was a Hungarian photographer who sought refuge from World War II in Mexico, where she met artists Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, joined the Surrealist group and documented her involvement in the arts, symbolism, and occultism.

While she is generally the less famous artist of the trio and mostly known for her portraits of Carrington and Varo, whose connection to magic and witchcraft is more immediate and easier to recognise, Horna had a long and important artistic career in Europe before joining the Surrealists in Mexico.

Born in Budapest in 1912, she studied photography with Robert Capa during her teenage years. The two developed a strong friendship which would go on to deeply influence her artistic practice and political beliefs. In 1933, they travelled to Paris together, where Horna began painting masks and dolls, giving her pictures a dreamy and surrealist feel. She and Capa remained close for more than twenty years, until his death.

She moved to Berlin in her early 20s where she met inspiring and important figures, such as playwright Bertolt Brecht and Bauhaus’ artist Moholy-Nagy. A few years later she returned to Budapest, where, during an apprenticeship with the photographer Jozsef Pecsi, her work and political beliefs became very radical . As a result of her activism in leftist organisations, she was convicted as an anarchist.

In 1937, Kati was sent to Spain by the Confédération Générale du Travail and the Popular Front to document the Civil War, and from there she also contributed to journals such as Mujeres Libres and Umbral. During this time, she chose to focus on the effects of the war rather than the battles on the front, documenting under-represented aspects of daily life, especially the suffering, pain and silence of the population.

Of Jewish origin, Horna eventually had to leave Europe with her husband José and never returned. In 1942, President Cardenas opened the Mexican borders to European refugees, and here she continued working with political journals (Mujer de Hoy, Mujeres, and Mapa..) and during this time her work definitively shifted from documentative to conceptual. In Colonia Roma in Mexico City, she met many fellow European artists who had also fled the war, such as Varo and Carrington. Among them, she found a strong community and artistic haven and would later be known along with Carrington and Varo as “las tres brujas”, the three witches. The three women often described themselves as a surrogate family and it is clear to us now that they deeply influenced each other’s lives and works.

An important aspect of this friendship was domesticity. Carrington and Varo notoriously experimented with native herbs and concoctions, studying alchemy, tarots, astrology, and pagan traditions. Horna might seem less directly connected to these themes at first, but her portraits of her friends reveal a strong fascination with different layers of reality: it has been written that Horna’s photographs were ‘less dependent on symbolism and more (grounded) in reality’, but to truly understand her works we need to consider what the Surrealist group defined as “reality” in the first place.

Horna’s portraits of her friends in the domestic sphere are reminiscent of the representations of witches from the early modern period (c.1500-1700): the kitchen became a place of female agency; the nursery became the setting of female intimacy and power; and the garden and nature became the scenarios of occult activities.

Through Horna’s pictures, we have access to her inner world, imagination, spiritual beliefs and practices as well as those of the artists she worked so closely with. Common themes of her work include witchcraft practices, the sacredness of motherhood and spiritual healing after the tragic experiences of the war. Her vocation has been best described as ‘(combining) a lucid vision of reality with (…) a creative reworking (…) of the drives of the unconscious’.

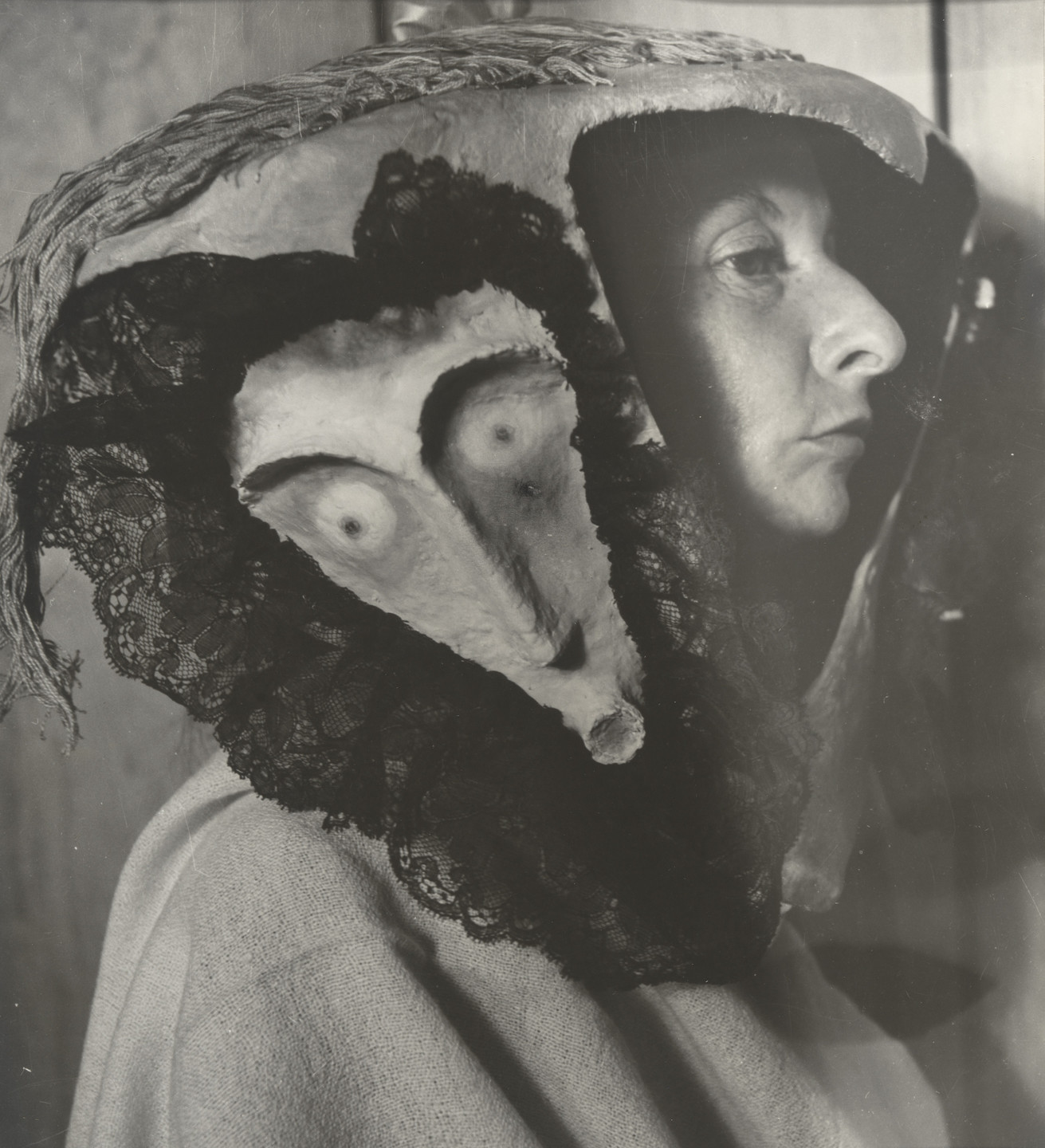

In the 1962 series “Ode to Necrophilia” for the avant-garde magazine S.NOB, Horna portrayed Carrington as the widow wearing a Mexican mantilla, a black lace veil, mourning her husband who is represented by a traditional white death mask on their unmade bed. The setting is sparse and while we clearly recognize it as a home, the atmosphere feels alienating. The grief, desire, and absence are an invisible reality that Horna materializes in the empty domestic setting, transporting the dead back into the real world, through Carrington’s sensations of physical longing.

The vast majority of Horna’s early work is believed lost due to the Spanish Civil War. She passed away in 2000.